On a lovely day, quite unprecedented for February, I decided to go a bit further afield than my usual strolls on Aberdovey beach and go to Ynyslas. I had been meaning to go for a long time.

On a lovely day, quite unprecedented for February, I decided to go a bit further afield than my usual strolls on Aberdovey beach and go to Ynyslas. I had been meaning to go for a long time.

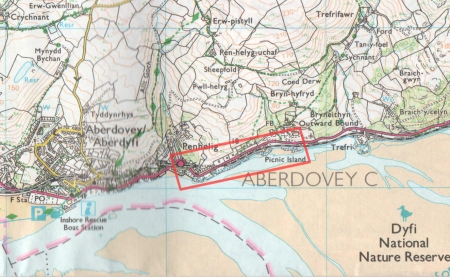

Ynyslas carries with it the novelty of parking on the beach. There is a nominal fee when the visitor centre is open (from Easter to the end of September), but it is free in the winter months when the visitor centre is closed. The drive to Ynyslas from Aberdovey takes about 40 minutes via Machynlleth, and of course you are driving in a loop around the Dyfi estuary because Ynyslas is immediately opposite Aberdovey. There used to be a passenger ferry between the two, which had been operated for centuries, but eventually became redundant when the railway was built and the roads improved to handle the growing number of cars.

Visitor Centre, Ynyslas

Ynyslas is a nature reserve, properly entitled the Dyfi National Nature Reserve and Visitor Centre and as well as the sand dunes and the beach, includes the Cors Fochno raised peat bog, which is of international importance. I have only been to Ynyslas once before, and then only very briefly when it was an exploratory mission tacked on to a visit to the terrific mill at Furnace (covered on a previous post). The visitor centre was open then, and had stacks of books on tables for visitors to consult, information boards, and a good collection of relevant books, greetings cards and small toys to buy, as well as a coffee and tea machine. Considerate to out of season visitors there is a big board outside, by the entrance, showing the layout of the nature reserve, with the paths clearly marked.

Out of season Ynyslas is virtually empty of bodies, just a few dog walkers in the dunes and rather more on the beach. I decided to do the circular walk that leads through the dunes, out on to a stretch of beach, and then back along the mouth of the estuary to the car. The dunes are of particular interest because they demonstrate all the stages of dune formation and growth, and there are multiple types including both fixed and mobile dunes. There was not a lot to see other than marran grass at this time of year, but come the spring there will be all sorts of flowering plants and insects to see including wild orchids, mosses, liverworts, fungi, insects and spiders.

Out of season Ynyslas is virtually empty of bodies, just a few dog walkers in the dunes and rather more on the beach. I decided to do the circular walk that leads through the dunes, out on to a stretch of beach, and then back along the mouth of the estuary to the car. The dunes are of particular interest because they demonstrate all the stages of dune formation and growth, and there are multiple types including both fixed and mobile dunes. There was not a lot to see other than marran grass at this time of year, but come the spring there will be all sorts of flowering plants and insects to see including wild orchids, mosses, liverworts, fungi, insects and spiders.

Fringe of pebbles between the dunes and the beach at Ynyslas

Where the path tips you out on the beach there is a big ribbon of huge rounded grey pebbles that lies between you and the vast, eternal vistas of sand. You need to be a bit careful as they shift constantly underfoot. Once safely installed on the beach there is tons to see, and it is quite different from the stretch between Tywyn and Aberdovey. For one thing, there is a sense that you can see forever down the beach along Cardigan Bay. It is a very wide, open stretch of beach, with the waves chasing each other up the sand in long white-topped lines for as far as the eye can see.

Ynyslas beach (click to enlarge)

Before the beach reaches the estuary, the sand is largely uninterrupted by the mass of small cockle, razor clam and tellin shells that scrunch underfoot on the stretches on the north side of the estuary. Instead, there are occasional shells of a completely different character, and even the usual species like cockles are generally much larger. Gigantic Icelandic cyprine and common otter shells are dotted around, big common whelks are a frequent sight and the pod razor clams reach their maximum lengths along this section of beach. Of the smaller species the limpets were a pleasant surprise, as were needle whelks and acorn barnacles. Some of the shells contained keelworm tubes (spirobranchus). In the sand itself there were dozen upon dozen of sandhopper burrows. I was surprised at how many articulated bivalves I found, both halves still connected, including well preserved cockles

Before the beach reaches the estuary, the sand is largely uninterrupted by the mass of small cockle, razor clam and tellin shells that scrunch underfoot on the stretches on the north side of the estuary. Instead, there are occasional shells of a completely different character, and even the usual species like cockles are generally much larger. Gigantic Icelandic cyprine and common otter shells are dotted around, big common whelks are a frequent sight and the pod razor clams reach their maximum lengths along this section of beach. Of the smaller species the limpets were a pleasant surprise, as were needle whelks and acorn barnacles. Some of the shells contained keelworm tubes (spirobranchus). In the sand itself there were dozen upon dozen of sandhopper burrows. I was surprised at how many articulated bivalves I found, both halves still connected, including well preserved cockles

The Icelandic cyprine (Artica islandica, also known as the ocean quahog) is particularly fascinating. It has a dark brown periostratacum (outer skin of a shell) and lives so long that it is amongst the longest living of any animal – up to 500 years. Amazing to think that an Icelandic cyprine shell could have contained a creature that was alive when Shakespeare was writing. The oldest known, its age determined by counting growth rings, was 507, and was nicknamed Hafrún (c. 1499–2006) . This example is 10cm (4 inches) from top to bottom.

The Icelandic cyprine (Artica islandica, also known as the ocean quahog) is particularly fascinating. It has a dark brown periostratacum (outer skin of a shell) and lives so long that it is amongst the longest living of any animal – up to 500 years. Amazing to think that an Icelandic cyprine shell could have contained a creature that was alive when Shakespeare was writing. The oldest known, its age determined by counting growth rings, was 507, and was nicknamed Hafrún (c. 1499–2006) . This example is 10cm (4 inches) from top to bottom.

Dog whelks (Nucella lapillus), which are lovely to look at and beautifully constructed along a spiral axis, are actually somewhat stomach-churning in their feeding habits. Like all gastropods, whelks have a toothed tongue called a radula. They use it to drill through the shells of other gastropod, and produce a chemical to help with the process. Once the shell has been pierced, they inject other chemicals into the shell cavity to paralyze and liquefy their prey before extracting it through the hold in the shell. You can spot the holes in shells on the strandline.

Dog whelks (Nucella lapillus), which are lovely to look at and beautifully constructed along a spiral axis, are actually somewhat stomach-churning in their feeding habits. Like all gastropods, whelks have a toothed tongue called a radula. They use it to drill through the shells of other gastropod, and produce a chemical to help with the process. Once the shell has been pierced, they inject other chemicals into the shell cavity to paralyze and liquefy their prey before extracting it through the hold in the shell. You can spot the holes in shells on the strandline.

One of the whelks had keelworm (Spirobranchus) tubes. These calcareous tubes are made by the keel worm with an open and closed end. The open end allows it to put out tentacles with which it feeds on organic detritus, whilst safely armoured in its shell. Like keelworm tubes, barnacle shells are also found on shells of other organisms. There were several examples of acorn barnacles at Ynyslas, like the dog whelk in the above photograph, all in clusters because barnacles form colonies.

Sandhopper burrows (click to enlarge)

Sandhoppers (Talitrus salafor) are interesting too. At around 20mm in length, they look rather like fleas, with their backs arched. They live in burrows at depths up to 30cm and emerge at night to feed on the strandlines. Although they live on the strandline they are terrestrial and cannot survive in the water so when the tide comes in they dive into their burrows, backfilling with sand to plug the passage and protect themselves. They are targeted by some species of wading birds.

I found two nursehound eggcases, which I dutifully reported to the Shark Trust. One of them was partially covered with what look like tiny shells, as well as some keelworm tubes. I thought at first that the shells might the blue-rayed limpet (Patella pellucidum) but quite apart from the fact that they are the wrong shape, I cannot see any of the radiating blue lines that ought to be present if this identification were correct. Perhaps they are very early on in the growth cycle.

I found two nursehound eggcases, which I dutifully reported to the Shark Trust. One of them was partially covered with what look like tiny shells, as well as some keelworm tubes. I thought at first that the shells might the blue-rayed limpet (Patella pellucidum) but quite apart from the fact that they are the wrong shape, I cannot see any of the radiating blue lines that ought to be present if this identification were correct. Perhaps they are very early on in the growth cycle.

The limpets are common in some areas, but I have never seen one at Aberdovey. There were plenty on the beach at Ynyslas. Like dog whelks they have a toothed radula, but they infinitely more friendly to other species. They feed on algal spores left behind when the tide recedes, and in clearing patches of seaweed they create opportunities for other species to colonize rocks, increasing biodiversity along the seashore.

Ducks

As I returned towards the car I thought I could hear oyster catchers, but all I could see were ducks. If you are a refugee from an urban environment, like me, you might associate ducks with the coarse quacking of mallards, but these sounded more like oyster catchers, with a a high-pitched peeping noise as you can hear in the video. They were feeding in the marsh grasses in the muddy zone at the edge of the estuary waters.

The views from Ynyslas towards Aberdovey, as you round the corner from the open sea into the estuary, are breathtaking, particularly on a gloriously sunny day. Beyond the town you can see down the Dyfi, a long peaceful arc of water flanked by low hills.

Aberdovey from Ynyslas

The BBC website has a good suggested walk beginning at Ynyslas, which goes further than I did and can take up to three hours. The Natural Resources Wales website gives more information about what to see at Ynyslas, and it offers a number of suggested walks of different durations. I plan to return to do the Cors Fochno walk, and to do another dune walk when there will be plants in flower.

I drove past the golf course into Borth for a quick stroll along the seafront, overlooking the pebble beach and rolling waves. Now a seaside town, it used to be the main source of sailors for the local shipping trade in the 19th Century.

Borth

After a walk along the Dysynni last week, I did a three point turn by the footbridge and drove back along the line of the railway. Instead of turning left to head back towards Tywyn I decided to turn right over the level crossing and park up to see if I could reproduce the picture from the Cardigan Bay Visitor that I posted last week. Unfortunately for that plan I had reckoned without the addition of a caravan park since the original illustration was drawn, and both the railway track and the village were completely hidden behind it. On the other hand, the beach at low tide was a complete revelation.

After a walk along the Dysynni last week, I did a three point turn by the footbridge and drove back along the line of the railway. Instead of turning left to head back towards Tywyn I decided to turn right over the level crossing and park up to see if I could reproduce the picture from the Cardigan Bay Visitor that I posted last week. Unfortunately for that plan I had reckoned without the addition of a caravan park since the original illustration was drawn, and both the railway track and the village were completely hidden behind it. On the other hand, the beach at low tide was a complete revelation. This part of Tywyn is apparently called Sandilands, but is something of a misnomer. There is certainly sand on the beach, but mostly it is a mixture of fine and coarse gravel, surprisingly harsh on the feet, with some swathes of pebbles around, all divided by wooden breakers. I had never seen it at low tide, and was amazed to see that the sloping beach ended in huge green-topped rocks and lovely weed-filled rock pools with sand between them, with an enormous stretch of wide open sea on the other side. The sea was splendid, with lovely white-topped waves chasing each other in, crashing on the rocks and pebbles and sounding just what a seaside should sound like.

This part of Tywyn is apparently called Sandilands, but is something of a misnomer. There is certainly sand on the beach, but mostly it is a mixture of fine and coarse gravel, surprisingly harsh on the feet, with some swathes of pebbles around, all divided by wooden breakers. I had never seen it at low tide, and was amazed to see that the sloping beach ended in huge green-topped rocks and lovely weed-filled rock pools with sand between them, with an enormous stretch of wide open sea on the other side. The sea was splendid, with lovely white-topped waves chasing each other in, crashing on the rocks and pebbles and sounding just what a seaside should sound like. There were quite a few people around, most large family/friend groups, but not so many that social distancing was a problem, and it was all terribly civilized. I had really enjoyed having the Tonfanau beach all to myself, but it was also splendid to see people of all ages launching themselves into the waves and having a really great time. The caravan park overlooking the beach takes the edge off the beauty of the place, but keep your eyes facing seawards and there is nothing to disappoint.

There were quite a few people around, most large family/friend groups, but not so many that social distancing was a problem, and it was all terribly civilized. I had really enjoyed having the Tonfanau beach all to myself, but it was also splendid to see people of all ages launching themselves into the waves and having a really great time. The caravan park overlooking the beach takes the edge off the beauty of the place, but keep your eyes facing seawards and there is nothing to disappoint. I was intrigued by what looked like huge boulders made of coral. When I stooped to touch one, it was clear that these rock-like structures were made of sand, and consisted of fine walls dividing thousands of tiny tunnels. The beach is full of them, and they are really very lovely. After a rumble round the web I found that they are Honeycomb worm (Sabellaria alveolata) colonies. The reef structures resemble honeycomb. The colonies form on hard substrates and they need sand and shell fragments for tube-building activities. They manufacture the tubes from mucus to glue the tiny pieces together. When the tide is out the worms retreat deep into the tunnels, but when the tide covers their reefs their heads protrude and they feed on micro-organisms in the water, including plankton.

I was intrigued by what looked like huge boulders made of coral. When I stooped to touch one, it was clear that these rock-like structures were made of sand, and consisted of fine walls dividing thousands of tiny tunnels. The beach is full of them, and they are really very lovely. After a rumble round the web I found that they are Honeycomb worm (Sabellaria alveolata) colonies. The reef structures resemble honeycomb. The colonies form on hard substrates and they need sand and shell fragments for tube-building activities. They manufacture the tubes from mucus to glue the tiny pieces together. When the tide is out the worms retreat deep into the tunnels, but when the tide covers their reefs their heads protrude and they feed on micro-organisms in the water, including plankton. Because there are rock pools, it is possible to see various seaweeds in their natural habitat floating freely in the clear water, a lovely kaleidoscope of colour. In the pools themselves there were lots of tiny fish, which can be seen in the video. On the actual rocks (rather than the honecomb worm reefs) there were limpets, barnacles and various sea snails, none of which we have in Aberdovey due to the lack of rocks. Of course there are none of the shells that Aberdovey’s beach has in such profusion, because they get broken up on the rocks and pebbles but, together with the pebble beach at Tonfanau, it’s super that there are three such contrasting beaches such a short distance apart.

Because there are rock pools, it is possible to see various seaweeds in their natural habitat floating freely in the clear water, a lovely kaleidoscope of colour. In the pools themselves there were lots of tiny fish, which can be seen in the video. On the actual rocks (rather than the honecomb worm reefs) there were limpets, barnacles and various sea snails, none of which we have in Aberdovey due to the lack of rocks. Of course there are none of the shells that Aberdovey’s beach has in such profusion, because they get broken up on the rocks and pebbles but, together with the pebble beach at Tonfanau, it’s super that there are three such contrasting beaches such a short distance apart. I had a lovely long paddle, and would have loved to have had a swim, but even if I had gone in with my denim shorts and t-shirt, I had no way of drying myself off. Next time for sure, and I’ll start to keep a towel in the car!

I had a lovely long paddle, and would have loved to have had a swim, but even if I had gone in with my denim shorts and t-shirt, I had no way of drying myself off. Next time for sure, and I’ll start to keep a towel in the car!