Introduction

I will be talking about shipping, shipbuilders and individual ships over the next weeks and months, and in order to put these topics into context, I have been looking at how a maritime tradition developed not merely in Aberdovey but in west Wales as a whole. The following summary, amalgamating information in a number of secondary resources, is brief but hopefully provides sufficient information to introduce shipping and shipbuilding in the Aberdovey area. For those who would like to read more, I have listed the books and papers I used at the end of the post.

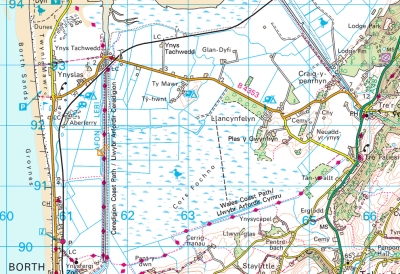

Mid-West Wales showing the locations of Aberdyfi (or Aberdovey), Tywyn, Borth, Machynlleth, Aberystwyth, Corris and Barmouth, key places in the story of coastal and deep sea trade and boat- and shipbuilding. Google Maps.

The 900-mile Welsh coastline, includes many river estuaries and natural harbours. Mid Wales sits within Cardigan Bay, a sweeping arc at the east of the Irish Sea, extending from the Llyn peninsula in the north to St David’s peninsula in the south. As Moelwyn Williams says: “the small ports and creeks along the coastline were focal points in the economic life of the Welsh people: they formed a kind of network of commerce and trade.” Often largely cut off from the interior due to the absence of roads, and excluded from land-based trade networks, it may have seemed inevitable that the Welsh coastal inhabitants would take to the sea, but in fact up until the 18th Century the vast majority of the ships exporting Welsh goods and supplying Welsh ports with Welsh, Irish and English goods were either English or Irish.

The Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages natural harbours became important for provisioning of military bases established by foreign invaders to fend off attempts to oust them. This means that most shipping engaged in trade at that time was not Welsh but Norman. J. Geraint Jenkins describes how wine and fruit imports could come from as far away as France and Spain, giving the example of Edward III who gave Tenby a grant to build its first landing stage in 1328, enabling it to import wine from France. Wales in return exported agricultural produce, animal hides and wool. Other traders came from nearer to home, particularly from ports along the Bristol Channel, exchanging a wide variety of imports in return for agricultural produce. An important fishing industry also developed during the Middle Ages, taking advantage of the rich herring shoals, both for local consumption and, salted, for export. The salt for preserving the herring was imported from Ireland, Cheshire and Lancashire. Irish vessels carried most of the salted fish for export, and most other ships came not from Wales but ports like Liverpool and Deeside. Piracy and smuggling were both common, with Irish salt the most commonly smuggled import due to its importance for preserving fish for export and the high duty imposed on it since 1693. Smuggling of salt only ceased when the duty was dropped in 1825.

The 17th and 18th Centuries

After the conflicts of the Middle Ages a wide range of commodities and industrial products were transported along the coastline. As J. Geraint Jenkins says “Much Welsh export was transported in the veritable armada of ships owned by local people who traded the entire length of the Welsh coast.” This highlights two important points. Ships were owned by local people, sometimes by individuals who owned only one ship, usually by locals who combined their resources to purchase shares in a ship, and only more rarely by ship owners who could afford more than one ship, sometimes extending to a small fleet. The second point is that whilst much of the trade was local, in the sense that it was focused on moving commodities from one part of Wales to another, an eternal revolving door of commercial activity, some ships were also travelling regularly to Ireland and Europe, exchanging local Welsh products like wood, wool, coal, fish, wheat and beer for commodities like wine, different agricultural produce, fruit and kitchen wares.

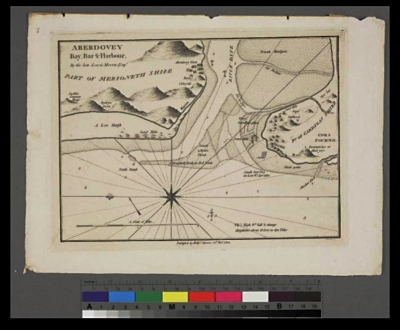

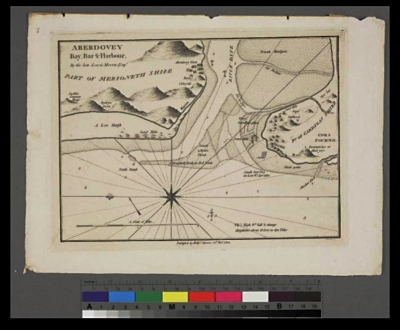

Map of Aberdovey and its harbour in 1801. By William Morris and Lewis Morris. (National Library of Wales. Used under terms of license)

In the 18th Century, Wales was swept into the Industrial Revolution and goods like lime, coal, granite, bricks, slate, tin, lead and copper joined the export trade, and it seems to have been this that gave Welsh coastal inhabitants the impetus to take to the sea. As these new materials acquired increasing importance, so did the Welsh coastline, with investment both into improvements at existing ports, harbours and wharves and into new ports to serve specific industries. At the same time, small flat-bottomed boats continued to land on beaches to unload their cargoes, requiring no specialized facilities. Passengers, too, increasingly required transportation between commercial centres. Coastal work dominated, but long distance trade also continued to have an important role, not merely to Europe but across the Atlantic and elsewhere, facilitated by both local and foreign shipbuilders who were now building the larger ships required for such enterprises. Moelwyn Williams says that by 1768 there were around 60 ports and cargo handling creeks in Wales from Chepstow in the south to Chester in the north. In the early days of its maritime tradition, many sailors were also engaged in land-based trades, spreading the risk. By the 19th Century, however, sailors were engaged in the maritime trade full time.

The 19th Century

The High Street of Cardigan in 1855 by Joseph Clougher (Source: National Library of Wales. Used under license)

It was only in the 19th Century that Welsh ports developed into more prosperous and organized enterprises, hubs for longer distance and sometimes international trade, building on the 18th Century trades and reinforcing it with new produce. Exports included slate, lead, copper, oak poles and planks, wooden furniture, bark, trenails (wooden pegs), butter, cheese, wheat, malt animal hides, dried salmon and wool were exported. Williams says that imports included goods from Liverpool, including bricks, tiles, boards, fir timber, potatoes, turnips and clover seeds as well as foreign commodities such as tea, sugar, tobacco, raisins, Spanish wines and spirits. Competition opened up between ports, both under sail and under steam, as trans-Atlantic trade and passenger travel took off. Steam began to make its presence felt in Wales from the first half of the 19th Century, but as Williams and Armstrong discuss, sail still dominanted for heavy cargoes, partly because steamers were most appropriate for rivers and lakes rather than the open sea, fuel costs for carrying the heavy industrial cargoes were prohibitive, and they were unsuitable for bulk cargoes due to the size of the coal bunkers that they carried. For most of the 19th Century sail and steam worked together in harmony, each suitable for different roles. Competition with the railways, spreading remorselessly into even the most remotest parts of England, Scotland and Wales, undermined coastal shipping, but provided some ship owners with the motivation to engage in more ambitious trading enterprises in the long distance deep sea trades. These ships were usually not based in Wales, and did not export Welsh goods, but many of them were owned by Welsh individuals and companies who were themselves based in Welsh villages and many were crewed by Welsh sailors. Local shipbuilders now had to compete with the Canadian counterparts for business. Many of the big ships owned in Wales were built by famous clipper and schooner shipbuilders in Canada used to designing ships that could tackle the dreadful conditions around Cape Horn. Both American and Canadian ships were larger than most British ships. In spite of the benefits of size and short-term durability, they were built of softwoods, which had a much shorter lifespan than the durable hardwoods preferred by British shipbuilders. Welsh sailors were soon to be found on ships travelling all over the world on ships that could be away from Britain for many months at a time, travelling west from ports like Liverpool, London, Bristol and Cardiff to Europe, New York, round Cape Horn to Peru and California and east as far as China, Japan and Australia. The main exports from Wales were slate and coal, with ships returning from Canada with salted dried cod for the Mediterranean, from America with copper ore, from Peru with guano, from Chile with copper ore, from the China and Japan with tea, from Australia with wool, from the Mediterranean with wine, oil, fruit, iron ore and zinc, and from eastern Europe with grain for western Europe and timber for Britain. All destined for the major British ports including Liverpool, London, Newcastle, Bristol and Cardiff. Iron ore and copper ore were of particular importance to south Wales where the tin and steel trades were developing towards the end of the 19th Century.

Cardiff became the biggest port in Wales and in the north Holyhead on Anglesey was dominant due to its connections with Ireland. In mid-west Wales Cardigan was an important port until the late 18th Century, when Aberystwyth, which had started to become a successful port during the late 18th Century began to overtake it. Liverpool dominated west coast trade in the northwest. There were many attempts to establish mid-Wales terminals for either crossing between Britain and Ireland, or as bases for trans-Atlantic passenger liners. Porthmadog, on the northwest Welsh coast, became important due to the demand for slate in the early 19th Century. Unlike Cardigan, which grew up over the centuries, it was the brainchild of William Maddocks who in 1810 created a sea wall and diverted a river in order to reclaim land for agricultural use, which led to the river carving out a natural harbour at Porthmadog, making it an ideal location for exporting slate. Four narrow gauge railways descended into the town, which became an important port and an important shipbuilding centre, producing famous schooners.

Shipbuilding was a natural match for a country with an important export trade and a poor inland transport infrastructure. As trade grew, so did the demand for new ships, the men to sail them, and all the crafts associated with the shipbuilding industry. Wood and metalworking, rope-making, sail-making, anchor manufacture, mast-makers and other craft specialists, all provided work for local craftsmen who benefited from the business. Building wooden sailing ships was surprisingly low-tech. It did not require, for example, the construction of dry docks or the provision of cranes. All that was needed was a flat piece of land, preferably a beach or close by, the supply of timber, particularly oak, a saw pit and something to act as a mould loft (a sort of design studio) where the ship plan is laid out, and and men with the requisite skills to create scaffolding, work wood and finish a ship. Porthmadog was famous for its beautiful schooners, but a lot of other Welsh ports produced ships, including most notably Barmouth and Pwllheli, and the river Dyfi was a smaller base for shipbuilding at Aberdovey, Penhelig, Morben and Derwenlas. Some of the vessels produced were small sailing ships, with no more than one mast, like sloops, smacks, snows and ketches, but many were more ambitious including two-masted schooners such as the 84 ton 75ft Frances Poole, the 112 ton 83ft Acorn and the Jane Owens, both built by John Jones of Aberdovey, brigantines such as the 148 ton 88ft Charlotte built in Barmouth for Aberdovey owner Thomas Daniel, and square rigged brigs, including the substantial two-masted 208 ton 101ft Rowland Evans, built at Derwenlas and even three-masted barques like the Mary Evans. The bigger ships, particularly the square-rigged ships, travelled all over the world, as demonstrated by Alan Jones’s description of the career of John Jenkins, born and raised in Borth in the 1800s, who sailed on several Aberdovey-built ships. Churches and chapels for different denominations grew up, support services for locals and visitors developed and an entire social infrastructure, including schools, pubs, hotels, shops and ferry services evolved to serve the needs of these growing communities. Local railways serving quarries and mines improved the connection between industries and ports and even the roads eventually improved.

Ships were financed by local investors, each of whom owned one or more of 64 shares. These included the ship’s captain, farmers, quarry owners, merchants and similar businessmen with who had need of ships for their own business ventures, as well as craftsmen who worked on the ships, the ship’s and ordinary people from the local community who saw them as an opportunity for profit or to expand meagre incomes. When larger enterprises developed with two or more ships, the most common model for ship ownership was the Single Ship Company, in which the manager or owner takes a portion of the gross earnings of the ship rather than a share of its profits, thereby benefiting from its successes without suffering from its losses. An alternative with the Limited Joint Stock Company, an innovation of the 19th Century in which an individual could invest in a company without risking his personal fortune.

As steam began to replace sail on all but the most remote parts of the globe, where steamers were unable to carry sufficient coal for the long legs between coaling stations, the Welsh shipbuilding industry began to go into decline. The Welsh coastal ports never invested in the development of a steam shipbuilding industry, and the shipbuilding industry died out when steam largely replaced sail during the late 19th Century. With a busy coastal trade based on steam, Welsh boys and men continued to go to sea, in spite of low salaries and uncomfortable conditions, finding it a viable alternative to work available in small farming communities and the hinterland beyond. Even with the advance of rail, much of west Wales still offered limited opportunities for young men who did not want to work on the land or leave to find work in other areas. Jenkins says that in the big ports, steamship owners “preferred sailors from rural Wales because they know how to handle a ship in difficult situations on a rugged coastline” and that on many ships sailing from Cardiff, Welsh was the first language.

Shipping and Shipbuilding in Aberdovey

Aberdovey was located in the Ynysymaengwyn estate, in the parish of Tywyn, at the far south of Meirionnydd (formerly Merionethshire). It is a good example of a small fishing village, specializing in herring, that grew into a small but important port as its own natural resources became desirable elsewhere. Lewis Lloyd, in his admirable book “A Real Little Seaport” (1996), describes how, in its hey-day “Aberdyfi was a great deal more than a coasting port with a modest fleet of locally built smacks and schooners . . . . Aberdyfi possessed a number of deep-water or ocean-going vessels which sailed to distant places and Aberdfyi’s larger schooners, especially those built at Aberdyfi by Thomas Richards, sailed to St John’s Newfoundland, and to Labrador along with Porthmadog’s famous 3-masted schooners. . . Aberdyfi was, in short, a complete and diversified small port.” Aberdovey started from modest beginnings, and there are almost no traces of its shipbuilding and shipping past now, but it is still possible, via the work of a number of authors, to trace the history of Aberdovey and to locate some of the long-buried centres of activity on the ground today.

Williams says that the first official reference to Aberdovey as a port was in 1565, coming to life only during the herring season, when it was described as “a wonderful great resort of fishers assembled from all places within this Realm with Shippes, Boats and Vessells.” Just two years later, however, the official port books show that a substantial amount of cargo was being offloaded at Aberdovey, and the same records show that lead ore was the chief export. By the end of the 16th Century Aberdovey was a busy maritime location. Aberdovey became both the region’s registry throughout the 16th and 17th Centuries, and it was the most important herring port in Cardigan Bay. Herring fishing took place in autumn and winter, and during the spring and summer the same vessels engaged in carrying coastal cargoes. A Custom House had been established from at least the 17th Century, and J. Geraint Jenkins quotes a 1704 report from a local newspaper quoted by Jenkins that says that customs officers from the Aberdovey office caught three boats smuggling salt that was ready to be loaded on horses, around 200 of them, In New Quay.

Aberdovey in 1834 (National Library of Wales. Used under terms of license)

A significant source of work for Aberdovey came from its with Derwenlas. Derwenlas, at the last navigable point on the River Dyfi, was the major port serving Machylleth, a thriving wool manufacturing centre based on the unnavigable part of the Dyfi, 2 miles inland from Derwenlas. Industries like the 17th Century silver mill and Royal Mint at Furnace (Ffwrnais) and the subsequent lead smelting furnace on the same site in the 18th Century depended on the sea to send and receive cargoes. Sea vessels were too large to navigate the river Dfyi, and river vessels were too small to tackle coastal waters, so all cargoes were trans-shipped at Aberdovey, making the port a hub for local trade. Furnace is the subject of another post on this blog. Machynlleth’s position at the meeting point of Montgomeryshire, Cardiganshire and Merionethshire at the border between north and south Wales was significant, and provided Aberdovey, as the main port for the Dyfi valley and beyond with, as Lewis Lloyd puts it, a certain “hybrid vigour.” In 1770 the Custom House moved to Aberystwyth, taking with it some of Aberdovey’s status, but not its business. In 1776 a bigger blow was the establishment of the statutory registers of shipping, in which Aberdyfi was subordinate to Aberystwyth, which firmly established Aberystwyth as the dominant port in mid Wales.

In the 19th Century trade expanded and Aberdovey the relationship between Derwenlas and Aberdovey continued to be symbiotic, whilst Aberdovey began to develop in its own right. Slate exports became Aberdovey’s main source of income from at least the 1850s, with other cargoes supplementing this trade. Williams gives details of the cargo shipped down the river for export including slates, bark and timber, whilst imports included rye, wheat, limestone, and English and foreign hides. Most of the area’s wool exports went out from Barmouth. Jenkins describes how Corris slate was conveyed via tramway to Derwenlas and lead ore was was brought from Dylife in horse and cart. Samuel Lewis, writing in 1883, adds that tree bark, oak timber and oak pole for collieries were also loaded into river boats at Derwenlas. Imports offloaded at Derwenlas included rye, wheat, coal, culm (a form of coal), limestone, hides and shop goods including groceries. All products into and out of Derwenlas had to be carried by river, so Aberdovey functioned as the major hub for transferring cargoes to and from river boats to and from seagoing ships. Even cargoes destined for Aberystwyth from America were often trans-shipped at Aberdovey into barges from the 1840s, because Aberystwth’s harbour was too shallow to handle the the big deep-drafted trans-Atlantic vessels. In 1852 a marine insurance society was formed in Aberystwyth, but Aberdovey never formed one, which, as Lloyd points out, underlines the secondary nature of Aberdovey at this time.

The largest ship ever built on the Dyfi, at Derwenlas, the 258-ton barque The Mary Evans built by John Evans in 1867 (Source: Dyfi Osprey Project on Faceook at https://bit.ly/2N9YecU)

Shipbuilding took place all along the river Dyfi, at Aberdovey, Penhelig, Aberleri, Morben Isaf (now a caravan park) and Derwenlas. D.W. Morgan says that in the mid 19th Century around fifty five schooners were built on the Dyfi, as well as a barque, two brigantines, three brigs and fourteen sloops. Some of these larger ships were specifically built to serve the trans-Atlantic trade, where size and speed were in demand for carrying woollen goods. The best known of the shipbuilders was Thomas Richards who built ships in Aberdovey. Ship’s crews came from the the parish of Tywyn, the Dyfi valley and its hinterland, with a remarkable number coming from Borth, on the other side of the river in Ceredigion, at that time Cardiganshire.

In the 1860s the railway connected Machynlleth and Aberystwyth, undermining Derwenlas, and the construction of a railway bridge to extend it up the coast cut off traffic upriver. The railway arrived in Aberdovey in 1867, marking an end to the shipbuilding yard at Penhelig, which was already suffering from competition from experienced shipbuilders in the north-east and Canada. Jenkins says that the last ship to be built on the Dyfi was the 1869 76-ton 75.2ft schooner/ketch Catherine built at Pennal. It had been the same story in Borth, across the estuary, and Barmouth to the north. In both cases, when the Aberystwyth and Welsh Coast Railway arrived in the 1860s maritime trade went into decline and together with the shipbuilding industry. This was just a year before the last sailing ship, the 1870 794-ton tea clipper Lothair, was built at Rotherhithe on the Thames, demonstrating that although the new Dyfi railway bridge, the west coast railway itself and Canadian-built ships were challenges to shipbuilding and maritime trade in the Aberdovey area, there was a bigger threat.

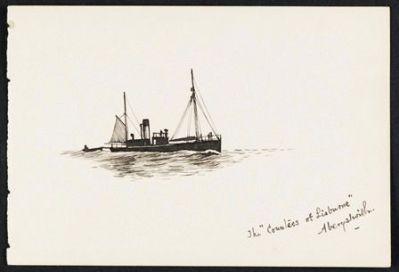

Steam power was slowly taking over the sea, and many steamships and long distance sailing ships were now iron-hulled. Whilst some shipyards on the Thames began to make steamers, Wales never got to grips with building steamships, an industry that became concentrated in north-east England and, most importantly, in Scotland on the Clyde. Steam, however, held out considerable hope for the future prosperity of Aberdovey, capitalizing on the proximity of Aberdovey to the Midlands and improving trade links along the coast. In 1834 the Cardigan Bay Steam Navigation Company began to provide a service between Aberystwyth and Pwllheli with the S.S. Vale of Clwyd, stopping at Barmouth, Aberdovey, Aberaeron and New Quay. It carried passengers in the summer but also carried cargo in the winter, including livestock, and agricultural produce. In 1880 the Waterford and Aberdovey Steamship Company was established to connect the Midlands to Ireland for carrying livestock and passengers, but this was short-lived. In 1892 the Aberdovey and Barmouth Steamship Company Ltd., financed mainly by Liverpool wholesale grocers,.sailed most weeks between Liverpool and Aberystwyth with three ships, the S.S. Countess of Lisburne, the S.S. Dora and the S.S. Grosvenor.

The decline in maritime trade was not the end of Aberdovey’s prosperity in the short term. Slate was carried on the Talyllyn railway into Tywyn, where it was trans-shipped to Aberdovey and then loaded on to the mainline railway.

Crowds at the Aberdovey wharf at a regatta in c.1885. (National Library of Wales. Used under terms of license)

In the 1880s the slate trade went into a slump, but in 1882 new wharves, animal pens and warehouses were built, handling imports of timber, corn, livestock and fuel for distribution both locally and throughout Britain, and it continued to handle diminished exports of local slate and agricultural produce. As steam took over from sail, the character of the town changed. Although hopes of becoming a port between Ireland and the Midlands was sustained for some time, these were doomed to failure because Holyhead in the north and first Neyland and then Fishguard in the south dominated shipping across the Irish Sea, both thanks to excellent rail connections with London. Sadly, hopes of a trans-Atlantic steamer service also came to nothing. Trade, like shipbuilding, began to suffer in the late 19th Century, in spite of the railway. Jenkins describes how the lead and slate industries went into decline and the wool trade came to a close. Timber continued to be imported, and the Melin Adrdudwy steam flour roller mill continued to be productive in the late 19th Century, but by 1914 the main form of income was tourism.

Future posts will look at some of the above topics in more detail, with reference to specific examples from Aberdovey and the surrounding area.

References

The main sources for this post are as follows, with full details listed in the Bibliography:

Fenton, R. 1989

Gwynedd Archaeological Trust 2007

Jenkins, J.G. 2006

Jones, A. 2010

Lewis, S. 1833

Lloyd, L. 1996, volume 1

Morgan, D.W. 1948

Williams, D.M. and Armstrong, J. 2010

Williams, M. I. 1973

The Salt Association website