The quiet remains of Cymer Abbey lie in a scenic valley on the edge of a shallow, bubbling stretch of the river Mawddach, which itself evokes tranquillity and peace. In spite of being approached via a caravan park, it is a truly idyllic spot. Cymer Abbey, Kymer deu dyfyr, meaning “meeting of the waters” and dedicated to the Virgin Mary was founded in 1198 and was one of the northernmost Cistercian abbeys in Wales.

An abbey consists of a church and monastery headed by an abbot and populated by monks. Because the monks were resident, usually for life, an abbey contains not merely the architectural components required for worship and contemplation, but the structures required for everyday living and self-improvement, including premises for cooking, eating, sleeping, meeting, learning and punishing. An abbey was designed to be self-sufficient, and therefore had an important economic component to support its religious and cultural endeavours.

The Cistercians

A 12th Century interpretation of St Benedict delivering his monastic rule in the 6th Century AD. Source: Wikipedia, via Monastery of St. Gilles, Nimes France (1129)

The Cistercian order of monks spread through Wales during the 12th Century AD. The European tradition of monastic living had a long heritage, based on the teachings of St Benedict of Monte Cassino in Italy in the 6th Century AD, who set down rules for monastic life, the standards to which subsequent Benedictine monastic orders adhered. As the monastic life spread through Europe, new orders were brought into being, most of them adaptations of the Benedictine rules, but modified to reflect their own ideologies and beliefs about how best to serve God. During the early Middle Ages, the Cistercians believed in devotion combined with hard work, an ethic at odds with the more opulent and self-indulgent Benedictine Cluniac order that was becoming dominant in France, and believed, unlike St Benedict himself, that hard work deterred from the celebration of God, and instead invested in ostentatious architecture decorated with stained glass windows, art works and precious metals, carrying out extensive and elaborate liturgical rituals, using music and song, as ways of glorifying god.

Johann Petr Molitor, Cistercian monks, murals in the Capitular Hall, Cistercian Abbey Osek, North Bohemia, before 1756. Source: Wikipedia, from the Cistercian Abbey of Osek, North Bohemia

The prosperous and comfortable Cluniac repelled many for whom the initial Benedictine vision was nearer to Christ. The Carthusians and Cistercians were both breakaway orders that sought to return to a more honest monastic life in which humility, obedience and hard work were combined with prayer and learning. Initially, the Cistercians embraced a much simpler way of life than contemporary orders, inspired directly by St Benedict and by the simple and sacrificial life described by Christ himself. They established their abbeys in very remote areas, isolated themselves from urban life, and from the associated temptations. Their undyed white tunics and cowls were an instant visual differentiator from the black tunics of other Benedictine orders, and lead to them being referred to as the White Monks. Different roles were assigned to different monks, such as the cellarer who controlled all food and drink for the entire abbey, the novice master, and the sacrist who was responsible for the upkeep of the church. All were were considered to be equal in status. The abbot was in overall charge of the monastery, and his orders were law, but he slept in the same dormitory as the other monks.

The monks worked the fields, engaged in building projects, and processed the harvest. They were assisted by lay brothers, uneducated and lower order members of the monastic community who ate, slept and worshipped in different places from the monks, and were not given access to certain parts of the abbey. Food was simple and plain. Meat was not consumed, and most of the protein consumed by monks came from beans, fish, eggs and cheese. Meat was banned by the Benedictines due to the dangers of its encouraging carnal passions, because monks were required to be celibate. The importance of fish in the diet, as well as the requirement for fresh drinking water, meant that many abbeys, like Cymer, were built near to rivers.

By the later Middle Ages, most of the stricter Cistercian rules were relaxed, and the abbot slept in his own quarters, sometimes a separate building altogether, the monks rarely worked the land themselves, and meat was consumed along with a much more elaborate selection of foodstuffs. The plagues of the 14th Century wiped out what remained of the lay brotherhood, and their work was carried out by servants.

The Welsh Cistercians

12th Century links between Cistercian monasteries. Source: Evans, D.H. Valle Crucis Abbey (Cadw). Although Citeaux, the node for all Cistercian abbeys, established early new bases in France, it was Clairvaux under the lead of St Bernard that was responsible for the earliest new abbeys in Wales. Of these Whitland was the most important for the northward spread of monasticism. The green lines emanating from Savigny reflect the Savignac order, which merged with the Cistercians after only 20 years, in 1147. So although Basingwerk in the north and Neath in the south were founded as Savignac orders, after 1147 they were brought under the rule of the Cistercians at Citeaux.

In southwest Wales, Whitland Abbey, which had been established from France in 1140, provided monks for new abbeys for the southwest of Wales, mid Wales, north Wales and southwest Ireland. A new abbey required an endowment by a donor, someone with enough land and wealth to give some of it away in return for the prayers offered by the monks for the souls of the donor and his family. Monks were considered to have a hotline to God. Having dedicated their lives to Him, and living sin-free lives, they built up a surplus of virtue and influence that could be employed on behalf of the living in order to provide for them in the afterlife, an intercession to minimize the impact of sins committed in life. Many early abbeys in England were sponsored by English royalty, but two distinct strands of monastic tradition were established in Wales after the Norman conquest.

In Wales, earlier versions of monasticism predated the Benedictines, but were much more modest in scope. The Benedictine version of monastic life, based on the model of the abbey, came to Wales in two movements. In southeast Wales, new abbeys were established in the wake of the Norman conquest and had a distinctly Anglo-Norman flavour. A second strand of monastic spread in Wales began at the Cistercian Whitland (Abaty Hendy-gwyn ar Daf) founded in 1140 by monks from St Bernard’s abbey at Clairvaux, second only to the Cistercians’ founding abbey at Citeaux. Whitland spawned a series of abbeys that were funded by the native Welsh princes and were populated almost exclusively by Welsh monks, a pura Wallia (Welsh Wales) version of Cistercian monasticism. By establishing new daughter abbeys under its authority, Whitland spread the Cistercian order into the poorer and more remote areas of Wales, where monks could practise their devotions in isolation but were still near enough to manors and villages to enable them to trade their produce, mainly agricultural, in exchange for the basics required for sustaining the abbey. Cymer, for example, traded its wool and horses to the court of Llewyllyn ap Gruffud.

Cymer Abbey

Although the foundation charter has been lost, it is known that Cymer was founded with an endowment by Maredudd ap Cynan, Lord of Merioneth, and possibly his brother Gruffudd ap Cynan. A charter of 1209, issued by Llewellyn ap Iorwerth, confirmed the grants and privileges of the abbey and validating its claims of ownership.

In the usual pattern, the first monks for the new abbey came from an existing abbey, in this case Cwmhir Abbey in mid Wales, itself founded from the mother house at Whitland in 1176. Other monks could then join from the local area, paying a single fee for their clothing, food and to begin their training as novices. The fee was not insubstantial, and although the monks took a vow of poverty, they were not themselves poor people before joining the abbey. As it happens, Cymer was one of the less economically viable of the Welsh abbeys and was therefore unable to support a large number of monks, and these monks would have lead a relatively impoverished lifestyle compared with those in wealthier Welsh abbeys like Strata Florida or Abbey Crucis.

Abbeys followed a standardized plan, with a cruciform church making up one side of a four-sided complex that surrounded a square section of grass or garden (the garth). Around the garth was a walkway, usually covered, called the cloister. This connected all the buildings, and also served as a processional way. Cymer differs from the standard layout in a number of ways.

Cadw site plan showing the surviving stonework in grey and brown, and the possible abbots lodging, as well as the missing section of the abbey

First, the abbey had both church and cloister, as well as the required buildings around the cloister, but the church as it survives today was not the standard cross-shaped arrangement. This is significant. Only the nave and the choir section, the piece that made up the long part of the cross has been found, even after 19th Century and more recent excavations. The nave was where the lay brethren prayed. Beyond a division across the nave to separate the public area from the private (the pulpitum), were usually the opposing transepts, two wings that made up the arms of the cross, with a tower built over the central section. Then, beyond this section, were the all-important choir and high altar where the most important rituals were enacted. These parts were exclusive to the monks, and provided access to the cloister and the upstairs dormitory. At Cymer the nave served the multiple role of nave, choir and chancel/sanctuary. The missing, exclusive section of the church (transepts, tower, choir and high altar) means either that this was destroyed in the past, or that it was never built. Most analysts favour the latter explanation, which suggests that the abbey was not endowed with a sufficient initial investment, and that its estates were not sufficiently profitable to enable the abbey to be built.

Normally, the church was the first building to be constructed in stone, with other accommodation built of wood until the church was complete, but at Cymer the ancillary buildings were built in stone even though the church was apparently incomplete, so it is all something of a puzzle. However, the small rectangle that made up the 13th Century church seems to have done the job of a larger entity, with the nave (reserved for the laity and visitors) at the west end, the monk’s choir in the middle, and the presbytery / chancel / sanctuary (the area around the high altar) at the end. The church was also divided into three sections length-ways by two aisles flanking the main central portion of the church (known as a basilica layout), achieved by adding columns and arches. At the business end of the church, where the monks worshipped eight times during the day and night, were some small decorative features, such as ornamental capitals at the top of columns. The main arch into the cloister was also slightly ornamental, and a tiny rose window topped the east end, but in keeping with Cistercian principles, there were few other ornamental flourishes, and although the abbey had a few pieces of fine silver ware, there would have been no stained glass, art works or tapestries.

At a later date, in the fourteenth century, it was quite clearly thought that a tower was a basic requirement and that its absence was a detriment, so a small tower was added (shown on the above plan in brown). Bizarrely, however, it was added at the wrong end. The church was usually orientated west to east, the entrance at the west and the choir and high altar at the east. The tower sat between east and west ends, at the point where the arms of the cross intersected with the main run of the church. The new tower, however, was put at the west end where the main entrance from the outside world would have been positioned. It was small and understated in terms of its overall dimensions, but its walls were immensely thick. It was provided with corner buttresses and was clearly built to last.

The cloister appears to have followed the standard Cistercian format. The most important room was the Chapter House, which was on the east side of the cloister. Here, every day for around 15-30 minutes, the monks sat on benches along the walls to hear the abbot, who sat on a raised platform, read a chapter from the rules of the order, and to discuss the upcoming business of the day. Confessions were made and punishments decided upon. Next to the Chapter House was often a book cupboard, where important religious texts and treatises were kept, and in some abbeys copied for wider distribution. Between the Chapter House and the church was usually a sacristy, which held the vestments and other essentials for the daily liturgies that took place in the church. At the other end of the Chapter House was the day room, a heated room where monks could seek respite in the cold winter months.

Above this east range of rooms was usually the monks’ dormitory and latrines. Although the abbot would have slept with the monks in the early years, by the 15th Century at Cymer he had his own house, over the site of which a farmhouse now stands. Against the cloister wall shared with the church were often desks to enable reading and copying. At the far end of the cloister, opposite the church, was the refectory. At some abbeys this is perpendicular to the line of the cloister, sticking out, but at Cymer it lies along the cloister. A stone lavatorium (washing trough or bowl) would have been close by, often in the garth, and monks ritually purified their hands with water before eating. It is not clear what made up the west range, but it could have included, for example, the kitchen, the cellarer’s office and the lay brothers’ day room and refectory.

Cistercian abbeys were known for their skills diverting and using water. At Cymer a v-shaped channel drew water off the river and diverted it through the refectory. It still flows today.

The monastery was never one of the Cistercians’ more successful establishments. In fact, it was probably one of the most understated and impoverished of the abbeys. Most of the successful abbeys supported themselves by farming, selling wool from herds of sheep, horse breeding, tithes (a special tax on householders that supported church establishments), by taking income from estates that they owned, and by personal donations. Its contemporary, Valle Crucis near Llangollen, founded in 1201, benefitted from all of these sources of income, but Cymer was always a very modest outpost of the Cistercian world. Cymer lacked the big grange estates that supported Valle Crucis, had little agricultural land and few fishing rights, although it did sell its wool and horses to the prince Llewellyn ap Iorwerth (died 1240). Most of its properties were in mountainous areas, including Llanelltyd, Llanfachreth, Llanegryn and Neigwl on the Lleyn peinsula. Dairying seems to have been a primary activity, and Llewellyn’s charter mentions metallurgy and mining, which is surprising for such a small establishment. Cistercian abbeys all owned loyalty to the founding abbey in France, Citeaux. Cash was clearly short. Every year abbots were required to visit Citeaux to participate in the General Chapter, a vast gathering of abbots and other monastic leaders that served to ensure obedience to the order and to reinforce its rules. In 1274, the abbot of Cymer had to borrow a sum of £12.00 (today about 8,757, the equivalent of 15 horses or 34 cows) from Llewellyn ap Gruffud (died c.1282) to enable him to undertake the expense of the journey.

There were multiple difficulties establishing an abbot who could be trusted to run the abbey, and these resulted in disputes that would not have helped the fortunes of the abbey:

In 1443, John ap Rhys left office at Cymer and appeared as an abbot in Strata Florida Abbey. In his place a John Cobbe was chosen, but Rhys did not think to give up Cymer and banished his successor. This led to the taking of the convent and his new abbot Richard Kirby under royal custody. Once again, the monarch’s supervision was necessary in 1453. During this period, the abbey’s income was valued at a very small amount of £ 15 of annual income. Despite the royal interventions, disputes over the appointment of the abbot’s office continued at the end of the 15th century. In 1487, there was even excommunication by the general chapter of one of the monks, William, because of his self-proclaimed election. Despite this, in 1491 he was again mentioned in the documents as abbot of Cymer. Lewis ap Thomas was the last superior of the monastery since 1517. [from Janusz Michalew’s Ancient and Medieval Architecture]

The entrance from the south aisle of the church into the cloister. Only monks were permitted to use this.

It is also clear that Cymer suffered during military conflicts, which cannot have helped its fortunes. Some of its buildings were burned during one of Henry III’s campaigns. Llewellyn ap Gruffud made the monastery his military headquarters in both 1275 and 1279, and only a few years later Edward I occupied the abbey in 1284. There are records that Edward paid £80.00 compensation to Cymer for damages inflicted during the occupation. Today this is equivalent to £55,525 (around 94 horses or 177 heads of cattle). By 1379 only an abbot and four monks were resident at the abbey. In Henry VIII’s 1536 evaluation of the value of abbeys, the abbey was valued at only £51 13s and 4d (around £6,913 today, enough to purchase 3 horses or 12 cows). [Currency conversions from the National Archives Currency Convertor].

In the early 16th Century Henry VIII had fallen out with the Pope over his wished-for divorce from Catherine of Aragon. As the head of the church in England and Wales, Pope

Clement VII was the only person who could rubber stamp the divorce. Henry was fortunate that the Protestant movement started by Luther was taking shape in Europe, and in order to remove himself from the power of the Pope, he aligned himself with the new movement and declared himself the head of the Church of England. No longer owing any loyalty to Catholic institutions, he set out to value them as economic units, a survey called the Valor Ecclesiasticus, and in 1536 announced that any abbeys with an income less than £200.00 should be “suppressed” under the Act of Suppression. This effectively meant that they were closed as monastic establishments, their valuables sold or melted down. Some villages took over the church, whilst some were given or leased to new owners. The grandeur of some of the abbeys proved to be very attractive to some new owners. If abandoned, the lead used in roofs and drainage stripped, leaving them vulnerable to the weather. As a small abbey, Cymer was a victim of this first round of suppressions, and was closed in 1536/37. Other, much larger and prestigious abbeys were disbanded over the following years.

Although Christianity and spiritual concerns were still important in both urban and village life, there does not appear to have been much public resistance to the closure of abbeys. The central role of monasteries in caring for the souls of the rich had gone into decline, but the abbeys were still important parts of economic and social life, engaging in trade, dispensing charity, caring for the sick and welcoming pilgrims. It was still considered to be good to have all that spirituality on one’s doorstep. Still, the rumblings generated by Martin Luther, whose views on all the liturgies, prayers and rituals that took place in abbeys were soon well known (he referred to them as “dumb ceremonies”), and his comments on the Catholic fixation on saints and relics as “mere superstition,” were finding attentive audiences throughout Europe. In fact, the world was becoming rather less superstitious as time went on and knowledge began to supplement if not replace faith. The world in which the monasteries operated was changing, and Henry VIII gave the world a far from subtle push in a completely new direction.

Although some abbots and priors stood up for their institutions against the Act of Suppression, that was always, in practical if not spiritual terms, a mistake – they were usually killed and their establishments destroyed. In the north of England a 30,000-strong protest descended on York demanding that their monasteries remained open. Henry VIII promised that the grievances of the protestors would be heard if they would return to their homes, but 200 people regarded as central to the protest were rounded up and killed.

Other religious leaders and their followers, either due to fear or pragmatism, counted their blessings and accepted the radical change if not happily, at least without active resistance. Some abbots and priors jumped on Henry’s bandwagon and went to work elsewhere in the new church structure, whilst the remainder of the individuals in the monastic community, male and female, were pensioned off. The immense wealth that Henry amassed with the sudden acquisition of the abbeys, their lands and their treasures was eventually spent on wars.

At the east end of the abbey, in the south aisle, an arched recess is provided with touches of decorative red sandstone. These touches give an idea of how the abbey achieved some degree of ornamentation without the opulence of cathedrals and Cluniac abbeys.

Apparently someone, possibly the abbot, attempted to save some of the abbey’s dignity (or secure himself a nice pension) by hiding Cymer’s ecclesiastical plate, consisting of a 13th Century silver gilt chalice and paten, under a stone at Cwm-y-Mynach. Whatever the motive, whether to return it to the abbey’s headquarters at Citeaux, or to melt it down for personal benefit, it was never retrieved. Like most of the portable heritage of North Wales, it found its way to the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. I have been unable to find out if it is still there, or to find an image of it.

Following dissolution, the property was leased to John Powes, “royal servant,” but not until May 1558. It was probably robbed for building stone for surrounding farm buildings and dry-stone walling, and once the roof either fell into disrepair or was robbed for tiles or lead, exposure would have led to rapid deterioration.

Spiral staircase in the 14th Century tower leading to – where? There was presumably an upper floor in the tower.

Visiting

Cymer Abbey is easy to reach. It lies just off the A487 north of Dolgellau and is well sign-posted. After driving through a small caravan park, there are two very attractive farm buildings, and a small parking area. Both parking and access to the abbey ruins are free of charge. There is an information board showing the main features of the abbey.

Cymer Abbey is easy to reach. It lies just off the A487 north of Dolgellau and is well sign-posted. After driving through a small caravan park, there are two very attractive farm buildings, and a small parking area. Both parking and access to the abbey ruins are free of charge. There is an information board showing the main features of the abbey.

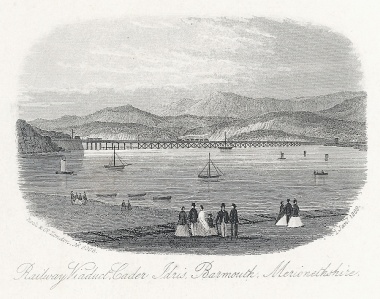

The river Mawddach, which was a ford during Medieval times, had a lovely road bridge built over it in the 18th Century, which is now a foot bridge. A car park on the Cymer side of Llanelltyd bridge is provided for those walking to the New Precipice Walk above the village of Llanelltyd on the other side of the bridge. The views from the bridge, both over the river and over the surrounding countryside, are well worth adding to the abbey visit. The bridge could do with a bit of maintenance, as the roots from the shrubs embedded into its brickwork will start to pull the mortar out and undermine the structure of the bridge.

The river Mawddach, which was a ford during Medieval times, had a lovely road bridge built over it in the 18th Century, which is now a foot bridge. A car park on the Cymer side of Llanelltyd bridge is provided for those walking to the New Precipice Walk above the village of Llanelltyd on the other side of the bridge. The views from the bridge, both over the river and over the surrounding countryside, are well worth adding to the abbey visit. The bridge could do with a bit of maintenance, as the roots from the shrubs embedded into its brickwork will start to pull the mortar out and undermine the structure of the bridge.

Sources:

Books and papers

Burton, J. 1994. Monastic and Religious Orders in Britain 1000-1300. Cambridge Medieval Textbooks. Cambridge University Press.

Burton, J. and Kerr, J. 2011. The Cistercians in the Middle Ages. Boydell Press

Davis, S.J. 2018. Monasticism. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press

Evans D.H. 2008, Valle Crucis Abbey, Cadw 2008

Gascoigne, B. 2003 (2nd edition). A Brief History of Christianity. Robinson

Gies, F. and Gies, J. 1990. Life in a Medieval Village. Harper

Gilingham, J, and Griffiths, R.A. 1984, 2000. Medieval Britain. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press

Krüger, K. (ed.) 2012. Monasteries and Monastic Orders. 2000 years of Christian Art and Culture. H.F. Ullmann.

Livingstone, E.A. 2006 (Revised 2nd edition). Concise Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press

Robinson, D.M. 1995 (2nd edition). Cymer Abbey. Cadw

Robinson, D.M and Harrison, S. 2006. Cistercian Cloisters in England and Wales Part I: Essay. Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 159:1, p.131-207

Websites

Coflein

Cymer Abbey

https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/95420?term=cymer%20abbey

Ancient and Medieval Architecture – by Janusz Michalew

Llanelltyd – Cymer Abbey

https://medievalheritage.eu/en/main-page/heritage/wales/llanelltyd-cymer-abbey/

English Heritage

The Dissolution

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/dissolution/

Monastic Wales

Cymer Abbey

https://www.monasticwales.org/browsedb.php?func=showsite&siteID=27

Open Yale Courses (Yale University, Connecticut)

The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000 (course given by Professor Paul H. Freedman)

https://oyc.yale.edu/history/hist-210