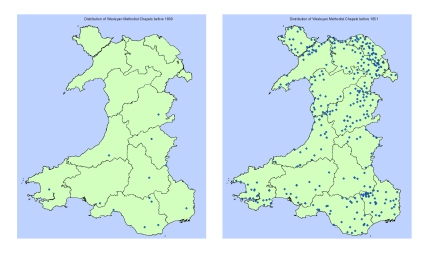

Welsh Coast Line. Source: Wikipedia, where you can see it as a single image, without rather than being split into two, as it is here.

Today the Cambrian Line runs from Shrewsbury (Shropshire) to Pwlleli (Gwynedd) with a branch just after Dovey Junction to Aberystwyth. The section from Dovey Junction (to the southwest of Derwenlas) to Pwlleli in the north is known as the Cambrian Coast Line. There are two stops in Aberdovey, one at Penhelig and the other at the far side of the village, behind the bowling club. The arrival of the railway in the 1860s had a significant impact on Aberdovey, altering the economy and physically reshaping parts of the town. The excellent legend to the left shows the final form of the railway line, complete with information about which stations remain in use. I have split it into two to fit on the page, and Morfa Mawddach appears twice as a result.

The Aberystwith and West Coast Railway was authorised by a Private Act of Parliament on 22nd July 1861. The spelling of Aberystwyth as Aberystwith was the name in which the company was registered. To put this date into perspective, by the 1860s Aberdovey had a very successful shipbuilding industry, it was an important port for the transhipping of slate exports and was important for the import of grain and other goods. Copper mines had been established in the hills around the village and a growing tourist industry based on the beach was flourishing even without a railway. There were two Nonconformist chapels dating from the late 1820s and St Peter’s Church had been established for nearly two decades.

The railway routed around the back of the village, rather than along the seafront as originally planned. Source: Hugh M. Lewis. Aberdyfi, A Glimpse of the Past.

The railway was intended to link north and mid Wales, to improve efficiencies in the export of local slate and to enable Aberdovey and Aberystwyth to serves as Irish ferry termini, linking Ireland with the Midlands. These were boom years for Aberdovey, and it must have seemed like more in the way of progress. Local people were not, however, blinded by the coming of the railway and significant disputes between Aberdovey residents, the owners of the land (the Ynynsymaengwyn Estate in Tywyn) and the representatives of the railway company over exactly where the railway should run and how the harbour would be developed. The original plan was to send the line along the sea front but extensive disputes with Aberdovey business leaders and villagers, who were concerned about the impacts on shipping, ship building and tourism, lead to it being routed around the back of the village, an expensive compromise that required tunnelling through rock. The dispute is described in Lewis Lloyd’s account on the subject in A Real Little Seaport. The need for the tunnels meant that the railway’s contractor Thomas Savin’s estimate for the cost of the railway was unrealistically low, and this contributed to his personal bankruptcy in 1866.

Thomas Savin (1826-1889) was a well known railway engineer, who built several railways in Wales. Although the contractors for the new railway are listed as Thomas and John Savin, Thomas was clearly the driving force. He had multiple business interests and often invested in his railway projects, meaning that he was far from impartial when local interests impacted business decisions, as happened in Aberdovey when villagers contested his plans to run the railway along the sea front and develop the harbour in ways that would have been harmful to local shipping and tourism interests. Savin represented the railway company in most of his dealings with the villagers. A lot more about Savin can be found on a page dedicated to him on the Llanymynech Community Project website.

Thomas Savin (1826-1889) was a well known railway engineer, who built several railways in Wales. Although the contractors for the new railway are listed as Thomas and John Savin, Thomas was clearly the driving force. He had multiple business interests and often invested in his railway projects, meaning that he was far from impartial when local interests impacted business decisions, as happened in Aberdovey when villagers contested his plans to run the railway along the sea front and develop the harbour in ways that would have been harmful to local shipping and tourism interests. Savin represented the railway company in most of his dealings with the villagers. A lot more about Savin can be found on a page dedicated to him on the Llanymynech Community Project website.

Penhelig shortly after the railway was laid, and before Penhelig Terrace was built, showing the railway tunnel and the shipyard just in front of the Penhelig Arms. Source: Hugh M. Lewis. Aberdyfi, A Glimpse of the Past.

Savin had originally intended to build a bridge across the Dyfi to connect Aberdovey and Ynyslas by rail, and this remained the plan for some time, but due to the local geomorphology, civil engineers decided that the bridge could not be built and an additional 12 miles of rail had to be laid to go around the estuary, crossing the river just north of Gogarth instead. This meant that until the new stretch was built, southbound passengers had to cross the river by ferry between Aberdovey and Ynyslas, where a line had been built. All the necessary materials for construction of the railway were carried into Aberdovey by ship, except for the locomotive and carriages that were carried from Ynyslas over the river Dyfi to Aberdovey. Aberdovey served as the depot for most of the equipment and materials, including plant, sleepers and rails. The construction work on the Aberystwith and West Coast Railway began at Aberdovey in April 1862, and was built in a number of stages,as follows:

By early September 1862 the line reached the river Dysynni and the first locomotive with 10 carriages was launched in South Merioneth and undertook the short trip from Aberdovey, stopping to pick up more passengers, to the river Dysynni and back again, carrying dignitaries and holiday makers. In the evening a firework display celebrated the achievement.

By early September 1862 the line reached the river Dysynni and the first locomotive with 10 carriages was launched in South Merioneth and undertook the short trip from Aberdovey, stopping to pick up more passengers, to the river Dysynni and back again, carrying dignitaries and holiday makers. In the evening a firework display celebrated the achievement.- In 1863 a track was laid down between Aberdovey and Llywyngwril to the north along the Welsh coast, including the three-span steel plate girder bridge over the Rivery Dysynni. This section of the line connected with the narrow gauge TalyLlyn slate quarry railway at Tywyn. Before the railway, slates were offloaded from the TalyLlyn single gauge railway, loaded on to the new line and taken to Aberdovey for loading on to ships.

- Before the section of line was built around the estuary, the s.s. Elizabeth was purchased to carry railway passengers across the river at Aberdovey to Ynyslas. The Elizabeth was a 30 horse-power Blackwall paddle steamer that was rigged for sail. She arrived in October 1863, and was captained by a Machynlleth resident Captain Edward Bell who was succeeded by his younger brother Captain John Bell. But she was not a success. At c.125ft long she was too long, and small boats had to be used to supplement the ferry service. The Elizabeth was owned by Thomas Savin, who sold it in 1869 to an agent in Londonderry.

- The section of railway between Machynlleth and Aberystwyth was completed by July 1864.

- The stretch from Aberdovey to Pwllheli was completed in August 1867, the delay caused by the building of the viaduct across the estuary at Barmouth. The line was originally intended to go along the Lleyn Peninsula to Porthdinllaen, but this plan was abandoned and the terminus was established at Pwllheli. This section of the line linked at Afonwen Junction to the Caernarfonshire Line to Caernarfon.

- In 1867 the railway was also extended along the north bank of the river to Machynlleth. The line split at Dovey Junction with two branches, one going to Machynlleth and one going to Aberystwyth.

Photograph of the Temperance Hotel in Chapel Square, showing the bridge over Copper Hill Street in the background in 1867. Source: Hugh M. Lewis. Pages of Time.

As the Newtown and Machynlleth Railway had opened at the beginning of 1863 and absorbed into Cambrian Railways the following year, the two lines were now linked. Newtown was linked to the Oswestry and Newtown Railway (which opened in 1860), which in turn linked at Welshpool to the Shrewsbury and Welshpool Railway (which opened in 1862) and the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway (opened in 1847), the Shrewsbury to Hereford line (opened in 1853) and the Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford Railway (also opened in 1853) thereby linking mid and north Wales with the borders, south Wales the Midlands.

In 1866 the line had been integrated with Cambrian Railways under the Cambrian Railways Company, which was created by an Act of Parliament in July 1864 in order to amalgamate a number of companies operating in Wales. The Aberystwith and West Coast Railway was still under construction at the time of the Act, so was not included in the original amalgamation, but was incorporated two years after the first part opened. Cambrian Railways was head-quartered at Oswestry, where there is now a heritage museum celebrating the railway, the Cambrian Railways Museum (which has a website here).

Heading to Aberdovey from Machynlleth, the line enters Aberdovey from the southeast at Penhelig Halt (added in 1933) where it emerges from a tunnel and is then carried over the road and follows a track through the back of the village before crossing the road again at the far end of Aberdovey, to continue along the coast to Tywyn. The spoil from the tunnelling operation that was required to run the railway at the back of the village was deposited in Penhelig, on land cutting into a former shipbuilding yard, and this was the site of the future Penhelig Terrace, which was built c.1865. Two tunnels were required to carry the railway through the hillside alongside the estuary, and four bridges were erected to carry it over the coast road at Penhelig, under Church Street, behind St Peter’s Church, over Copper Hill Street and at the far end of Aberdovey by the modern fire station. As soon as the line between Aberdovey and Machynlleth opened, the Corris and Aberllefenni slate carried on the Corris narrow gauge railway ceased to be loaded onto boats for transhipping onto seagoing vessels at Aberdovey, and was now transported instead by rail into Aberdovey. Much of it the Welsh Coast Railway is raised only a few feet above sea level and it follows the coastline very closely for much of its length, making it one of the most scenic coastal railways in the UK.

Aberdovey (Aberdyfi) Station was built in a location that was at that time just outside the main village. It was equipped with two platforms flanking the tracks, and a fairly substantial single-storey railway building that survives in good order, but has been converted for residential use. It is a charming red brick-built building with a slate roof, finished in stone around its doors and windows. The front of the station has decorative black engineering bricks around the porch’s archway and in a parallel linear arrangement in the walls. The porch is also equipped with twin stone columns. Penhelig Station was added in 1933, by which time the railway was operated by the Great Western Railway, which absorbed Cambrian Railways in 1922, and was equipped with a single platform and an attractive little wooden shelter that remains today.

The railway clearly improved the economic stability of Aberdovey in some ways, but it also had negative impacts. In its favour, it made it much easier for the evolving tourist industry to develop. Efficiencies in cargo handling improved, and international trade continued to be important. Cargoes that were not time sensitive still travelled by local ships, because their freight rates were so much lower, meaning that slate continued to travel by sea. However, it a number of shipbuilding yards had to be destroyed for the railway to be completed, and over the two decades after the railway arrived the shipbuilding industry went into permanent decline, aggravated by the Great Depression in Britain between 1873 and 1896). The last locally built ship was launched in 1880. Derwenlas, which was an important inland port and shipbuilding centre, was cut off from the river by the railway embankment, almost completely closing it down. Although transhipping to seagoing vessels still took place at Aberdovey for international trade, ships were no longer needed for national transportation. It was was much more efficient to carry goods and livestock by train than by boat, so the previously coastal trade faded fast. The promised Irish ferry port never arrived, and as the railways expanded and improved, minor ports lost out to big ports with better facilities and connections.

A Cambrian Railway steam engine shunting down at the modernized wharf in 1887. Source: Hugh M. Lewis. Pages of Time.

In spite of the Great Depression, the wharf and jetty were given a major overhaul in the early 1880s, and were provided with a tiny branch track that led into the wharf area and out on to the jetty. The new wharf and jetty were built on land acquired by Cambrian Railways for the purpose, opening in 1882. Two large buildings were used for the storage of cargo and building materials, the jetty was around 370ft long and allowed ships to be loaded and unloaded at both high and low tides and animal pens were erected on the foreshore to hold livestock that was offloaded from ships. Railway tracks linked the jetty and wharf to the railway so that the transhipping process was far more fluid than it ever had been before. Exports included slate from local quarries. Imports included limestone, coal and cattle from South Wales, potatoes and cattle from Ireland, grain from the Mediterranean, timber from Newfoundland, and phosphates and nitrates from South America. This will be covered in detail on a future post.

Both Penhelig and Aberdovey stations remain open today. Penhelig Station retains its 19th Century wooden shelter in an excellent state of repair, but no other station buildings. The platform is reached by a fairly long flight of steps. Aberdovey Station is at ground level, retaining the original single-storey long brick structure on the one remaining platform. It has been converted into three cottages, with the rear facing on to the platform and the front now overlooking the football pitch and adjacent to the golf cub. The short branch to the harbour that was added in the 1880s was later built over. Neither of the stations is staffed. Tickets are purchased on the train itself and there is an electronic display containing information about the next trains due to arrive. Because the platform is very low, built before platform heights were standardized, in 2009 a raised section made from reinforced glass-reinforced polymer was added. This type of solution is called a Harrington Hump after the first station to have one installed, and Aberdovey was only the third UK station to receive one, after a period of consultation with local residents. It was funded by the Welsh Government. The BBC website says that instead of the usual £250,000 to raise the level of a platform the Harrington Hump costs a mere £70,000. In 2014 part of the embankment was washed away, with the Daily Post reporting that the track was left hanging in the air. A photo gallery on the site shows repairs being carried out.

Penhelig Lodge is to the left and below the level of the railway track and the tunnel in about 1865. The photograph also shows the newly built Penhelig Terrace, which is end-on in this photograph. Source: Source: Hugh M. Lewis. Pages of Time.

The following video was shot in the 1920s and shows a steam train on the Aberdovey section of track:

Main sources:

The main source for information about the railway and its relationship to Aberdovey is Lewis Lloyd’s excellent A Real Little Seaport. The Port of Aberdyfi and its People 1565-1920. Volume 1, which makes extensive use of local newspaper reports and contemporary records. For anyone interested in learning more, there is much more information about the disputes, issues and accidents concerning the railway in his section “The Advent of the Coastal Railway” in chapter 7. Hugh M. Lewis also has some information in his book Aberdyfi – Portrait of a Village and other invaluable Hugh M. Lewis publications provide super photographic records. For more general background information two well-researched Wikipedia pages were useful sources: Aberystwith and West Coast Railway and Cambrian Railways.