Vintage postcard of Aberdovey showing both sail and steam in port.

The local shipbuilding industry, which started on the back of the Industrial Revolution in around 1840, didn’t survive the arrival of the railway, partly because the upper reaches of the river Dyfi were cut off, but also because wooden sailing ships for deep-sea cargo carriage were being built more cheaply and ambitiously in Canada whilst, most conspicuously, steamships were beginning to replace sail all round the coast and across the oceans. Early 19th Century steamship services had developed along big rivers and estuaries like the Thames and Clyde, with corresponding shipbuilding services fulfilling a real demand. These were populous areas in need of reliable passenger and cargo transport and a number of entrepreneurs found that there was a good market for pleasure trips. In Wales, these early steamers were too expensive to run for low-margin cargoes and were not suitable for carrying heavy goods. As the technology improved, so did the ships. There were many advantages of steam over sail. Steamers could set sail in all weathers and tides, they could operate to a timetable, and those built of iron could be much larger than wooden equivalents.

The Dovey Belle. Source: Lewis 1996, plate following p.120

By the mid 19th Century a number of Welsh shipbuilders had tried their hand at steam, including the 1854 Victoria built in Barmouth and the single Aberdovey-made steamer, Aberllefeni Quarry Maid, launched in 1858 (see below), usually known simply as Quarrymaid. This experiment did not evolve into a steamboat industry either in Aberdovey or Barmouth, where another steamship had been built. The development of a shipbuilding industry in Wales, for even small steamers, was inhibited for a number of reasons. These included the expense of dredging access routes for the building of bigger ships, adapting shipyards, adding new infrastructure and acquiring new skills. The last Aberdovey ship was launched from Penhelig in 1880, the schooner Olive Branch, a pattern of shipbuilding decline that was echoed in small ports along the Welsh coast as the shipbuilding industry came to a standstill. The last Dovey-built ship to frequent Aberdovey was the 1867 84-ton schooner Dovey Belle, which met her end in 1907.

The Aberdovey jetty, fitted with rails

Towards the end of the 19th Century, steamships from other areas visited small Welsh coastal ports, and Aberdovey continued to be an active port until the First World War. The earliest steamships were paddle steamers, successfully crossing the Atlantic on regular crossings between Britain and America, and these were succeeded later by the much more efficient screw (propeller) steamers. In 1887 a new Aberdovey jetty was built, 370ft long. Approached along a pier, it enabled ships to load and unload at both low and high tide, encouraging the visits of steamships. The pier and jetty were fitted with railway tracks and a turntable, so that the main railway could be connected directly with shipping via the Aberdovey Harbour branch.

The only steamer to be built in Aberdovey was the 83.1ft long above-mentioned Aberllefeni Quarry Maid, built by Roger Lewis to serve as a coastal vessel, and was launched in October 1858. She was fitted out with two De Winton 50hp engines and associated machinery in Caernarfon, and undertook her maiden voyage from Aberdovey to London in April 1859, with several of the owners on board, some of whom disembarked at Aberystwyth. Her normal route was between Aberdovey and Liverpool, averaging a round trip per fortnight, but one one occasion she was chartered for a pleasure cruise to Aberystwyth and back, as reported in the North Wales Chronicle and Advertiser on 3rd September 1869.

ABERDOVEY.—On Thursday the Steamer Quarrymaid from Aberdovey took a trip as far as Aberystwyth and back. The weather was beautifully fine, and a rich treat was thus afforded. About eighty from Towyn and Aberdovey, visitors, &c., availed themselves of a trip, H. Webster, Esq,, of Aberdovey bore the expenses of the excursion, to whom great praise is due for his kindness and liberality at all times in Aberdovey and vicinity. During the passage, singing was kept up with spirit. After spending about six hours in Aberystwyth, the Quarrymaid steamed off at about nine knots an hour, and Aberdovey was reached in good time. Three hearty good cheers for Mr. Webster was given on board, which was joined in by the multitude on shore, who greeted the company on their return. A private company was entertained by the same gentleman at the Hotel, and a pleasant evening spent.

ABERDOVEY.—On Thursday the Steamer Quarrymaid from Aberdovey took a trip as far as Aberystwyth and back. The weather was beautifully fine, and a rich treat was thus afforded. About eighty from Towyn and Aberdovey, visitors, &c., availed themselves of a trip, H. Webster, Esq,, of Aberdovey bore the expenses of the excursion, to whom great praise is due for his kindness and liberality at all times in Aberdovey and vicinity. During the passage, singing was kept up with spirit. After spending about six hours in Aberystwyth, the Quarrymaid steamed off at about nine knots an hour, and Aberdovey was reached in good time. Three hearty good cheers for Mr. Webster was given on board, which was joined in by the multitude on shore, who greeted the company on their return. A private company was entertained by the same gentleman at the Hotel, and a pleasant evening spent.

In 1862 she had a six-man crew. It is not known when she went out of service. If anyone knows of a photograph, please get in touch!

The paddle steamer Vale of Clwyd. Source: National Museum of Wales (via Williams and Armstrong 2010)

As far as I can tell, the earliest visiting steamers to arrive in Aberdovey were those of the Cardigan Bay Steam Navigation Co. It was formed in 1834 by local gentry and operated a summer service from Pwllheli to Aberystwyth with their one funnelled, two-masted paddle steamer, the 60hp p.s. Vale of Clwyd (p.s. standing for paddle steamer), commanded by John Hughes of Pwllheli. She left Pwlheli every other day and returned on alternative days, but did not run on Sundays. Her round trip between Aberystwyth and Pwllheli included stops at Barmouth and Aberdovey, both on outgoing and return trips. There’s no record of how she was received in Aberdovey, but a local newspaper reported that on her arrival in Aberystwyth, she was greeted by “nearly all the population of the town and country for several miles around.” Later in the same year she also stopped at Aberaeron and New Quay. On 27th May 1934 the North Wales Chronicle warmly greeted the linkage of Aberystwyth and Pwllelli, seeing it as a solution to opening up the Welsh coast “so long hermetically sealed against tourists and travellers.” It seems to have been a short-lived service, and the ship was moved to the Portdinllaen to Liverpool route the following year.

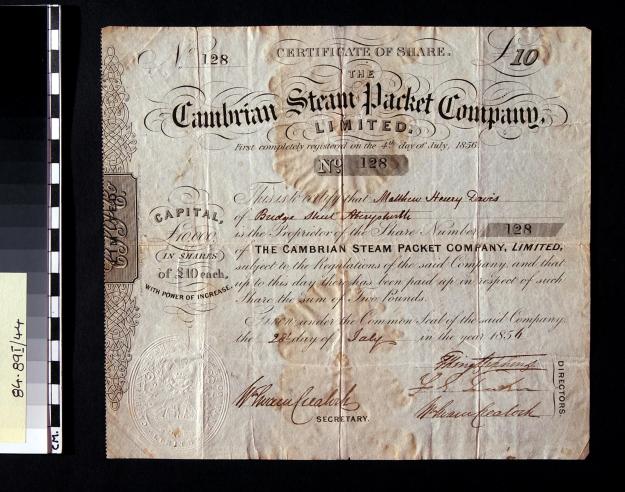

The next steamers to stop at Aberdovey were owned by the Cambrian Steam Packet Co, which was registered as the Cambrian Screw Steamship Co Ltd in March 1956, but changed its name In April.

The company operated out of Aberystwyth, with ships going to Bristol, Liverpool and London and extended the service to Swansea. It carried both cargo and passengers to these destinations, stopping off at intervening smaller ports, including Barmouth, Tywyn, Aberdovey, New Quay, Aberaeron, and Aberystwyth. The earliest advert I have found dates to 1859, singing the praises of the ship Plymlymon. An 1859 Cambrian Steam Packet Company advert in the first edition of the Aberystwyth Observer has an illustration of the ship Plymlymon, captained by William Wraight, which carried goods and passengers between Liverpool, Aberystwyth and Bristol, stopping at Holyhead, Portmadoc, Aberdovey, Aberaron and New Quay. Although prioritizing cargo, the advert goes on to say “Excellent accommodation for Passengers. Stewardess on board.” Fares from Liverpool and Bristol to Aberystwyth, Portmadoc, Aberayron, Aberdovey, Cardigan and New Quay cabins were 12 shillings and steerage 7 shillings. Between either Aberystwyth, Aberaeron, Aberdovey, Cardigan, new Quay, Portmadoc or Holyhead, cabins were 9 shillings and steerage was 6 shillings. The full advert is shown at the end of this page. The appearance of the advert in 1888 is somewhat confusing, as the Cambrian Steam Packet Company is said by a number of sources to have closed in 1876, so I am looking for more information on the subject. Later ships advertised were Aberystwyth, Queen of the Isles, Young England, Genova and Liverpool, all steamships. In 1863 an additional steamer, Cricket, was added to the list of ships running on this route “with Liverpool, Bristol and London goods,” and “good accommodation and a stewardess on board.” Although it ran cargo and offered passenger less expensive prices than the railway, it found competition from the combination of rail and the establishment in 1863 of a rival steamship company difficult, and folded in 1876.

In the absence of a picture of Elizabeth, here’s a photograph of her owner Thomas Savin instead. Source: Wikipedia

The Cambrian Railway was directly responsible for the arrival of the paddle steamer p.s. Elizabeth in 1863 from Blackwall, London (please get in touch if you know of a photo). In the early 1860s, during the construction of the Cambrian Railway that began in 1862 (discussed further here), Elizabeth was purchased to serve as a ferry. The Cambrian’s railway engineer was contractor Thomas Savin (about whom more on the aforementioned post about the railway). Savin had originally intended to build a bridge across the Dyfi to connect Aberdovey and Ynyslas by rail, and this remained the plan for some time, but due to the local geomorphology, civil engineers decided that the bridge could not be built and an additional 12 miles of rail had to be laid to go around the estuary, crossing the river just north of Gogarth instead. This meant that until the new stretch was built, southbound passengers had to cross the river by ferry between Aberdovey and Penrhyn Point, just beyond Ynyslas, linking the railway, where a line had been built. Savin himself purchased Elizabeth, a 30 horse-power Blackwall (London) paddle steamer that was also rigged for sail as a backup for the engines. According to a report in the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald she arrived at Aberdovey in 8am, having sheltered in Milton Haven for a number of nights, on the morning of 10th October 1863. She was captained by a Machynlleth resident Captain Edward Bell, who was succeeded by his younger brother Captain John Bell. She had a draft of 20 inches (i.e. she was shallow beneath the waterline) and was “fitted up like a yacht.” Unfortunately Elizabeth was not a success, as a letter printed in the 7th November 1863 edition of the Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald makes clear. Although elegant, with “much the resemblance of the Great Eastern build,” she was “almost totally useless as a means of conveyance.” At c.125ft long she was too long “by a third of her present length,” meaning that small boats had to take up the slack, as they had done before the arrival of the steamship. He goes on: “A trip of two or three times a weeks is all ‘our toy’ can make, and she has neaped [grounded] on a sand bank since Monday last!” In the same edition, it was reported that piers were under construction for the ferry at Aberdovey on one side of the estuary, and Penrhyn on the other, which seems like something of an afterthought!

Steam train making its way along the estuary towards Machynlleth, after the completion of the Aberdovey to Aberystwyth section of the line, eliminating the need for a ferry.

When the railway was eventually completed in 1867 it ran along the Dyfi Estuary, routing through the outskirts of Machynlleth and down the coast to Aberystwyth, making the ferry redundant. Savin sold Elizabeth in 1869 to an agent in Londonderry. Long after the railway was complete, sleepers were still brought into the port for the Cambrian Line. The Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald notes the arrival of the steamers Lizzie (which belonged to Lewis and Co of Mostyn) in September 1889 and Lotus in July 1891 loaded with sleepers. This evidently continued at least as late as 1908 when the residents of Bodfar Terrace and Glandovey Terrace joined forces to present a petition to the Cambrian Railway co. asking for the removal of the piles of sleepers stacked in front of their houses, “as they are a great eyesore to visitors and residents.” They were particularly concerned that they should be taken away before the influx of August visitors.

Lizzie. Source: Fenton 1989b, p.121

The Aberystwyth and Cardigan Bay Steam Packet Company was formed by seven shareholders from Aberystwyth, including the harbour master, a master mariner, two merchants, two grocers and a carrier. It was probably founded in 1863.

The Countess of Lisburne. Source: National Museum of Wales

The first ship purchased, in 1857, was the 108 ton s.s. Express, followed by the 118 ton s.s. Henry E. Taylor (built for the company by Bowdler, Chaffer and Co, Secombe) in 1868 and the s.s. Grosvenor (built by Crabtree and Co, Great Yarmouth later on (s.s stands for screw steamer or steamship). The service ran between Aberystwyth and Liverpool, stopping off at ports along the way, including Aberdovey. The business was reconstituted twice and in 1885 became the Aberystwyth and Aberdovey Steam Packet Company, to raise new operating funds of £4,000 (none of which came from Aberdovey). At this time the Henry E. Taylor was transferred briefly to new company. It was sold a year later when the 135 ton Countess of Lisburne (above) was purchased. She was in turn replaced in 1908 by the steel 219 ton Grosvenor (shown below), which sailed to Liverpool on a weekly basis. She was sold in 1916. It is clear from the 1908 AGM, reported in Cambrain News and Merionethshire Standard on 7th May 1909, that the business was suffering from ship outages due to repairs and other difficulties with the ships. I have quoted it an length, although the entire report is longer (see it here) but I think it is worth it for the insights that it offers into the operational difficulties:

The balance sheet had been prepared and the accounts audited by Messrs. Graham King and Co. who regretted to report a large adverse balance as the result of the Company’s trading for the year an unsatisfactory result which seemed to be entirely attributable to the breaking down of the old steamer. During the time that boat was on offer for sale and temporarily laid up for repair it was necessary to hire another steamer in order to retain freights and good will. That hiring cost the Company £450. There was also a serious loss in freight for the year, there being a de- crease of £512 in the gross earnings. The sale of the old steamer resulted in a capital loss of £1,266 I8s Id., which the auditors suggested should be wiped off over a period of ten years and had therefore charged the past year’s profit and loss account with £126 13s. 9d. The new steamer had been running about two months in the period covered by the accounts and it was trusted that the increased carrying capacity in the present- year would show a good profit, especially as the working expenses were practically the same as in the smaller boat. The report of the directors was as follows :—Your directors, in presenting the annexed balance sheet and profit and loss account for the year ended 31st December, 1908, regret to state that there is a net loss for the twelve months of £478 6s. 2d. It will be observed that a sum of£228 19s. 6d. was expended on repairs to the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne,” and a sum of £430 was paid for the^hire of another steamer during the time the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne” was on offer for sale and temporarily laid up for repair, in order as far as possible to retain the freight and goodwill. There was a considerable falling off in the traffic during the negotiations for the sale of the s.s. Countess of Lisburne,” as the steamer chartered by your Company, having to call at other ports. was not able to meet the requirements of the freighters at this port, and this accounts for the decrease in the gross earnings during the year. It is hoped that all this will now be obviated as the s.s. “Grosvenor” has a carrying capacity of 250 tons, as against the 120 tons of the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne.” and the attention of the shareholders is called to the fact that the working expenses of the s.s. Grosvenor” will be about the same as those of the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne,” with the great advantage of having a carrying capacity of 130 tons more than the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne.” It is hoped that all the shareholders will assist the directors and officials in developing the trade of the steamer, so as to wipe off the existing loss and that the directors may be in a position to declare a dividend before the end of the coming year.

The balance sheet had been prepared and the accounts audited by Messrs. Graham King and Co. who regretted to report a large adverse balance as the result of the Company’s trading for the year an unsatisfactory result which seemed to be entirely attributable to the breaking down of the old steamer. During the time that boat was on offer for sale and temporarily laid up for repair it was necessary to hire another steamer in order to retain freights and good will. That hiring cost the Company £450. There was also a serious loss in freight for the year, there being a de- crease of £512 in the gross earnings. The sale of the old steamer resulted in a capital loss of £1,266 I8s Id., which the auditors suggested should be wiped off over a period of ten years and had therefore charged the past year’s profit and loss account with £126 13s. 9d. The new steamer had been running about two months in the period covered by the accounts and it was trusted that the increased carrying capacity in the present- year would show a good profit, especially as the working expenses were practically the same as in the smaller boat. The report of the directors was as follows :—Your directors, in presenting the annexed balance sheet and profit and loss account for the year ended 31st December, 1908, regret to state that there is a net loss for the twelve months of £478 6s. 2d. It will be observed that a sum of£228 19s. 6d. was expended on repairs to the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne,” and a sum of £430 was paid for the^hire of another steamer during the time the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne” was on offer for sale and temporarily laid up for repair, in order as far as possible to retain the freight and goodwill. There was a considerable falling off in the traffic during the negotiations for the sale of the s.s. Countess of Lisburne,” as the steamer chartered by your Company, having to call at other ports. was not able to meet the requirements of the freighters at this port, and this accounts for the decrease in the gross earnings during the year. It is hoped that all this will now be obviated as the s.s. “Grosvenor” has a carrying capacity of 250 tons, as against the 120 tons of the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne.” and the attention of the shareholders is called to the fact that the working expenses of the s.s. Grosvenor” will be about the same as those of the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne,” with the great advantage of having a carrying capacity of 130 tons more than the s.s. “Countess of Lisburne.” It is hoped that all the shareholders will assist the directors and officials in developing the trade of the steamer, so as to wipe off the existing loss and that the directors may be in a position to declare a dividend before the end of the coming year.

Countess of Lisburne. Source: Fenton 1989b, p.41

The Grosvenor was operated by the Aberystwyth and Steam Packet Co from 1908 until 1916. This photograph shows her after she had been sold. Source: Maritime Wales by John Richards, p.111

Seaflower. Source: Fenton 1989b, p.21

The Cardigan Steam Navigation Company, which was registered in 1869 to run cargo between Cardigan, Bristol and Liverpool and other ports that seemed viable at the time. I have not seen any reference to its ship Tivyside stopping in Aberdovey, but it seems probable that they did stop, if only occasionally. In 1888 it went into liquidation, having failed to survive competition with the Cardigan Commercial Steam Packet Co., established in 1876 with the ship Seaflower (built by J. Reid and Co, Port Glasgow). This itself ran into trouble when Seaflower ran into the wooden sailing brigantine Charlotte in November 1879, resulting in damages of £1200. This finished the company, but a new company was created in the same name, with the same ship. This endured until 1902, closing down shortly after replacing Seaflower with the Mayflower.

In 1874 a Royal Navy survey was carried out in the River Dyfi to reduce the incidence of accidents, the result of which was a new sailing chart. Although I cannot track down a name for her, this lovely paddle steamer is, according to Hugh M. Lewis in Pages of Time, the Royal Navy’s survey ship. She has a single funnel and two masts with schooner rigging. Two large rowing boats are on the aft deck, and two smaller tenders (ship-to-shore boats) float at the steamer’s side. I love the ornamental paddle cover and the washing hanging out to dry.

In 1874 a Royal Navy survey was carried out in the River Dyfi to reduce the incidence of accidents, the result of which was a new sailing chart. Although I cannot track down a name for her, this lovely paddle steamer is, according to Hugh M. Lewis in Pages of Time, the Royal Navy’s survey ship. She has a single funnel and two masts with schooner rigging. Two large rowing boats are on the aft deck, and two smaller tenders (ship-to-shore boats) float at the steamer’s side. I love the ornamental paddle cover and the washing hanging out to dry.

Advert for the Waterford and Aberdovey Steamship Co. Source: Hugh M. Lewis Portraits of a Village. Lewis does not state the name of the newspaper in which the advert was placed.

In 1887 a line from Aberdovey to Waterford (and other ports) in southern Ireland was established, the Waterford and Aberdovey Steamship Company, to be subsidized by rebates, after some difficulty, by the Cambrian Railway. A report in Cambrian News said that “a valuable connection has been formed with Ireland, and traffic is brought upon the railway that otherwise would not have reached it. The first ship in the service was the 246 ton s.s. Liverpool, which ran a livestock transportation service from April 1887 from Waterford to Aberdovey. On her first trip she brought a general mixed cargo together with 60 pigs, returning with another general cargo to Waterford. She made four such trips in that April, and records show that another ship, Magnetic, made more than 12 trips from Waterford to Aberdovey between November 1887 and March 1988. Departures from Waterford had to be timed carefully to coincide with the Aberdovey tides. Livestock pens were built at Aberdovey for holding incoming cattle, pigs and horses, prior to their transportation by rail to other parts of Britain, particularly the Midlands. Livestock was a potentially good cargo for shipping, assuming that the demand was there. Not only were there few handling costs (livestock was simply led or herded off a ship into waiting pens, with minimal manpower and no lifting gear required) but it was thought that there would be demand in urban areas. An advert in Hugh M. Lewis Portrait of a Village (page 64), and dated July 1888, is shown to the left, advertising both its electric lighting, which was also in its cattle holds, and its superior passenger accommodation. Another 1888 advert below advertises “Great acceleration of transit” on the steamers s.s. Magnetic (and possibly s.s. Electric), “Carrying passengers, Merchandise and Live Stock in connection with the Cambrian Railways, at Low Through Rates, the principal English and Welsh Towns”. An interesting paragraph towards the end of the advert details the following advantages:

“For the conveyance of Live Stock from Ireland, owing to the favourable course of the currents in the part of the Channel to be navigated, and its freedom from fogs. On arrival at Aberdovey shippers may, as suits their convenience, either despatch their Stock to destination immediately by Special Trains, or place them in a large field adjoining the Cambrian Company’s Station, where they will be allowed to remain free of charge for twenty-four hours, and from which they can be loaded at any time direct into Trucks. Another advert in Lewis’s book, dating to later in 1888 reads: “Shortest and most expeditious route to Lancashire, Yorkshire, Midland Counties etc. Sailings for August and September 1888. The s.s ‘Magnetic‘ is a fast boat, and is fitted throughout (including the cattle space) with the Electric Light. The Passenger Accommodation is of a superior description. A Steward and Stewardess on board.”

“For the conveyance of Live Stock from Ireland, owing to the favourable course of the currents in the part of the Channel to be navigated, and its freedom from fogs. On arrival at Aberdovey shippers may, as suits their convenience, either despatch their Stock to destination immediately by Special Trains, or place them in a large field adjoining the Cambrian Company’s Station, where they will be allowed to remain free of charge for twenty-four hours, and from which they can be loaded at any time direct into Trucks. Another advert in Lewis’s book, dating to later in 1888 reads: “Shortest and most expeditious route to Lancashire, Yorkshire, Midland Counties etc. Sailings for August and September 1888. The s.s ‘Magnetic‘ is a fast boat, and is fitted throughout (including the cattle space) with the Electric Light. The Passenger Accommodation is of a superior description. A Steward and Stewardess on board.”

Lewis Lloyd lists some of the livestock carried by Magnetic, the dates showing when dues were paid on each cargo (1996, p.219) including the following example:

- 8/11/1887: 14 cattle,

- 15/11: 7 cattle and 233 pigs

- 20/11: 212 cattle, 187 pigs and 32 sheep

- 331/12: 35 cattle, 88 sheep and 259 pigs (returning to Waterford with slate and pipes)

The Liverpool was not quite up to the task, and after several slow runs it became clear that a faster ship would be desirable. In September 1887 she missed two buoys on her approach to Aberdovey, and ran aground, after which a light was fitted to her bows. She was replaced the following month by the 290 ton s.s Magnetic., which had been adapted for carrying livestock, but it soon emerged that this work was woefully inadequate. Green (1996, p.109-110) tells the story:

The Magnetic‘s second trip, on 26th October 1887, was a great disaster. She rolled abominably in severe gales, and the conversion had been done badly, with the stallage constructed at too low a level so that the beasts were thrown over the tops onto others in the next stalls. The ventilation was also quite inadequate. The had set sail with 149 head of cattle, and arrived with 21 of those dead, and a further 25 injured. A butcher from Towyn was sent for, and he slaughtered another three immediately, whilst the other 22 had to be sold off locally as being unfit for further travel. . . . There was a considerable legal wrangle over insurance, primarily because no cover had been ordered!

Having lost the trust of customers wishing to transport cattle, she became confined largely to small livestock, mainly pigs and some sheep. Local businesses were clearly aware that an expansion of the route to Ireland could replace the coastal trade, and were keen to build on the existing service, but not only were new services not established but in spite of its apparent success, the Waterford and Aberdovey’s operation was regrettably brief, closing at some point between 1888 and 1895 (harbour records are incomplete for the period).

The Aberdovey and Barmouth Steamship Company was founded in 1877. The company operated out of the offices of Liverpool wholesale grocers David Jones and Co., although they were not the only shareholders.

The best photograph I have found for the Dora so far is this one, showing her in Barmouth, c.1901. Source: People’s Collection Wales, which in turn scanned it from the U-Boat Project 1914-18 by Michael Williams.

Advert for the Dora. Source: Nefyn.com, which sourced it from Katie Hipwell and Claire Smith great grand-daughters of Captain Williams and their late father O G Williams (Gwyn) grandson of the Captain.

Their first ship was the iron-hulled screw steamer, the 162 ton s.s. Telephone, built in 1878 by H.M. McIntyre and Co of Paisley, replaced in 1900 by the 200-ton, three-masted s.s. Dora, known locally as The Grocery Boat. The two ships were registered in Liverpool. The steel-hulled Dora, also built in Paisley, by J. Fullerton and Co, was fitted with three masts and a single funnel set between the main (central) and mizzen (rear) masts. She was a weekly visitor to Aberdovey and the last ship to sail to and from Aberdyfi on a scheduled basis, carrying grain, cement, wood, timber, manure and sleepers. She departed from Liverpool every Friday stopping at Porthdinllaen, Barmouth and Aberdovey. The ship carried groceries, timber and animal food to Aberdovey, where they were met by local farmers who loaded horse drawn wagons from sheds on the wharf. She also carried passengers. You can find some more about the Dora at the Nefyn.com website.

Lewis Lloyd comments that “The steamers Telephone and Dora endeared themselves to the people of Aberdyfi and their regular ports-of-call. Their schedules represented normality and their passing meant a further reduction in the character of the coastal communities which they served.” There are several old photographs showing Dora, which usually, although by no means always, loaded and offloaded her cargo on the jetty’s inner berth. Dora was requisitioned for the Liverpool to Belfast route in November 1916.

Steamship Telephone. Source: Fenton 1989b, p.125

An interesting article in the Cambrian News and Merionethshire Standard dating to two years previous to the withdrawal of Dora from Aberdovey concerns the withdrawal of Telephone from Aberaeron, and may reflect some of the concerns that the loss of Dora may have caused. “Notes from Aberayron” opens with the statement “The most significant of all news for the week” was that s.s. Telephone would no longer connect Aberaeron with Liverpool with its “fairly large cargoes” on a fortnightly basis. The article says that it has been suspected for some time that the service was running at a loss, and this was now confirmed.

If the s.s. “Telephone” has gone for good, and if no new venture is in store which will put another boat on the trade, it will be a commercial loss to the community . . . . To lose the advantage of buying in the Liverpool markets means a good deal. The clients and customers of the Liverpool houses, too, will be cut off from Aberayron and that reduces the commercial status of the town.

If the s.s. “Telephone” has gone for good, and if no new venture is in store which will put another boat on the trade, it will be a commercial loss to the community . . . . To lose the advantage of buying in the Liverpool markets means a good deal. The clients and customers of the Liverpool houses, too, will be cut off from Aberayron and that reduces the commercial status of the town.

The article finishes with worries about the tyranny of monopoly and the dominance of the railway, but hopes that instead “the old, old relationship with Bristol” might remain unimpaired or even strengthened.

Dora was sunk by a German submarine, UC 65 under the command of Otto Steinbrink in 1917, when she was carrying aggregate on a trip to Ireland. The submarine surfaced and ordered the crew to disembark into the ship’s boats and return to shore, so there was no loss of life, but the ship was destroyed. In Aberdovey, the company did not resume service following the war, closing officially in 1918. Thanks to Eleanor Cole for the information that her grandfather Frank Morris, was one of Dora‘s crew, and after the war he worked on the Aberdovey golf course. His brother was a blacksmith in Tywyn and often worked on the Tal-y-Llyn railway.

In July 1895 the Cardigan Bay Steamship Company was formed in Pwllheli to offer a service between Pwllheli and Aberystwyth, calling in at Barmouth, Aberdovey and Aberystwyth. However, none of these destinations ever saw a ship, because potential investors were deterred by the existing services already offering a service to these ports, and after failing secure the necessary finance, the fledgling company closed.

Finally, the Liverpool and Cardigan Bay Steamship Company was founded in 1900 to run a service for the usual Cardigan ports from Liverpool. It purchased the Telephone, which had been replaced by the Dora, from the Aberdovey and Barmouth Steamship Company. As the main investors in the new company were the same Liverpool wholesale grocers David Jones and Co, who were the main investors in the Aberdovey and Barmouth Steamship Company the transaction must have been fairly painless. This was another short-lived service, closing in 1905.

Lewis Lloyd mentions other steamers that visited Aberdovey during and after the 1880s (1996, p.218-222). Included in his examination of the harbour records are those that visited in the last years before the war, including the steamers Ruby and Beryl, both carrying creosoted sleepers from Glasgow, the s.s. May and the s.s Countess of Warwick carrying summer day-trippers between Aberystwyth and Aberdovey, and the s.s. Gem from Ardrossan, carrying more sleepers 96528 if them).

Marconi’s steam yacht Elettra. Source: ARRL

In 1918, during Guglielmo Marconi’s tests of a radio station set up near Tywyn for transmission of wireless signals to America. Marconi (1874-1937) and and his team moored in Aberdovey in his absolutely stunning steam yacht Elettra. Elettra (meaning electron) is easily identifiable with her white hull, a long deeply raking clipper bow and stern, a single central funnel and two masts and neat rows of portholes. As a youngster, Kenneth Sturley, who later became a Marconi power engineer, spent his childhood holidays in Aberdovey, and tells the story of going aboard Elettra:

So I’d always watched with interest those aerials strung across from Tywyn. It was a long horizontal wire in those days, with low frequencies, of course, involved. Marconi occasionally came into Aberdovey Harbour with his yacht “Elettra,” in order to get to Tywyn from there, Tywyn being about five miles away. I heard that it was possible for one to make a request to go on the boat “Elettra”, and perhaps even see the great man. So I asked if I might do so, and was granted this opportunity. We went into the Morse-code cabin, and I duly put on the headphones and listened, and then the great man walked in. I’m afraid I was almost too tongue-tied to have much conversation with him. I remember very vividly, him coming in, but I can’t remember what he said. It certainly gave me a considerable kick, and made me realize that what I wanted to do was to be in radio.

Hugh M. Lewis comments in Pages of Time: “When the yacht berthed alongside the outer jetty, Marconi with his crew of young, good-looking Italians, were made very welcome in the village.” He includes a photograph showing her in Aberdovey, but it chops of both bow and stern and as she is simply shown on the sea with nothing showing Aberdovey itself, a different photograph here has been chosen to show the yacht’s main external features.

Enid Mary. Source: Fenton 1989b, p.112

After the war, few other regular commercial visitors arrived at the jetty, apart from fishing, boats. In the 1930s the Overton Steamship Company brought in shipments of cement for a while.

Finally, the Enid Mary, owned by British Isles Coasters came into Aberdovey around twice a year cargoes of superphosphate from the Netherlands, a fertilizer for local farmers.

Just as steam replaced sail, oil replaced steam. Two naval ships visited, and both were oil-fired: HMS Fleetwood in 1951 and the minesweeper HMS Dovey in 1987. The Aberdyfi lifeboat station has a rather special and unique feature: the bell from the HMS Dovey. It is on loan from the Royal Navy. Should another HMS Dovey be built, the bell will have to be returned, but at the moment it is a much loved and admired resident of the lifeboat station. The HMS Dovey was a river class minesweeper M2005 commissioned in 1984 and sold to Bangladesh in 1994 for use as a patrol ship. The last large visiting ship that I have been able to find reference to was the Royal Navy survey ship Woodlark, which spent 10 days surveying the approaches to the port in 1973.

Just as steam replaced sail, oil replaced steam. Two naval ships visited, and both were oil-fired: HMS Fleetwood in 1951 and the minesweeper HMS Dovey in 1987. The Aberdyfi lifeboat station has a rather special and unique feature: the bell from the HMS Dovey. It is on loan from the Royal Navy. Should another HMS Dovey be built, the bell will have to be returned, but at the moment it is a much loved and admired resident of the lifeboat station. The HMS Dovey was a river class minesweeper M2005 commissioned in 1984 and sold to Bangladesh in 1994 for use as a patrol ship. The last large visiting ship that I have been able to find reference to was the Royal Navy survey ship Woodlark, which spent 10 days surveying the approaches to the port in 1973.

One of the things that surprised me when I started writing this post and hunting for images was just how small most of these steamships were. I don’t know why I was expecting them to be substantially larger, because they were replacing small sailing coasters. Like their predecessors, they were true workhorses, and built to last. All of them retained masts from their sailing ancestry, usually two, as back-up for the engines and to save fuel when there was a good following wind.

The coming of the railway led to the decline and the eventual end of many small coastal ports. For a while sea and rail operated simultaneously, and at Aberdovey, ironically, all railway construction materials were landed by sea, leading to a brief spike in shipping activity. The decline of the slate trade, one of its primary coastal exports, was another contributing factor to Aberdovey’s deteriorating status as an active port. Businesses had clearly believed that running steamers in competition with the railways, by providing slower but cheaper cargo carriage, had genuine potential. The sheer number of steamship companies described above indicates that businesses refused to abandon the idea that steam could compete with rail, mainly trading regular perishable cargoes such as groceries, grain and, at the other end of the scale, non-perishable heavy goods like railway sleepers and ores that were not time-sensitive. The attempt to create a link with Ireland via the Waterford and Aberdovey Steamship Company must have given hope to Aberdovey, making use of the rail link with the port, but although it seemed to be quite well thought out, with animal pens provided for sending livestock on by rail, this eventually failed, perhaps because the demand for premium Irish livestock in expanding industrial areas was over-estitmated. Meanwhile, larger ports with good infrastructure benefited by becoming railway termini, where deep sea traders and the railways complemented one other.

Main sources:

Please note that not all accounts of the steamship companies listed above agree, particularly on foundation and liquidation dates. I have done my best to select what I think are the most probable of the various accounts by cross-referencing between the various sources of information, but if you are using this post as a preliminary step for research purposes, I urge you to read my sources below (particularly Green; Fenton; and Williams and Armstrong), and then explore their sources.

The National Library of Wales

https://newspapers.library.wales/

Fenton, R. 1976. Aberdyfi, its shipping and seamen (1565-1907). Maritime Wales/Cymru A’r Môr 1, p.22-46

Fenton, R. 1989a. Steam Packet to Wales: A chronological survey of operators and services. Maritime Wales/Cymru A’r Môr 12, p.54-65

Fenton, R. 1989b. Cambrian Coasters. Steam and motor coaster owners of North and West Wales. The World Ship Society.

Fenton, R. 2007. The Historiography of Welsh Shipping Fleets. Maritime Wales/Cymru A’r Môr 28, p.80-102

Green, C.C. 1996. The Coast Lines of the Cambrian Railways, volume 2. Wild Swan Publications

Lewis, H.M. n.d. Aberdyfi: Portrait of a Village

Lewis, H.M. n.d. A Chronicle Through the Centuries

Lewis, H.M. 1989 Pages of Time

Lloyd, L. 1996. A Real Little Seaport. The Port of Aberdyfi and its People 1565-1920. Volume 1.

Richards, J. 2007. Maritime Wales. Tempus

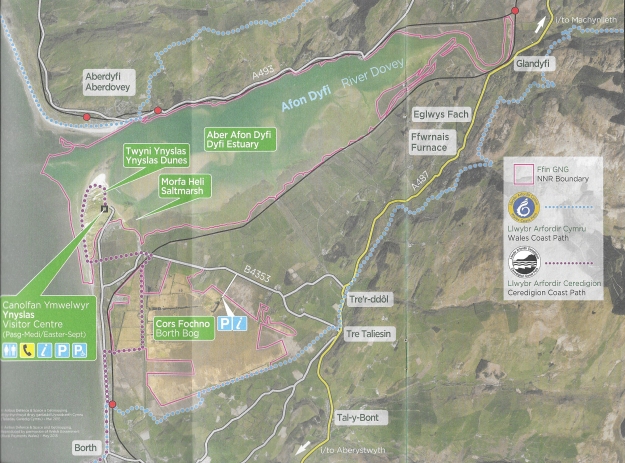

I was so sorry to hear that the excellent Ynyslas Visitor Centre has been threatened with closure by natural Resources Wales, without any public consultation. Fortunately, there is an active campaign to try to keep it open, but it is important that as many people as possible sign the petitions. The Visitor Centre is a terrific resource at the heart of the Ynyslas nature reserve, where I spent many happy hours walking through the sand dunes and collecting shells on the beach. This is a site of special scientific interest, and merits a visitor centre. The Visitor Centre itself is a lovely building where tea, coffee, sticky buns and relevant literature have always been available, together with information about the nature reserve itself.

I was so sorry to hear that the excellent Ynyslas Visitor Centre has been threatened with closure by natural Resources Wales, without any public consultation. Fortunately, there is an active campaign to try to keep it open, but it is important that as many people as possible sign the petitions. The Visitor Centre is a terrific resource at the heart of the Ynyslas nature reserve, where I spent many happy hours walking through the sand dunes and collecting shells on the beach. This is a site of special scientific interest, and merits a visitor centre. The Visitor Centre itself is a lovely building where tea, coffee, sticky buns and relevant literature have always been available, together with information about the nature reserve itself. NRW claimed they would continue with their statutory requirements to protect the site. However, members of the public pointed out that the staff at the centre are integral to protecting wildlife and the environment. They also play an important safety role and are essential to the nature education element of the site. Without proper management and vigilance, the delicate biodiversity at Ynyslas could be destroyed overnight. There is concern over an influx of unregulated campervans, large groups of motorbikes, poachers and people generally not understanding the importance of protecting the dunes.

NRW claimed they would continue with their statutory requirements to protect the site. However, members of the public pointed out that the staff at the centre are integral to protecting wildlife and the environment. They also play an important safety role and are essential to the nature education element of the site. Without proper management and vigilance, the delicate biodiversity at Ynyslas could be destroyed overnight. There is concern over an influx of unregulated campervans, large groups of motorbikes, poachers and people generally not understanding the importance of protecting the dunes.