Sun setting over the estuary this evening

3 Replies

I was so lucky this afternoon to see two wonderful oystercatchers on the foreshore. I was on the members’ terrace of the Literary Institute (I promise that I am a member and wasn’t trespassing!) and heard a high-pitched peeping noise coming from below. And there they were. Squinting into the sun, I suddenly saw two absolutely perfect little waders rushing around on their spindly pink legs picking up mussels from amongst the seaweed and bashing them with their long, strong orange beaks against the stones. You can hear the peeping and bashing noises on the video below. The camcorder did a remarkably good job, given that I was shooting straight into the sun. Oystercatchers also target cockles, limpets, small crabs and shrimps, all of which are available in the area. Although oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus) are common on coasts, and I have seen them at the mouth of the Dysynni, I have never seen one at Aberdovey before. I was utterly charmed. Wonderful to watch and to listen to them. When they took off, startled by some people walking along the foreshore, the lovely white streaks against the black of their wings were clearly visible.

I was so lucky this afternoon to see two wonderful oystercatchers on the foreshore. I was on the members’ terrace of the Literary Institute (I promise that I am a member and wasn’t trespassing!) and heard a high-pitched peeping noise coming from below. And there they were. Squinting into the sun, I suddenly saw two absolutely perfect little waders rushing around on their spindly pink legs picking up mussels from amongst the seaweed and bashing them with their long, strong orange beaks against the stones. You can hear the peeping and bashing noises on the video below. The camcorder did a remarkably good job, given that I was shooting straight into the sun. Oystercatchers also target cockles, limpets, small crabs and shrimps, all of which are available in the area. Although oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus) are common on coasts, and I have seen them at the mouth of the Dysynni, I have never seen one at Aberdovey before. I was utterly charmed. Wonderful to watch and to listen to them. When they took off, startled by some people walking along the foreshore, the lovely white streaks against the black of their wings were clearly visible.

Wednesday last week was one of those rare but gorgeous January days that provides a welcome reminder that spring lies ahead. Almost too good to be true. The tide was on its way out, always a beautiful sight as dips in the sand fill with still water reflecting the blue sky, and the millions of deeply scored fractal patterns in the sand are revealed, with the contrast of the dark shadows and bright surfaces always a sensational feature of the low winter sun. Apart from a few dog walkers the beach was almost empty, sensible people remaining in the warm.

My garden continues to be a source of wildlife activity, all the local species filling up on solid carbohydrates to see them through the bitterly cold nights.

The goldfinches, which turned up in my absence over Christmas, are now a daily presence, between two or seven of them at a time, four on the nyjer feeder with the others bouncing up and down in frustration in the tree. When they first arrived I was very taken by their beautifully minimalist movements and intricate eating habits, but when there are more than four trying to get onto the feeder at a time there can be real jockeying for position in a great thrashing of brightly coloured feathers, with some of the angelic looking little things chasing off others quite ruthlessly. A gaggle of goldfinches is called a “charm.”

Since I moved here in August, all the feeders have been popular, but in the last month the mixed seed feeder has been completely rejected, no matter where I hang it. Instead, most activity is concentrated on the fat ball, mealworm and peanut feeders. Do note that I put a soundtrack on the following video, just to get used to the software that I am using, but it is a really lovely piece of Bach, so hopefully not too intrusive.

Pictures of the Atlantic 85 in-shore lifeboat in action (photograph of part of a poster on display in the Aberdyfi Boat House).

The RNLI is a vital national emergency service dedicated to saving human life, comparable to the NHS Ambulance service, with the fundamental difference that its boats are manned largely by unpaid volunteers, its shops are manned wholly by unpaid volunteers and it is funded mainly by private donations, legacies and its own fund-raising efforts. The RNLI was established on 4th March 1824 as the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck, it was granted a Royal Charter in 1860, its Patron in Queen Elizabeth II and it has over 238 lifeboat stations and 445 lifeboats in England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and the Isle of Man. In Aberdovey alone the lifeboat goes out between 20 and 30 times a year, dragged to and from its home in the boat-house on the wharf by a giant, custom-designed caterpillar-tracked tractor.

The RNLI has a long and really fascinating history, and much of that will be explored in later posts, with special reference to the RNLI presence in Aberdovey since 1837, but here I want to start with what the RNLI does in Aberdovey today, how it works and what it means to sailors, people and animals in distress and the community as a whole.

The RNLI has a long and really fascinating history, and much of that will be explored in later posts, with special reference to the RNLI presence in Aberdovey since 1837, but here I want to start with what the RNLI does in Aberdovey today, how it works and what it means to sailors, people and animals in distress and the community as a whole.

Let’s begin with the guided tour of the facility that was given to me by Dai Williams, Volunteer Shop Manager at the RNLI. The lifeboat house in Aberdovey has moved around a lot since its establishment in 1837. However, in 1991 the Yacht Club and the RNLI combined resources to extend the clubhouse and accommodate a new lifeboat on the wharf. Most recently the wharf buildings were reconfigured in 2016 to allow the RNLI Lifeboat Station to expand, placing its new rescue boat the The Hugh Miles and its tractor under cover, improving the changing facilities for the lifeboat crew and moving the shop into a new location so that it is visible from the road and can benefit from passing footfall. Funding from private donors was central to the modifications to the premises, and the new RIB was enabled by a donation from The Miles Trust. The tractor is a massive and impressive beast on caterpillar tracks, a necessary adjunct to the boat due to the difficult recovery conditions at low tide.

The Hugh Miles, operating number B-896, is a fast inshore rescue craft, an Atlantic 85 rigid inflatable boat (RIB), replacing the previous Atlantic 75, Sandwell Lifeline. The RNLI has two main categories of lifeboat: all-weather lifeboats and inshore lifeboats, each of which are suited to different conditions. For the full range of lifeboat types employed by the RNLI see their “Our Lifeboat Fleet” web page. The Hugh Miles is a specialized inshore lifeboat, one of the fastest in the RNLI fleet, powered by two Yamaha 4-stroke outboard 115hp engines, reaching top speeds of 35 knots. It can go to sea in a force 7 wind during daylight hours and during a force 6 at night. It cost £214,000 and, at nearly a meter longer than its predecessor, has the capacity for an extra crew member, bringing the total to four, although it can operate with three, and far more kit. It is stored in a carriage, a cage on wheels, from which it is launched. The RIB has a solid bottom and flexible sides, which makes it both strong and relatively light-weight. The concept was originally developed in the Atlantic College, Vale of Glamorgan, south Wales during the 1960s and early 1970s. Watersports were a big part of the boarding school agenda, and the college had its own in-shore lifeboat station. They soon realized that the inflatable boat they were using could be improved upon and used marine plywood and rubber tube to create the templates on which the modern RIB is based. The RNLI recognized the idea and created a glass-reinforced fibre model, which was a B-Class Atlantic 21 that came into service in 1972, its name commemorating the role of the college for this and future B-type RIBs.

The Hugh Miles, operating number B-896, is a fast inshore rescue craft, an Atlantic 85 rigid inflatable boat (RIB), replacing the previous Atlantic 75, Sandwell Lifeline. The RNLI has two main categories of lifeboat: all-weather lifeboats and inshore lifeboats, each of which are suited to different conditions. For the full range of lifeboat types employed by the RNLI see their “Our Lifeboat Fleet” web page. The Hugh Miles is a specialized inshore lifeboat, one of the fastest in the RNLI fleet, powered by two Yamaha 4-stroke outboard 115hp engines, reaching top speeds of 35 knots. It can go to sea in a force 7 wind during daylight hours and during a force 6 at night. It cost £214,000 and, at nearly a meter longer than its predecessor, has the capacity for an extra crew member, bringing the total to four, although it can operate with three, and far more kit. It is stored in a carriage, a cage on wheels, from which it is launched. The RIB has a solid bottom and flexible sides, which makes it both strong and relatively light-weight. The concept was originally developed in the Atlantic College, Vale of Glamorgan, south Wales during the 1960s and early 1970s. Watersports were a big part of the boarding school agenda, and the college had its own in-shore lifeboat station. They soon realized that the inflatable boat they were using could be improved upon and used marine plywood and rubber tube to create the templates on which the modern RIB is based. The RNLI recognized the idea and created a glass-reinforced fibre model, which was a B-Class Atlantic 21 that came into service in 1972, its name commemorating the role of the college for this and future B-type RIBs.

Flicking through the Record of Service book in the life boat house there were a hair-raising number of minor and major incidences where the lifeboat was called out. These involved yachts and other sailing vessels, power boats including a fishing boat, canoes, inflatable dinghies, kite boards, sail boards, jet skis, an inflatable toy, and swimmers in trouble. Here are three examples of call-outs in 2018, all noted on the Aberdyfi Lifeboat’s Facebook page. In July, the lifeboat was called out to the assistance of swimmers in difficulty at Tywyn. On arrival, one casualty had been recovered but the second was still missing and the crew began a search, receiving information from the Coastguard that the swimmer had been spotted on the lifeboat’s exact course. The lifeboat proceeded as fast as was safe to the location where the helm manoeuvred the boat skilfully in the surf and shallow water to be able to put a crew member into the surf to recover the casualty with two members of the public who had waded in, recovered the second casualty. First aid was delivered and a second crew member from the lifeboat entered the surf with vital kit such as oxygen. It should be noted that whilst the second casualty survived, the first one died later in hospital, a tragic reminder of the importance of the work of the RNLI. One night in August at past 9pm, with the light fading and on an outgoing tide, the Aberdyfi Lifeboat was called out to a broken-down yacht. The lifeboat reached the yacht and the crew were able to secure a tow, bringing it back into the estuary and placing it on a mooring. The lifeboat was returned to its station by 11pm. At 1645 on an evening in September, the Aberdyfi Lifeboat was called out to aid a boat with eight people on board, which was experiencing engine problems and was aground just south of the Aberdyfi Bar. The Borth lifeboat was already on scene and had managed to tow the vessel into deeper water, and from there they handed the rescued boat over to The Hugh Miles, which took most of the boat’s crew on board and set up a tow to bring them back to the Dyfi estuary.

Flicking through the Record of Service book in the life boat house there were a hair-raising number of minor and major incidences where the lifeboat was called out. These involved yachts and other sailing vessels, power boats including a fishing boat, canoes, inflatable dinghies, kite boards, sail boards, jet skis, an inflatable toy, and swimmers in trouble. Here are three examples of call-outs in 2018, all noted on the Aberdyfi Lifeboat’s Facebook page. In July, the lifeboat was called out to the assistance of swimmers in difficulty at Tywyn. On arrival, one casualty had been recovered but the second was still missing and the crew began a search, receiving information from the Coastguard that the swimmer had been spotted on the lifeboat’s exact course. The lifeboat proceeded as fast as was safe to the location where the helm manoeuvred the boat skilfully in the surf and shallow water to be able to put a crew member into the surf to recover the casualty with two members of the public who had waded in, recovered the second casualty. First aid was delivered and a second crew member from the lifeboat entered the surf with vital kit such as oxygen. It should be noted that whilst the second casualty survived, the first one died later in hospital, a tragic reminder of the importance of the work of the RNLI. One night in August at past 9pm, with the light fading and on an outgoing tide, the Aberdyfi Lifeboat was called out to a broken-down yacht. The lifeboat reached the yacht and the crew were able to secure a tow, bringing it back into the estuary and placing it on a mooring. The lifeboat was returned to its station by 11pm. At 1645 on an evening in September, the Aberdyfi Lifeboat was called out to aid a boat with eight people on board, which was experiencing engine problems and was aground just south of the Aberdyfi Bar. The Borth lifeboat was already on scene and had managed to tow the vessel into deeper water, and from there they handed the rescued boat over to The Hugh Miles, which took most of the boat’s crew on board and set up a tow to bring them back to the Dyfi estuary.

David Williams, not to be confused with Dai Williams, is the Volunteer Lifeboat Operations Manager (LOM) at the RNLI in Aberdovey, leading the operation team. He is responsible for authorizing the launch of the lifeboat and ensure that the lifeboats and all associated gear are maintained and in a constant state of readiness for action. David Williams grew up in Tywyn and also volunteers with Mountain Rescue. In the event of his absence there are also four Deputy Launching Authorities who can stand in for him. The in-shore boat crew is headed by the Senior Helm (the equivalent of a coxswain on an the bigger all-weather boats), currently Will Stockford, who is also the Harbour Master and doubles up as boat mechanic. Next in seniority is the Helm, who must be on board if the Senior Helm is unavailable. The helm is trained in a variety of skills including navigation, search and rescue and casualty care, has many years experience as a volunteer and is in charge of leading any rescue. Three other crew members may or may not be trained to steer and navigate the boat but all receive their initial training in Poole in Dorset at the RNLI. As well as being on call for emergencies, the crew undergo practice drills and training on a weekly basis, usually on a Sunday morning. The tractor drivers are usually former crew members who have retired.

David Williams, not to be confused with Dai Williams, is the Volunteer Lifeboat Operations Manager (LOM) at the RNLI in Aberdovey, leading the operation team. He is responsible for authorizing the launch of the lifeboat and ensure that the lifeboats and all associated gear are maintained and in a constant state of readiness for action. David Williams grew up in Tywyn and also volunteers with Mountain Rescue. In the event of his absence there are also four Deputy Launching Authorities who can stand in for him. The in-shore boat crew is headed by the Senior Helm (the equivalent of a coxswain on an the bigger all-weather boats), currently Will Stockford, who is also the Harbour Master and doubles up as boat mechanic. Next in seniority is the Helm, who must be on board if the Senior Helm is unavailable. The helm is trained in a variety of skills including navigation, search and rescue and casualty care, has many years experience as a volunteer and is in charge of leading any rescue. Three other crew members may or may not be trained to steer and navigate the boat but all receive their initial training in Poole in Dorset at the RNLI. As well as being on call for emergencies, the crew undergo practice drills and training on a weekly basis, usually on a Sunday morning. The tractor drivers are usually former crew members who have retired.

Dai Williams is the Volunteer Shop Manager, currently with a team of six shop volunteers helping customers in the shop. The RNLI shop on the wharf not only generates important funds for the charity but raises awareness of the RNLI and its activities, its staff acting as ambassadors for the lifeboat station, explaining its role and answering the many questions from the public. The new merchandise in the shop is bright, modern and eclectic, offering everything from games and toys to calendars and diaries, as well as souvenir tea towels, mugs and clothing is provided by the RNLI. Nautical themes dominate, of course, and many are by designer names. There are also shelves outside selling second hand books, jigsaws and DVDs donated by the public. Having spent some time in the shop over the last month, it has been great to see the range of people who visit and buy products in support of the RNLI. Small children with their parents, buying nets, shovels and buckets for crabbing are very happy contributors to RNLI funding. I have been buying RNLI Christmas cards online for years, but it’s much better to be able to go and buy them in person. And just about everyone is getting an RNLI tea towel in their stockings this year!

Dai Williams is the Volunteer Shop Manager, currently with a team of six shop volunteers helping customers in the shop. The RNLI shop on the wharf not only generates important funds for the charity but raises awareness of the RNLI and its activities, its staff acting as ambassadors for the lifeboat station, explaining its role and answering the many questions from the public. The new merchandise in the shop is bright, modern and eclectic, offering everything from games and toys to calendars and diaries, as well as souvenir tea towels, mugs and clothing is provided by the RNLI. Nautical themes dominate, of course, and many are by designer names. There are also shelves outside selling second hand books, jigsaws and DVDs donated by the public. Having spent some time in the shop over the last month, it has been great to see the range of people who visit and buy products in support of the RNLI. Small children with their parents, buying nets, shovels and buckets for crabbing are very happy contributors to RNLI funding. I have been buying RNLI Christmas cards online for years, but it’s much better to be able to go and buy them in person. And just about everyone is getting an RNLI tea towel in their stockings this year!

As well as the shop there is also an important fund-raising group based locally, the Aberdyfi Lifeboat Guild, which puts on events throughout the year. Many terrific visitor activities take place, particularly during the course of the summer, which get everyone involved, from crew to visitors, from young to old. Events have included Flag Day when there was a duck race (500 plastic ducks are launched and then retrieved!), the Abergynolwyn Silver Band played, there was a raft race and an afternoon tea was organized. Other events have included a quiz night, a Crabby Competition, a barbecue, the Dysynni Male Voice Choir and a Fun Run. There was even a stand at the Food Festival in August, demonstrating water health and safety procedures and equipment, and the Lifeboat Station has a stall at the Christmas Fair (this year on the 1st December, 10am – 4pm).

Donations from the public continue to be critical to the operations of the RNLI. The donations that enabled the modernization of the Aberdovey RNLI base says a lot about the sort of people who help the RNLI not merely to continue operating, but to continue updating their technology and improving their services. The Miles Trust, which funded the new boat, was set up in memory of Hugh Miles. Hugh Miles, the only child of the late Herbert and took great pleasure in RNLI activities around South Wales and after his death his mother bequeathed her estate to the RNLI, part of which was to be used to fund a rescue boat for the Welsh coast. The Aberdovey’s The Hugh Miles Atlantic 85 RIB is that boat. The modification for the boathouse was funded by the Derek and Jean Dodd Trust and a legacy left to the charity by RNLI supporter Desmond Nall. Derek and Jean Dodd moved near Aberdovey, where Derek was able to kayak into his 80s. Desmond Nall was an RNLI enthusiast from Solihull, who, together with his brother, Godfrey volunteered on the RNLI’s stand at the Birmingham Boat Show for a number of years and funded two inshore lifeboats.

The Aberdyfi lifeboat station has a rather special and unique feature: the bell from the HMS Dovey. It is on loan from the Royal Navy. Should another HMS Dovey be built, the bell will have to be returned, but at the moment it is a much loved and admired resident of the lifeboat station. The HMS Dovey was the river class minesweeper M2005 commissioned in 1984 and sold to Bangladesh in 1994 for use as a patrol ship.

The Aberdyfi lifeboat station has a rather special and unique feature: the bell from the HMS Dovey. It is on loan from the Royal Navy. Should another HMS Dovey be built, the bell will have to be returned, but at the moment it is a much loved and admired resident of the lifeboat station. The HMS Dovey was the river class minesweeper M2005 commissioned in 1984 and sold to Bangladesh in 1994 for use as a patrol ship.

If you are a visitor to Aberdovey, do visit the lifeboat station and the shop. You will find a very warm welcome.

Contact details:

Aberdovey Lifeboat Station

The Wharf

Aberdyfi

LL35 0EB

01654 767695 (If you see someone in trouble at sea dial 999 and ask for the Coast Guard).

The shop is open from Easter to October 10am–4pm Saturday and Sunday, and on some Saturdays in November and December. During the summer it is open for some days during the week (opening times are shown in the shop door)

Facebook page

As well as the RNLI, local emergency services that receive no direct government funding and rely on their charity status and fundraising activities for their income are Trinity House (vital shipping and seafaring charity), the Wales Air Ambulance service and Aberdyfi Search and Rescue.

Many thanks to Dai Williams for correcting the mistakes and plugging the gaps in my first draft. Helen Williams tells me that no matter how much you find out about the lifeboat station, there is always more to know and I believe her!

Aberdyfi Lifeboat Facebook page

https://bit.ly/2OXFbqx

Dermody, D. 2011. Atlantic College students’ RIB sea safety revolution. BBC 15/05/17. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-south-east-wales-13377377

RNLI News Release 2016. Farewell to Sandwell Lifeline as Aberdyfi RNLI welcomes new lifeboat. RNLI 02/12/16. https://rnli.org/news-and-media/2016/december/02/farewell-to-sandwell-lifeline-as-aberdyfi-rnli-welcomes-new-lifeboat

RNLI News Release 2017. Double celebration ahead for Aberdyfi RNLI. RNLI 25/07/17.

https://rnli.org/news-and-media/2017/september/25/double-celebration-ahead-for-aberdyfi-rnli

RNLI News Release 2018. Aberdyfi and Barmouth RNLI Lifeboats involved in Tywyn rescue. RNLI 1/08/18. https://rnli.org/news-and-media/2018/august/01/aberdyfi-and-barmouth-rnli-lifeboats-involved-in-tywyn-rescue

Overlooking Aberdovey’s sea front is a little white shelter on a small hillock, a popular destination with tourists and dog walkers known in the 19th Century as Pen-y-Bryn, which translates as Head of the Hill. The original name of the hill may have been Bryn Celwydd, Hill of Lies, which is recorded on a chart of the Dyfi Estuary dating to 1748. A number of guides to Aberdovey place Aberdyfi Castle on that spot. For example, in Aberdyfi: The past Recalled by Hugh M. Lewis has a page describing the castle, “possibly a motte and bailey castle or more probably a castle of wattle and daub which was defended by a stockade,” locating it at Pen-y-Bryn. However, although it is recorded that certain historical events clearly took place at a castle of this name, and it receives particular mention in the late 12th-early 13th Century Brut-y-Tywysogion (Chronicle of the Princes) compiled at Strata Florida abbey, the identification of the castle with the bandstand hill, and even with Aberdovey itself, is very doubtful.

To begin with, Pen-y-Bryn always seemed to me a most improbable as the site of a castle, even a small one, even allowing for substantial alteration of the profile of the hill over time. In a motte and bailey arrangement a fortification sits on a natural or artificial mound with an accompanying settlement in a walled/fenced area at its foot, sometimes surrounded by a moat or ditch. Pictures of ruins and artistic reconstructions based on excavations indicate that the motte might support a fortification that was little more than an elaborate shed, as this reconstruction from the Dorling Kindersley Find Out website suggests. That nothing substantial could have been built on the Pen-y-Bryn site does not rule it out of being Aberdyfi castle, but the events that are described below would indicate that a large structure would have been required to defend an important fortified settlement, particularly one selected for the vital political assembly that established the primacy of a Welsh prince as ruler of most of Wales.

Dorling Kindersley reconstruction of a motte and bailey castle showing the main features. Fortifications could be very small. Source: Dorling Kindersley Find Out website.

The Aberdyfi Castle was twice used as a base for important documented meetings of Welsh rulers, first in the 12th and then in the 13th Century, but the name is also connected with a much less secure event that allegedly took place in the 6th Century. A rather more plausible alternative to Pen-y-Bryn for the castle is the site of Dolmen Las on the south bank of the Dyfi at Glyndyfi in Ceredigion, suggested by a number of authors.

What is clear is that wherever the castle was located, it was a Welsh one, rather than an English one captured by the Welsh. The Norman invaders were innovators of the use of castles in Wales, but it was not long before Welsh leaders, observing and suffering the effects of this new powerful strategic device, were able to learn from it and build their own versions. Rhys ap Gruffudd the powerful 12th century ruler of Deheubarth was amongst the first to take to castle building, and in his biography of Rhys, Turvey suggests that this castle was one of his.

What is clear is that wherever the castle was located, it was a Welsh one, rather than an English one captured by the Welsh. The Norman invaders were innovators of the use of castles in Wales, but it was not long before Welsh leaders, observing and suffering the effects of this new powerful strategic device, were able to learn from it and build their own versions. Rhys ap Gruffudd the powerful 12th century ruler of Deheubarth was amongst the first to take to castle building, and in his biography of Rhys, Turvey suggests that this castle was one of his.

Aberdyfi is first connected with Maelgwyn Fawr (Maelgwyn the Great, Maglocunus in Latin), descendant of Cunedda, and ruler of Gwynedd. This is mentioned by Davies who says that “according to tradition it was at Aberdyfi that the suzerainty of Maelgwyn Fawr had been recognized seven hundred years earlier.” This apparently endowed Aberdfyi with a certain status as a place associated with the triumph of a Welsh ruler in achieving a status approaching that of a king.

Effigy of Rhys ap Gruffudd from St David’s Cathedral. Source: Wikipedia

According to Turvey, Aberdyfi Castle itself seems to have been founded by Rhys ap Gruffydd (1132-1197) in 1156, the ruler of Deheubarth, the second most important region in Wales, in order to counter the expansionist policies of Owain Gwynedd (or Owain ap Gruffudd, 1100-1170), ruler of the most important region at the time, Gwynedd. Rhys and his brothers had invaded Ceredigion in 1153, having already consolidated their position in Dyfed and Ystrad Tywi, and by the time Henry II came to power, John Davies says that Owain Gwynedd’s realm “extended almost to the walls of Chester,” taking in much of the earldom of Chester and the kingdom of Powys. The northern frontier of Deheubarth and the southern border of Gwynedd met at the river Dovey, making the river strategically significant. Rhys was continually at war with the Norman Marcher lords to the east, and in 1158 Roger de Clare captured the castle in but was ousted by Rhys in the same year.

Llywelyn the Great with his two sons, by the Benedictine monk Matthew of Paris (1200-1259). Source: Wikipedia

In 1216 an important meeting took place at Aberdyfi Castle, 15 years after the death of Rhys. Its purpose was to formalize the position of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (c.1173-1240), grandson of Owain Gwynedd who became known as Lywelyn Fawr (Llwelyn the Great), to receive the homage of other Welsh rulers and to divide Deheubarth among the descendants of Rhys ap Gruffudd. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth was born in Gwynedd, which throughout the early Middle Ages had shown the most promise for becoming the leading territory in Wales and a unifying force for the various regions that made up Wales. The assembly was intended to reinforce the position of Llywelyn as pre-eminent ruler in Wales. At the Aberdyfi castle gathering minor rulers of the Deheubarth territory confirmed their homage to Llywelyn, and in return Llywelyn divided Deheubarth amongst the descendants of its deceased ruler Rhys ap Gruffudd. Aberdyfi Castle was probably chosen for the meeting partly because of the Maelgwyn Fawr connection, lending historical gravitas and integrity to the event.

So where was Aberdyfi Castle? Even though it has been claimed that there may have been a Welsh fortification on the bandstand site, it is clearly not a suitable venue for the types of assembly described above. Instead, a far more probable venue is Domen Las, which appears to be the remains of a motte at Ysgubor y Coed near Glandyfi (translating as bank of the river Dyfi) on the south side of the river Dyfi in Ceredigion, map reference SN68729687. This fits in with the identification of Rhys as its builder and its location in his Ceredigion territory in Deheubarth. The name Aberdyfi simply means “mouth of the Dyfi” and although Glandyfi is not at the mouth of the estuary, it is located at the point at which the river begins to open out into the estuary and may have been a crossing place. More significantly, Domen Las faced the mound of Tomen Las near Pennal in Gwynedd (SH697002), which may have been a motte established by one of the Gwynedd rulers, and possibly in use at the time that Aberdyfi Castle was built. In addition, from Owain Gwynedd’s point of view, there would have been an obvious strategic link between Gwynedd and Deheubarth. Dividing up Deheubarth from a point within Deheubarth but just over the border from Gwynedd and in sight of it would have been a powerful message to the descendants of Rhys. Finally, although the 6th Century Maelgwn association with Aberdyfi pre-dates Rhys’s castle by five centuries, it may have had something to do with the castle’s name.

Domen, meaning mound, and las meaning green in old Welsh (blue in modern Welsh) describes the site perfectly. It is an overgrown mound on the edge of the river Dyfi. John Wiles describes it as follows on the excellent Coflein (The online catalogue of archaeology, buildings, industrial and maritime heritage in Wales) website:

The medieval castle of Domen Las is represented by a castle mound or motte. This is notable for the way that it is fitted into the natural topography and for the remarkable configuration of its ditch.

The castle faces north-east across the upper Dyfi estuary towards Pennal, the court of the Princes of Gwynedd in Merioneth (see NPRN 302965), and was built in 1156 to counter those Princes’ ambitions in Ceredigion. It may then have been the sole castle in Geneu’r-glyn commote, as Castell Gwallter at Llandre is not heard of after 1153 (see NPRN 92234). Domen Las is probably the castle of Abereinion mentioned in 1169 and 1206.

Domen Las in the bird sanctuary Ynys Hir. The small wooden building is a bird hide. Source: Castles of Wales website. Photograph by John Northall, copyright John Northall

The castle mound is set near the northern tip of an isolated straggling rocky ridge rising from the marshes. It is a circular flat-topped mound roughly 34m in diameter and 5.0m high. It is ditched around except on the south-east, where the ground falls steeply into the marsh. On the west side a rocky ridge serves is co-opted as a counterscarp. On the north side the ditch has the appearance of a regular basin, closed on the east side by a wall of rock pierced by a narrow gap. This could be a pond or cistern, and is surely an original feature.

There are no traces of any further earthworks. The castle mound was probably crowned by a great timber-framed tower and it is likely that a princely hall and associated offices stood nearby. These could have occupied the irregular platform on the northern tip of the spur above the river, although there is a more a more amenable location on the south side of the motte, where a level area is sheltered by the rocky ridge. A little to the south a small bank cuts across the ridge. This was probably a hedge bank and may be comparatively recent.

The identification of Domen Las as Abereinion castle by Wiles and others is interesting and muddies the waters more than somewhat. The River Einion flows into the Dovey very near Domen Las but there is also a River Einion to the south, and in The Welsh Chronicle it is listed as having been built by Malgwn in 1205 and is sometimes identified with the mound at Cil y Graig in Cardigan as Abereinion Castle. It is entirely possible, of course, that both names were applied to the same castle. If that were the case, the Domen Las site is the most plausible location as it is both at the mouth of the river Dovey, where it spreads into the estuary, and at the mouth of the river Einion, where it joins the Dovey.

Location of Tomen Las (click to expand the image). Sources: Main map from Google Maps; Insert from the Coflein website.

Another candidate for Abyerdyfi Castle is Tomen Las near Pennal. This is actually within Gwynedd with clear views over the estuary to Ceredigion and to Domen Las. At the south of Gwynedd, near the borders with Deheubarth, this is yet another plausible site. The Coflein website suggests that it was a former court (llys) of the princes of Pennal and describes the surviving remains as a circular mound 26m in diameter that rises 3.0m from the traces of its ditch with a level summit 15-17m across. There are no traces of further earthworks.

The short answer to the question posed in the title of this post is that there is no definitive location for Aberdyfi Castle. I have searched for but failed to find any records that the Pen-y-Bryn or Domen Las sites have been excavated, but it would certainly be interesting if future research into the question were to extend beyond analysis of the late Medieaval texts and into the field. If I had to put money on it, I would go for the Domen Las site, mainly because of the political significance of the location just over the border of Gwynedd in Ceredigion, a good location from which to make a statement about the dominance of Llewelyn ab Iowerth over both Gwynedd and the Deheubarth territories to its south.

Finally, returning to Pen-y-Bryn, a booklet by the Aberdyfi Chamber of Trade says that the castle on the hill was built by Rhys ap Gruffydd in 1151, when it was called Bryn Celwydd and was destroyed in 1157 by the Norman Earl Robert de Clare. The little shelter at its top was a gift from a local landowner in 1897. It can be approached from a footpath on the left as you head up Copper Hill Street, or from the seafront road just on the town side of the railway bridge, along a track that has recently been restored after several years of closure. It looks as though you are heading into someone’s garden, but the steps that lead up on the far right are part of the footpath. From the shelter there are beautiful views over the Dovey estuary and Cardigan Bay.

Finally, returning to Pen-y-Bryn, a booklet by the Aberdyfi Chamber of Trade says that the castle on the hill was built by Rhys ap Gruffydd in 1151, when it was called Bryn Celwydd and was destroyed in 1157 by the Norman Earl Robert de Clare. The little shelter at its top was a gift from a local landowner in 1897. It can be approached from a footpath on the left as you head up Copper Hill Street, or from the seafront road just on the town side of the railway bridge, along a track that has recently been restored after several years of closure. It looks as though you are heading into someone’s garden, but the steps that lead up on the far right are part of the footpath. From the shelter there are beautiful views over the Dovey estuary and Cardigan Bay.

References

Aberdyfi Chamber of Commerce 2003. Aberdyfi Aberdovey Walks.

Davies, J. 2007 (revised edition of the 1990 and 1992 editions). A History of Wales. Penguin

Jenkins, G.H. 2007. A Concise History of Wales. Cambridge University Press

Lewis, H. M. 2001. Aberdyfi: The past Recalled. Dinas

Turvey, R. 1997. The Lord Rhys: Prince of Deheubarth. Gomer.

Wiles, J. 2008. Domen Las or perhaps Abereinion Castle. Coflein. http://www.coflein.gov.uk/en/site/303600/details/domen-las-or-perhaps-abereinion-castle

We drove to from Aberdovey to the Ynyslas Nature Reserve, via our visit to the Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace, just to check out the location of parking and the visitor centre, prior to a proper visitor at a later date. Ynyslas is immediately opposite Aberdovey across the estuary. It is a landscape of sand dunes and soft colours. The views over Aberdovey were super, providing a really good impression of the layout and extend of the place. It looks so much bigger from across the estuary! Here are three of the views taken from Ynyslas today. I’ll be going back to explore the walks on the next suitable day.

Today my father and I visited the site of the Royal Silver Mint and the restored Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace at the village of Furnace (Welsh Ffwrnais), only 10km southwest of Machynlleth on the south side of the Dovey river, in Ceredigion. What an amazing place. Some of my days out have nothing much to do with Aberdovey itself, but this one is positively bristling with linkages between the 18th Century Dyfi Furnace and the contemporary port at Aberdovey.

Today my father and I visited the site of the Royal Silver Mint and the restored Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace at the village of Furnace (Welsh Ffwrnais), only 10km southwest of Machynlleth on the south side of the Dovey river, in Ceredigion. What an amazing place. Some of my days out have nothing much to do with Aberdovey itself, but this one is positively bristling with linkages between the 18th Century Dyfi Furnace and the contemporary port at Aberdovey.

Learning of the existence of the Dyfi Furnace was a complete accident. Last week my father and I drove into Aberystwyth to find out how long it would take to drive there from Aberdovey, and if there were retail facilities worth the trip. The drive was surprisingly beautiful, mainly through lovely woodland and pastures, sometimes with views over the river Dovey, the estuary and Cardigan Bay, with a spectacular descent into Aberystwyth itself, the sea a staggeringly beautiful blue. The reality of the eternally winding road meant that we were plagued with nervous and over-cautious drivers and very slow lorries, a frustrating experience behind the steering wheel. On the other hand, discovering the Dyfi Furnace was an absolutely excellent outcome of the expedition.

As we hurtled around a corner on our way to Aberystwyth, we both noticed a large water wheel on the side of an impressively solid stone-built building on the left/east of the A487, a few miles southwest of Machynlleth. When we returned from Aberystwyth I fired up my PC to find out what it was, and having identified it as Dyfi Furnace, started investigating its past. The two buildings that make up the site are managed by Cadw, and the site has a long and absolutely fascinating history dating to at least the 17th Century, spanning the reign of Charles I, the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution and the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Today it has a valuable role welcoming visitors and providing information about the area’s industrial past.

As we hurtled around a corner on our way to Aberystwyth, we both noticed a large water wheel on the side of an impressively solid stone-built building on the left/east of the A487, a few miles southwest of Machynlleth. When we returned from Aberystwyth I fired up my PC to find out what it was, and having identified it as Dyfi Furnace, started investigating its past. The two buildings that make up the site are managed by Cadw, and the site has a long and absolutely fascinating history dating to at least the 17th Century, spanning the reign of Charles I, the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution and the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Today it has a valuable role welcoming visitors and providing information about the area’s industrial past.

There is a lot to say, so this is a long post, divided up as follows:

All sources used throughout the post are listed at the end. You can click on images to see larger versions.

The site is located c.10kms south of Machynlleth on what is now the A487. On the Ordnance Survey map, at SN685951 it can be found on the edge of the village of Furnace, which took its name from the Dyfi Furnace. The Dyfi Furnace is one of the last charcoal blast furnaces is to be preserved in Britain and is the best preserved in Wales. It is now managed by Cadw, Welsh Government’s historic environment service.

The site is located c.10kms south of Machynlleth on what is now the A487. On the Ordnance Survey map, at SN685951 it can be found on the edge of the village of Furnace, which took its name from the Dyfi Furnace. The Dyfi Furnace is one of the last charcoal blast furnaces is to be preserved in Britain and is the best preserved in Wales. It is now managed by Cadw, Welsh Government’s historic environment service.

The history of the Dyfi Furnace can be divided into five phases of use:

All three phases of use depended on water power, employing water wheels of varying sizes to transmit energy to operate machinery.

The early 17th Century lead works

In the early 17th Century, Sir Hugh Myddleton was responsible for promoting the metal mining industry in Ceredigion, with remarkable success, although he is better known for his pivotal role in the construction of the New River, to supply water from the River Lea to London. It is thought that the Ynsyhir lead smelting works, that were the first industrial works standing on the Dyfi Furnace site were part of his drive to bring industry to the area. The lead works dated from around 1620, processing lead ore to produce both lead and silver. As in later years, local wood was probably the main reason for siting the lead works in this particular place. The finished products were distributed by sea via the Dyfi estuary, helping to establish Aberdovey as an important trans-shipping port.

During the reign of Charles I (1600-1649) silver coinage was produced in the Royal Mint in London from silver produced in mines throughout Britain, including Wales. The crown owned a number of silver mills in its own right, known as the Mines Royal. A paper by the Reverend Eyre Evans describes a surviving petition from 1636 that states that on the 12th May 1625 Charles I had granted one Sir Hugh Myddleton with the rights, for 31 years, to all the silver mines in the county of Cardigan, to be sent to the Royal Mint in London. By the end of 1636 silver had been sent to the Mint at a value of £50,000. The petition was sent by Thomas Bushell, member of the Society of Mines Royal, who had bought the land on Myddleton’s death from from Myddleton’s widow and hoped to retain Royal patronage for the endevour.

Bushell was granted his petition, and now in the possession of the mines began to petition for a mint (a coin factory) in Aberystwyth Castle to manufacture coins exclusively from Welsh silver mines, citing the precedent of Ireland, where a Royal Mint had been established. Rather surprisingly, given strongly worded objections from the Royal Mint in London, on the 9th July 1637 Bushell was again granted his wish, and was authorized to coin the half-crown, shilling, half-shilling, two-pence, and penny, all from Welsh silver. In October of the same year the groat, threepence and half-penny were added to the list. A set of accounts for the Aberystwyth Castle mint last up until 1642, when they cease abruptly, almost certainly due to the outbreak of the Civil War and the threat to the mint from Parliamentarian forces, and the castle was actually occupied briefly in 1648.

Tentative suggestions that during the Civil War (1642-1651) the Aberystwyth Royal Mint was moved to the site at Furnace were unambiguously confirmed during the 1986 excavations by James Dinn and his team, a great result. Ceredigion silver was very highly valued and moving the Royal Mint to this location was a sound plan, particularly as Charles I was in urgent need of coin to pay his army. This seems to have taken place in 1648 or a short time beforehand.

The silver mill had been described by Sir John Pettus and John Ray in 1670 and 1674 respectively, and a plan by Waller (1704) survives. These between them describe furnaces, possibly up to five of them, the mint house and the stamping mill surrounding a courtyard, together with the mint house, a lead mill and a refining house. Between them the buildings had four water wheels to operate four sets of bellows. One of the wheel pits was found during the excavations. A cobbled surface was also found during excavations, apparently belonging to the courtyard of the silver mill.

Dinn says that the dates during which the silver mill was in use are uncertain, but that it may have operated in 1645-6 and 1648-9. Activity was apparently suspended in 1650 but the works seem to have been in operation again in 1650. 1670 seems to mark the date for its permanent abandonment.

Introducing the Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace

The Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace was built in c.1755 and was in use for five years for iron smelting (the production of iron from natural iron ore). The excavations found that later conversion to a sawmill had destroyed some of the blast furnace components but preserved others. Charcoal blast furnaces had been introduced into Britain in the late 15th Century but it took another century for them to become widespread.

The furnace was initially leased in c.1755 from Lewis and Humphrey Edwards by Ralph Vernon together with the brothers Edward and William Bridge, who had been involved with the building of a furnace in Conwy, north Wales in 1750. The furnace-master, who was accommodated in a house at the site called Ty Furnace, was Thomas Gaskell. Vernon retired sometime between 1765 and 1770 and the Bridge brothers went bankrupt in 1773. Dinn says that this “left members of the Kendall family in sole control of Conwyy and Dyfi furnaces.” I am not clear on how the Kendalls, west Midlands iron-masters with interests throughout Britain, came to be in control, but the Kendalls may have invested in the furnace operation. Ralph Vernon was a cousin of Jonathan and Henry Kendall and they had been in business together before. Both Dyfi and Conwy furnaces were put up for sale in 1774. No buyers were found and it is thought that John Kendall probably managed the Dyfi furnace himself until his death in 1791, but the Conwy furnace closed in around 1779. In 1796 the lease again changed hands and was now in the name of Messrs Bell and Gaskell, the latter being the Thomas Gaskell who had been the furnace master at Dyfi Furnace under the Kendalls. Dyfi Furnace went out of use as an iron ore smelting furnace in around 1810.

There were four reasons for basing the furnace at the foot of the River Einion waterfall.

There were four reasons for basing the furnace at the foot of the River Einion waterfall.

Both iron ore and limestone had to be imported. The iron ore came mainly from Cumbria, but it is not clear where the limestone was sourced. Limestone is available in north Wales, and there are records of imports to the furnace from the River Dee, so this is a plausible source.

The entire complex included the Furnace (blast furnace stack, the hearth at its base, a casting house, a bellows room, a counterweight room, a charging room), an external charcoal storage building and the iron-master’s house, Ty Furnace.

The job of the charcoal blast furnace, and how it works

Iron Smelting

A furnace is an impressive combination of chemical and mechanical engineering.

Iron ores are a mixture of oxides and sulphates of iron, predominantly haematite, ferric oxide (Fe2O3). However, the haematite and other iron oxides come mixed with a variety of other minerals, containing such elements as silica, alumina, phosphorous, manganese and sulphur. The smelting process must accomplish two things.

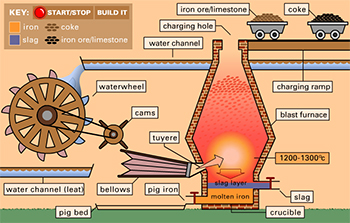

Blast Furnace simulation showing some of the components described in this post. Please note that this simulation shows coke being used, but this is a later innovation; the Dyfi Furnace used charcoal. Sourced from the BBC History website, where it can be run as an excellent Flash animation.

It must split the molecules of the iron compounds so that the iron is separated from the oxygen. This is done by the addition of heat and the supply of carbon in the form of (in this case) charcoal. In this chemical and physical environment, the addition of heat energy divides the ore into iron and carbon dioxide, CO2. The hot carbon dioxide exits through the chimney. Notice that the charcoal is both the source of heat, and a chemical reagent combining with the oxygen in the ferric oxide.

The second thing the process must accomplish is remove the other minerals that accompany the haematite in the iron ore. This is achieved in two ways. First, the addition of intense heat acts in much the same way as it does with the haematite taking off some of the impurities as gases. However, it also requires the addition of a limestone (primarily composed of calcite, CACO3) “flux,” which both lowers the melting point of the mixture and bonds with the impurities to make a silicaceous liquid, physically and chemically similar to a very impure glass. Being silicaceous, it is light and floats on the iron, making it relatively easy to separate.

The addition of oxygen

Oxygen is added by use of bellows. There are two features of the flow of air in a furnace which are worth noting. First the bellows are much more effective blowing into a confined space. Blowing into an open hearth, the air is quickly dissipated, as is the heat produced. Second, the narrow funnel at the top of the furnace creates what engineers call a “venturi.” It forces the hot rising gases into a much smaller space so that their speed increases, in the same way that like the narrowing of the nozzle size on a hose pipe, increases the speed at which the water squirts out. When the velocity of a gas increases, its pressure falls, according to a physical law known as Bernoulli’s principle. The low pressure at the top of the furnace pulls the air through the smelting mixture just as the air from the bellows is pushing it. Together, they increase the amount of oxygen from the air which reaches the burning charcoal, radically increasing its temperature.

Bellows

Bellows are a device for taking a lot of air from an unconfined place and pushing it at high pressure into a smaller place. To operate successfully the bellows need four features.

First, and most obvious, a bag into which the air can be sucked from the atmosphere. At this time the bag were usually leather.

The second thing that the bellows need are a way of opening and closing the bag. In this furnace opening is achieved by a cog with one side of each tooth rounded (see diagram), driven by a water wheel. The opening is achieved by a counter weight connected to a lever which is pulled up by the same cog mechanism (see diagram). When the tooth of the cog passes, the counterweight falls to open the bellows.

The third thing is a valve on the leather bag which lets air be sucked in when the bellow are open, but not blown out when they are closing.

Finally, the bellows need a narrow nozzle to push the air at high speed into the furnace chamber to deliver oxygen to the charcoal and increase the rate of combustion.

A Cadw sign from the site showing how the counterweights related to the functionality of the bellows

How the iron smelting process translates into furnace architecture

The furnace consists of a number of different rooms, each devoted to a different task:

Looking in detail at the Dyfi Furnace

When it was built in c.1755 the Dyfi Furnace appears to have consisted of a free-standing blast furnace, with other components added a little later. The completed complex consisted of the furnace building made of local shale from the Silurian period Llandovery series and grey-white mortar, the charcoal barn 20m away from the furnace and the head ironmaster’s house.

A superb cut-away image of the interior of the Dyfi Furnace, showing how all the components relate to one another, upstairs and down. The furnace is at far left with the bellows to its right and the couterwights beyond, at far right. Upstairs is the charging room where the iron ore, charcoal and limestone were poured in, and at the bottom you can see men urging the molten iron into the pig moulds in the casting house, of which only the foundations were found during excavation. The water wheel is on the other side of the far wall, powering the bellows. The chimney vents all the released gases. Source: Cadw signage at the site.

The furnace building was split into the furnace stack itself (9.1m square at the base and 8m square at the eves, and 10m tall). The furnace stack was was circular on the inside, which can be clearly seen from the ground floor. The blowing house had a vaulted brick arch (the room measuring 5.1×7.7m). The cast house measured 7.05×7.10m). There was also a counterweight room and wheel pit, together with a wheel, to operate the bellows. Two lean-to structures were added to the building, one housing the water wheel and the other apparently used for storage.

The bottom of the furnace, the bellows room and the counterweight room can all be seen from the lowest level of the site down a small flight of stairs to the right of the building as you approach from the car park.

The excavations revealed the original cast house walls, of which only 0.80cm remained. When you look in through the first arch at the furnace, you are standing where the cast house once was. Dinn says that “the variety of features in the casting area was much greater than that recorded at sites such as Bonawe and Duddon, and the casting pit much deeper, suggesting a wider range of activities than pig casting was envisaged.”

It is not known whether the bellows were leather or the more modern iron blowing tubes that were installed in at least one contemporary furnace at Duddon in Cumberland. Unfortunately there is nothing left to determine this.

The furnace, circular on the inside, but set within a square chimney, was probably composed of at least two layers of brick, separated by a fill of light rubble, earth or sand to allow for expansion of the furnace lining as it heated.

The rooms that would have contained the charging house were locked up, but this is where the iron ore (high quality Cumbrian haematite), the limestone and the charcoal would have been tipped into the furnace. A covered charging bridge also existed, leading into the charging room.

There are considerable similarties in the design to Craleckan in Argyll and Conwy in north Wales with overall similarities to both Duddon in Cumberland and Bonawe in Argyll, and it is possible that they were all designed by the same person.

Outside, the water was managed using a series of features, including at least one leat (a channel dug into the ground to direct water to where it is needed), a waterfall that was built up to give it extra power for turning the water wheel, and a tailrace to take the water away from the furnace. None of these features was excavated. The wheel and wheel pit at the site today both belong to the saw mill and are bigger than the ones for which fittings were recorded during the excavations, which were 3.60-5m, 7.5m and 7.9m diameter. The excavation report does not mention if the original water wheels used for the furnace were overshot or undershot designs.

Extensive use was made of arches throughout the building. The main components of the building are built of local shale and mortar, but some of the arches, notably the blowing arch and taphole entrance, were made of brick.

Pen and ink drawing of the Dyfi Furnace from c.1790180 by P.J. de Loutherbourg. National Library of Wales. Source: Dinn, J. 1988, p.120. The crack shown in this drawing is still clearly visible on the north wall today.

The furnace could not have operated without being able to interface with coastal carriers at Aberdovey. Cargoes destined for the Dyfi Furnace, and products produced by the furnace were carried by sea, but these ships were too large to navigate the Dovey river, so everything had to be trans-shipped via Aberdovey, which acted as an cargo handling hub between coasters and small river vessels. Materials and supplies arrived at Aberdovey by sea and were loaded onto river vessels. Pig iron manufactured at the Dyfi Furnace was in turn sent down the river to Aberdovey, where it was loaded onto seagoing ships and sent on its way. The relationship between Aberdovey and the small river ports that lined the River Dovey was completely symbiotic. Ore and ironstone shipments to the furnace are recorded from both Conwy and the River Dee, whilst the Aberdovey Custom House records shipments of iron ore from Ulverston in Cumbria. Backbarrow shipping ledgers from Ulverston record many deliveries to Dyfi Furnace.

One of the Cadw information sites at Dyfi Furnace showing coppicing and preparation of the stack for manufacturing charcoal

Information signs at the site say that the local woodlands were coppiced to make the wood go further. This simply involves cutting the wood back very close to the ground every few years so that it regrows on several new trunks from a single root. This wood was then converted to charcoal by baking it. Branches were stakced and covered with earth, and then a fire was set. Once it was burning, air was excluded from the stack and it was allowed to cook for several days. The resulting charcoal burned at higher temperatures than wood, an essential asset for charcoal blast furnaces. A single mature tree could provide sufficient fuel to manufacture two tons of iron. Records show that charcoal was also shipped into Aberdovey from Barmouth, and this is thought to be have been destined for the Dyfi furnace, to supplement its own supply. Pig iron was sent to Vernon and Kendall forges mainly in Cheshire and Staffordshire via Aberdovey but also to Barmouth. Other pig iron was sent to the local Glanfred forge on the River Leri in Ynyslas (SN643880), presumably transported by river vessel down the river Dovey and then up the Leri.

My understaning is that the furnace-master’s house has also been preserved, called Ty Furnace (translating as Furnace House), but I was unable to actually see that. It is, however, shown in both the drawings on this page.

Dovery Furnace. Etching by J.G. Wood, 1813, from his book The Principal Rivers of Wales. Source: National Library of Wales

The Dyfi Furnace was one of the last charcoal blast furnaces to be built in Britain, and is contemporary with some other well known charcoal blast furnaces including Bonawe (Argyll, Scotland), Conwy (north Wales) and Craleckan (Argyll, Scotland), all isolated areas that had good access to coastal trade routes. Richards suggests that very rural locations were selected because of their distance from Naval shipbuilding centres in the south and east of England, where shortages of shipbuilding timber were causing anxiety in the Admiralty, and competition for wood with charcoal-burning furnaces may have been suppressed.

There is very little information about the sawmill. It was probably established at Dyfi Furnace at some point between 1810 and 1887, according to Dinn, although there was a period of disused after the furnace closed, marked by the collapse of the cast house roof. A refurbishment and reorganization of the furnace building seems to have taken place a little later.

Sawmills were an innovation that simply did what the name implies. Before mechanization, sawing had been achieved by two men with a long whipsaw, one man on top of the wood being sawed, the other man below, each man pulling his end of the saw in turn. It was a highly skilled and physically demanding job, particularly for the man at the top of the saw. The sawmill replaced man power with water power. A water wheel was attached to the mechanism that did the sawing via a “pitman” (or connecting rod) that converted the circular motion of the wheel into the push-pull of the saw mechanism. How the wood was loaded and unloaded is not discussed in any of the publications that I have found to date. Given the lack of any additional structures described in the excavation reports it seems likely that loading the wood and removing it once processed were entirely manual, although mechanized systems were introduced at other sawmills. According to E.W. Cooney’s fascinating paper, although sawmills had been established much earlier in Europe, the sawmill was a relatively late phenomenon in Britain, the first ones established in the late 18th Century but not really taking off until the arrival of steam-powered sawmills in the mid 19th Century, and this appears to have been partly due to pressure from professional manual sawyers but also from doubts about the benefits of new technologies. Water power was gradually replaced by steam power, and during the 19th Century the number of water-powered sawmills declined very rapidly.

It was quite usual for a water mill that had formerly used for an entirely different task to be adapted for use as a sawmill, and often former corn mills were converted, so the re-use of a blast furnace as a sawmill was not surprising. The water wheel that remains today  is 9m (nearly 30ft) in diameter, but this may belong to a later phase than the initial conversion of the building to a saw mill and it may have been liberated from Ystrad Einion lead mine in the early 20th Century, which had a wheel of exactly the same size. It is an overshot water wheel manufactured by Williams and Metcalfe of the Rheidol Foundry, Aberystwith. The Cast House pit may have been used for tanning from the park produced at the sawmill, as happened at Bonawe. A period of disuse seems to have been followed by the demolition of the Cast House and adjacent building in around 1880, and again a sawmill appears to have been the intended use. Dinn says that it ceased to function in the 1920s.

is 9m (nearly 30ft) in diameter, but this may belong to a later phase than the initial conversion of the building to a saw mill and it may have been liberated from Ystrad Einion lead mine in the early 20th Century, which had a wheel of exactly the same size. It is an overshot water wheel manufactured by Williams and Metcalfe of the Rheidol Foundry, Aberystwith. The Cast House pit may have been used for tanning from the park produced at the sawmill, as happened at Bonawe. A period of disuse seems to have been followed by the demolition of the Cast House and adjacent building in around 1880, and again a sawmill appears to have been the intended use. Dinn says that it ceased to function in the 1920s.

The Dyfi water-powered sawmill was by now in a rather more populated area than the furnace had been. Samuel Lewis, writing in 1849, recorded that “the immediate neighborhood is well wooded and agreeable, and some respectable residences are scatted over the township,” which is “conveniently situated near smelting houses and refining mills.” He said that the river Dovey was navigable to the point where the river Einion met the Dovey for vessels up to 300 tons. Nearby Eglwysfach was a bigger settlement with an Anglican church, a Calvinist and a Wesleyan Methodist chapel and two Sunday Schools.

Dinn’s report states that the sawmill only stopped operating in around 1920, but he does not mention how it was powered at that time, and it is possible that it was still water-powered.

The main furnace buildings were adapted for uses as an agricultural store, and a flagged floor was laid down for this new role in the Blowing House. The Furnace stack was converted into a root vegetable store, with a slate floor. Subsequent use of the site was limited.

The top level at Dyfi Furnace,. The charging room where the furnace was loaded with raw materials for the transformation into pig iron.

The journey from Aberdovey to Furnace took about 30 minutes. There is a decent sized carpark to the right of the road as you head south, immediately opposite the furnace itself .

When you have parked you just need to be careful (very careful) as you cross the busy A487.

Today the site is in beautiful condition thanks to renovations in 1977-8 and again in 1984. The site is on two levels, with a set of easy steps with a handrail from one level to the other. At the top of the steps you can see the top part of the builing’s structure and take a very short walk to the waterfall.

The interior is not accessible but open grills allow you to see all you need to inside the building at ground level. The interior of the charging house at the top is closed due to horseshoe bats roosting there in the summer months. The site is free to access and there are plenty of really excellent information boards to let you know what is happening at each part of the site. On each notice board there is also a puzzle for children to explore.

Should you fancy a bit of a walk, there are a number of options that lead up the Einion valley from the waterfall, which you can find in a number of walking guides, or you can check out the ViewRanger website where there’s a short walk or a much longer one. Alternatively, if you are in the mood for a different type of experience after your visit, you might take in the bird sanctuary at Ynys Hir, a short drive away, or the nature reserve at Ynyslas, a 15 minute drive away.

If you have any more information about the site and its history, it would be great to hear from you, so please let me know.

Primary references used in this post (all references cited above and below are listed in the website Bibliography):

First, many thanks to my father, William Byrnes, for writing the section “How a Blast Furnace Works.”

Cooney, E.W. 1991. Eighteenth Century Britain’s Missing Sawmills. A Blessing in Disguise? Construction History 7, 1991, p.29-46.

https://www.arct.cam.ac.uk/Downloads/chs/vol7/article2.pdf

Daff, T. 1973. Charcoal-Fired Blast Furnaces; Construction and Operation. BIAS Journal 6

Dinn, J. 1988. Dyfi Furnace excavations 1982-1987. Post-Medieval Archaeology 22:1, p.111-142

Eyre Evans, G. 1915. The Royal Mint, Aberystwyth. Transactions of the Cardiganshire Antiquarian Society, Vol 2 No 1, (1915) p.71 http://www.ceredigionhistoricalsociety.org/trans-2-mint.php

Goodwin, G. 1894. Myddleton, Hugh. Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 39. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Myddelton,_Hugh_(DNB00)

Lewis, S. 1849. A topographical history of Wales.https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-dict/wales

Richard, A.J and Napier, J. 2005. A tale fo two rivers: Mawddach and Dyfi. Gwasg Garreg Gwalch.

Sandbach, P. 2017. Dyfi Furnace and Ystrad Einion 21st October 2016. Newsletter of the Cumbria Amenity Trust Mining History Society. February 2017, No.16,p. 17-21.

www.catmhs.org.uk/members/newsletter-126-february-2017

Walker, R.D. Iron Processing. Encylopedia Britannia. January 27, 2017 https://www.britannica.com/technology/iron-processing#ref622837

I will be talking about shipping, shipbuilders and individual ships over the next weeks and months, and in order to put these topics into context, I have been looking at how a maritime tradition developed not merely in Aberdovey but in west Wales as a whole. The following summary, amalgamating information in a number of secondary resources, is brief but hopefully provides sufficient information to introduce shipping and shipbuilding in the Aberdovey area. For those who would like to read more, I have listed the books and papers I used at the end of the post.

Mid-West Wales showing the locations of Aberdyfi (or Aberdovey), Tywyn, Borth, Machynlleth, Aberystwyth, Corris and Barmouth, key places in the story of coastal and deep sea trade and boat- and shipbuilding. Google Maps.

The 900-mile Welsh coastline, includes many river estuaries and natural harbours. Mid Wales sits within Cardigan Bay, a sweeping arc at the east of the Irish Sea, extending from the Llyn peninsula in the north to St David’s peninsula in the south. As Moelwyn Williams says: “the small ports and creeks along the coastline were focal points in the economic life of the Welsh people: they formed a kind of network of commerce and trade.” Often largely cut off from the interior due to the absence of roads, and excluded from land-based trade networks, it may have seemed inevitable that the Welsh coastal inhabitants would take to the sea, but in fact up until the 18th Century the vast majority of the ships exporting Welsh goods and supplying Welsh ports with Welsh, Irish and English goods were either English or Irish.

During the Middle Ages natural harbours became important for provisioning of military bases established by foreign invaders to fend off attempts to oust them. This means that most shipping engaged in trade at that time was not Welsh but Norman. J. Geraint Jenkins describes how wine and fruit imports could come from as far away as France and Spain, giving the example of Edward III who gave Tenby a grant to build its first landing stage in 1328, enabling it to import wine from France. Wales in return exported agricultural produce, animal hides and wool. Other traders came from nearer to home, particularly from ports along the Bristol Channel, exchanging a wide variety of imports in return for agricultural produce. An important fishing industry also developed during the Middle Ages, taking advantage of the rich herring shoals, both for local consumption and, salted, for export. The salt for preserving the herring was imported from Ireland, Cheshire and Lancashire. Irish vessels carried most of the salted fish for export, and most other ships came not from Wales but ports like Liverpool and Deeside. Piracy and smuggling were both common, with Irish salt the most commonly smuggled import due to its importance for preserving fish for export and the high duty imposed on it since 1693. Smuggling of salt only ceased when the duty was dropped in 1825.

After the conflicts of the Middle Ages a wide range of commodities and industrial products were transported along the coastline. As J. Geraint Jenkins says “Much Welsh export was transported in the veritable armada of ships owned by local people who traded the entire length of the Welsh coast.” This highlights two important points. Ships were owned by local people, sometimes by individuals who owned only one ship, usually by locals who combined their resources to purchase shares in a ship, and only more rarely by ship owners who could afford more than one ship, sometimes extending to a small fleet. The second point is that whilst much of the trade was local, in the sense that it was focused on moving commodities from one part of Wales to another, an eternal revolving door of commercial activity, some ships were also travelling regularly to Ireland and Europe, exchanging local Welsh products like wood, wool, coal, fish, wheat and beer for commodities like wine, different agricultural produce, fruit and kitchen wares.

Map of Aberdovey and its harbour in 1801. By William Morris and Lewis Morris. (National Library of Wales. Used under terms of license)

In the 18th Century, Wales was swept into the Industrial Revolution and goods like lime, coal, granite, bricks, slate, tin, lead and copper joined the export trade, and it seems to have been this that gave Welsh coastal inhabitants the impetus to take to the sea. As these new materials acquired increasing importance, so did the Welsh coastline, with investment both into improvements at existing ports, harbours and wharves and into new ports to serve specific industries. At the same time, small flat-bottomed boats continued to land on beaches to unload their cargoes, requiring no specialized facilities. Passengers, too, increasingly required transportation between commercial centres. Coastal work dominated, but long distance trade also continued to have an important role, not merely to Europe but across the Atlantic and elsewhere, facilitated by both local and foreign shipbuilders who were now building the larger ships required for such enterprises. Moelwyn Williams says that by 1768 there were around 60 ports and cargo handling creeks in Wales from Chepstow in the south to Chester in the north. In the early days of its maritime tradition, many sailors were also engaged in land-based trades, spreading the risk. By the 19th Century, however, sailors were engaged in the maritime trade full time.

The High Street of Cardigan in 1855 by Joseph Clougher (Source: National Library of Wales. Used under license)

It was only in the 19th Century that Welsh ports developed into more prosperous and organized enterprises, hubs for longer distance and sometimes international trade, building on the 18th Century trades and reinforcing it with new produce. Exports included slate, lead, copper, oak poles and planks, wooden furniture, bark, trenails (wooden pegs), butter, cheese, wheat, malt animal hides, dried salmon and wool were exported. Williams says that imports included goods from Liverpool, including bricks, tiles, boards, fir timber, potatoes, turnips and clover seeds as well as foreign commodities such as tea, sugar, tobacco, raisins, Spanish wines and spirits. Competition opened up between ports, both under sail and under steam, as trans-Atlantic trade and passenger travel took off. Steam began to make its presence felt in Wales from the first half of the 19th Century, but as Williams and Armstrong discuss, sail still dominanted for heavy cargoes, partly because steamers were most appropriate for rivers and lakes rather than the open sea, fuel costs for carrying the heavy industrial cargoes were prohibitive, and they were unsuitable for bulk cargoes due to the size of the coal bunkers that they carried. For most of the 19th Century sail and steam worked together in harmony, each suitable for different roles. Competition with the railways, spreading remorselessly into even the most remotest parts of England, Scotland and Wales, undermined coastal shipping, but provided some ship owners with the motivation to engage in more ambitious trading enterprises in the long distance deep sea trades. These ships were usually not based in Wales, and did not export Welsh goods, but many of them were owned by Welsh individuals and companies who were themselves based in Welsh villages and many were crewed by Welsh sailors. Local shipbuilders now had to compete with the Canadian counterparts for business. Many of the big ships owned in Wales were built by famous clipper and schooner shipbuilders in Canada used to designing ships that could tackle the dreadful conditions around Cape Horn. Both American and Canadian ships were larger than most British ships. In spite of the benefits of size and short-term durability, they were built of softwoods, which had a much shorter lifespan than the durable hardwoods preferred by British shipbuilders. Welsh sailors were soon to be found on ships travelling all over the world on ships that could be away from Britain for many months at a time, travelling west from ports like Liverpool, London, Bristol and Cardiff to Europe, New York, round Cape Horn to Peru and California and east as far as China, Japan and Australia. The main exports from Wales were slate and coal, with ships returning from Canada with salted dried cod for the Mediterranean, from America with copper ore, from Peru with guano, from Chile with copper ore, from the China and Japan with tea, from Australia with wool, from the Mediterranean with wine, oil, fruit, iron ore and zinc, and from eastern Europe with grain for western Europe and timber for Britain. All destined for the major British ports including Liverpool, London, Newcastle, Bristol and Cardiff. Iron ore and copper ore were of particular importance to south Wales where the tin and steel trades were developing towards the end of the 19th Century.

Cardiff from the South by Paul Sandby in 1776, showing two sloops on the River Taff (Source: MeisterDrucke https://www.meisterdrucke.uk/artist/Paul-Sandby.html