Today my father and I visited the site of the Royal Silver Mint and the restored Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace at the village of Furnace (Welsh Ffwrnais), only 10km southwest of Machynlleth on the south side of the Dovey river, in Ceredigion. What an amazing place. Some of my days out have nothing much to do with Aberdovey itself, but this one is positively bristling with linkages between the 18th Century Dyfi Furnace and the contemporary port at Aberdovey.

Today my father and I visited the site of the Royal Silver Mint and the restored Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace at the village of Furnace (Welsh Ffwrnais), only 10km southwest of Machynlleth on the south side of the Dovey river, in Ceredigion. What an amazing place. Some of my days out have nothing much to do with Aberdovey itself, but this one is positively bristling with linkages between the 18th Century Dyfi Furnace and the contemporary port at Aberdovey.

Learning of the existence of the Dyfi Furnace was a complete accident. Last week my father and I drove into Aberystwyth to find out how long it would take to drive there from Aberdovey, and if there were retail facilities worth the trip. The drive was surprisingly beautiful, mainly through lovely woodland and pastures, sometimes with views over the river Dovey, the estuary and Cardigan Bay, with a spectacular descent into Aberystwyth itself, the sea a staggeringly beautiful blue. The reality of the eternally winding road meant that we were plagued with nervous and over-cautious drivers and very slow lorries, a frustrating experience behind the steering wheel. On the other hand, discovering the Dyfi Furnace was an absolutely excellent outcome of the expedition.

As we hurtled around a corner on our way to Aberystwyth, we both noticed a large water wheel on the side of an impressively solid stone-built building on the left/east of the A487, a few miles southwest of Machynlleth. When we returned from Aberystwyth I fired up my PC to find out what it was, and having identified it as Dyfi Furnace, started investigating its past. The two buildings that make up the site are managed by Cadw, and the site has a long and absolutely fascinating history dating to at least the 17th Century, spanning the reign of Charles I, the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution and the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Today it has a valuable role welcoming visitors and providing information about the area’s industrial past.

As we hurtled around a corner on our way to Aberystwyth, we both noticed a large water wheel on the side of an impressively solid stone-built building on the left/east of the A487, a few miles southwest of Machynlleth. When we returned from Aberystwyth I fired up my PC to find out what it was, and having identified it as Dyfi Furnace, started investigating its past. The two buildings that make up the site are managed by Cadw, and the site has a long and absolutely fascinating history dating to at least the 17th Century, spanning the reign of Charles I, the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution and the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Today it has a valuable role welcoming visitors and providing information about the area’s industrial past.

There is a lot to say, so this is a long post, divided up as follows:

- Introduction to the site

- Archaeology and the history of the Dyfi Furnace

- The early 17th Century lead works

- The silver mill and Royal Mint c.1648-1670

- The charcoal blast furnace c.1755-1810

- Introducing the Dfyi Charcoal Blast Furnace

- The job of a charcoal blast furnace, and how it works

- How the iron smelting process translates into furnace architecture

- The Dyfi Furnace in detail

- The sawmill c.1810/1887-1920

- The site today and visitor information

- References

All sources used throughout the post are listed at the end. You can click on images to see larger versions.

Introduction

The site is located c.10kms south of Machynlleth on what is now the A487. On the Ordnance Survey map, at SN685951 it can be found on the edge of the village of Furnace, which took its name from the Dyfi Furnace. The Dyfi Furnace is one of the last charcoal blast furnaces is to be preserved in Britain and is the best preserved in Wales. It is now managed by Cadw, Welsh Government’s historic environment service.

The site is located c.10kms south of Machynlleth on what is now the A487. On the Ordnance Survey map, at SN685951 it can be found on the edge of the village of Furnace, which took its name from the Dyfi Furnace. The Dyfi Furnace is one of the last charcoal blast furnaces is to be preserved in Britain and is the best preserved in Wales. It is now managed by Cadw, Welsh Government’s historic environment service.

The history of the Dyfi Furnace can be divided into five phases of use:

- The early 16th Century lead works

- The establishment of the Royal Silver Mills during the Civil War (1642-1651), when it shifted from Aberystwyth when Aberystwyth Castle was under threat of attack;

- Its conversion to a charcoal blast furnace in around 1755, changing hands at least twice before its closure in 1810;

- The conversion of the furnace into a sawmill

- The use of the sawmill as an agricultural storage facility, mainly for root vegetables

All three phases of use depended on water power, employing water wheels of varying sizes to transmit energy to operate machinery.

Archaeology and History

The early 17th Century lead works

In the early 17th Century, Sir Hugh Myddleton was responsible for promoting the metal mining industry in Ceredigion, with remarkable success, although he is better known for his pivotal role in the construction of the New River, to supply water from the River Lea to London. It is thought that the Ynsyhir lead smelting works, that were the first industrial works standing on the Dyfi Furnace site were part of his drive to bring industry to the area. The lead works dated from around 1620, processing lead ore to produce both lead and silver. As in later years, local wood was probably the main reason for siting the lead works in this particular place. The finished products were distributed by sea via the Dyfi estuary, helping to establish Aberdovey as an important trans-shipping port.

The Royal Silver Mint

During the reign of Charles I (1600-1649) silver coinage was produced in the Royal Mint in London from silver produced in mines throughout Britain, including Wales. The crown owned a number of silver mills in its own right, known as the Mines Royal. A paper by the Reverend Eyre Evans describes a surviving petition from 1636 that states that on the 12th May 1625 Charles I had granted one Sir Hugh Myddleton with the rights, for 31 years, to all the silver mines in the county of Cardigan, to be sent to the Royal Mint in London. By the end of 1636 silver had been sent to the Mint at a value of £50,000. The petition was sent by Thomas Bushell, member of the Society of Mines Royal, who had bought the land on Myddleton’s death from from Myddleton’s widow and hoped to retain Royal patronage for the endevour.

Threepence Charles I coins minted at Aberystwyth. Source: British Museum

Bushell was granted his petition, and now in the possession of the mines began to petition for a mint (a coin factory) in Aberystwyth Castle to manufacture coins exclusively from Welsh silver mines, citing the precedent of Ireland, where a Royal Mint had been established. Rather surprisingly, given strongly worded objections from the Royal Mint in London, on the 9th July 1637 Bushell was again granted his wish, and was authorized to coin the half-crown, shilling, half-shilling, two-pence, and penny, all from Welsh silver. In October of the same year the groat, threepence and half-penny were added to the list. A set of accounts for the Aberystwyth Castle mint last up until 1642, when they cease abruptly, almost certainly due to the outbreak of the Civil War and the threat to the mint from Parliamentarian forces, and the castle was actually occupied briefly in 1648.

Tentative suggestions that during the Civil War (1642-1651) the Aberystwyth Royal Mint was moved to the site at Furnace were unambiguously confirmed during the 1986 excavations by James Dinn and his team, a great result. Ceredigion silver was very highly valued and moving the Royal Mint to this location was a sound plan, particularly as Charles I was in urgent need of coin to pay his army. This seems to have taken place in 1648 or a short time beforehand.

The silver mill had been described by Sir John Pettus and John Ray in 1670 and 1674 respectively, and a plan by Waller (1704) survives. These between them describe furnaces, possibly up to five of them, the mint house and the stamping mill surrounding a courtyard, together with the mint house, a lead mill and a refining house. Between them the buildings had four water wheels to operate four sets of bellows. One of the wheel pits was found during the excavations. A cobbled surface was also found during excavations, apparently belonging to the courtyard of the silver mill.

Dinn says that the dates during which the silver mill was in use are uncertain, but that it may have operated in 1645-6 and 1648-9. Activity was apparently suspended in 1650 but the works seem to have been in operation again in 1650. 1670 seems to mark the date for its permanent abandonment.

The Charcoal Blast Furnace

Introducing the Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace

At the top of the Dyfi Furnace, the charging room, from where the furnace was fed.

The Dyfi Charcoal Blast Furnace was built in c.1755 and was in use for five years for iron smelting (the production of iron from natural iron ore). The excavations found that later conversion to a sawmill had destroyed some of the blast furnace components but preserved others. Charcoal blast furnaces had been introduced into Britain in the late 15th Century but it took another century for them to become widespread.

The furnace was initially leased in c.1755 from Lewis and Humphrey Edwards by Ralph Vernon together with the brothers Edward and William Bridge, who had been involved with the building of a furnace in Conwy, north Wales in 1750. The furnace-master, who was accommodated in a house at the site called Ty Furnace, was Thomas Gaskell. Vernon retired sometime between 1765 and 1770 and the Bridge brothers went bankrupt in 1773. Dinn says that this “left members of the Kendall family in sole control of Conwyy and Dyfi furnaces.” I am not clear on how the Kendalls, west Midlands iron-masters with interests throughout Britain, came to be in control, but the Kendalls may have invested in the furnace operation. Ralph Vernon was a cousin of Jonathan and Henry Kendall and they had been in business together before. Both Dyfi and Conwy furnaces were put up for sale in 1774. No buyers were found and it is thought that John Kendall probably managed the Dyfi furnace himself until his death in 1791, but the Conwy furnace closed in around 1779. In 1796 the lease again changed hands and was now in the name of Messrs Bell and Gaskell, the latter being the Thomas Gaskell who had been the furnace master at Dyfi Furnace under the Kendalls. Dyfi Furnace went out of use as an iron ore smelting furnace in around 1810.

There were four reasons for basing the furnace at the foot of the River Einion waterfall.

There were four reasons for basing the furnace at the foot of the River Einion waterfall.

- First, the waterfall provided power for the water wheel, and with its source high in the hills, originating in Craiglin Dyffi near the summit of the remote Aran Faddwy, the tallest peak in the area, it was unlikely to dry up at any part of the year. The water wheel powered the bellows that gave the blast furnace its name.

- Second, there was a road to the river village of Garreg, 2km away, that provided access to the navigable part of the River Dovey (Afon Dyfi), which provided easy access to the sea port of Aberdovey. The furnace depended upon Aberdovey for transfer of iron ore (the natural material from which iron is extracted in the furnace) from Cumbria to river ships that could make the trip to Garreg, and for transhipping its pig iron (iron produced from iron ore that was now in a state ready to be worked in a forge by a blacksmith) to elsewhere in the country.

- Third, it was surrounded by rich woodland that was exploited for the manufacture of charcoal to fuel the furnace.

- Finally, it was immediately next to the turnpike road out of Machynlleth, providing access to the market town.

Both iron ore and limestone had to be imported. The iron ore came mainly from Cumbria, but it is not clear where the limestone was sourced. Limestone is available in north Wales, and there are records of imports to the furnace from the River Dee, so this is a plausible source.

The entire complex included the Furnace (blast furnace stack, the hearth at its base, a casting house, a bellows room, a counterweight room, a charging room), an external charcoal storage building and the iron-master’s house, Ty Furnace.

Plan of the buildings associated with the Dyfi Furnace. Source: Dinn, J. 1988, p.112

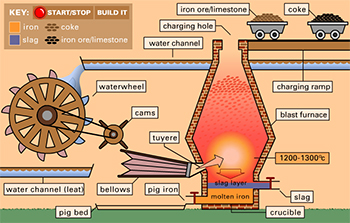

The job of the charcoal blast furnace, and how it works

Iron Smelting

A furnace is an impressive combination of chemical and mechanical engineering.

Iron ores are a mixture of oxides and sulphates of iron, predominantly haematite, ferric oxide (Fe2O3). However, the haematite and other iron oxides come mixed with a variety of other minerals, containing such elements as silica, alumina, phosphorous, manganese and sulphur. The smelting process must accomplish two things.

It must split the molecules of the iron compounds so that the iron is separated from the oxygen. This is done by the addition of heat and the supply of carbon in the form of (in this case) charcoal. In this chemical and physical environment, the addition of heat energy divides the ore into iron and carbon dioxide, CO2. The hot carbon dioxide exits through the chimney. Notice that the charcoal is both the source of heat, and a chemical reagent combining with the oxygen in the ferric oxide.

The second thing the process must accomplish is remove the other minerals that accompany the haematite in the iron ore. This is achieved in two ways. First, the addition of intense heat acts in much the same way as it does with the haematite taking off some of the impurities as gases. However, it also requires the addition of a limestone (primarily composed of calcite, CACO3) “flux,” which both lowers the melting point of the mixture and bonds with the impurities to make a silicaceous liquid, physically and chemically similar to a very impure glass. Being silicaceous, it is light and floats on the iron, making it relatively easy to separate.

The addition of oxygen

Oxygen is added by use of bellows. There are two features of the flow of air in a furnace which are worth noting. First the bellows are much more effective blowing into a confined space. Blowing into an open hearth, the air is quickly dissipated, as is the heat produced. Second, the narrow funnel at the top of the furnace creates what engineers call a “venturi.” It forces the hot rising gases into a much smaller space so that their speed increases, in the same way that like the narrowing of the nozzle size on a hose pipe, increases the speed at which the water squirts out. When the velocity of a gas increases, its pressure falls, according to a physical law known as Bernoulli’s principle. The low pressure at the top of the furnace pulls the air through the smelting mixture just as the air from the bellows is pushing it. Together, they increase the amount of oxygen from the air which reaches the burning charcoal, radically increasing its temperature.

Bellows

Bellows are a device for taking a lot of air from an unconfined place and pushing it at high pressure into a smaller place. To operate successfully the bellows need four features.

First, and most obvious, a bag into which the air can be sucked from the atmosphere. At this time the bag were usually leather.

The second thing that the bellows need are a way of opening and closing the bag. In this furnace opening is achieved by a cog with one side of each tooth rounded (see diagram), driven by a water wheel. The opening is achieved by a counter weight connected to a lever which is pulled up by the same cog mechanism (see diagram). When the tooth of the cog passes, the counterweight falls to open the bellows.

The third thing is a valve on the leather bag which lets air be sucked in when the bellow are open, but not blown out when they are closing.

Finally, the bellows need a narrow nozzle to push the air at high speed into the furnace chamber to deliver oxygen to the charcoal and increase the rate of combustion.

A Cadw sign from the site showing how the counterweights related to the functionality of the bellows

How the iron smelting process translates into furnace architecture

The furnace consists of a number of different rooms, each devoted to a different task:

- The charge (charcoal, limestone flux and iron ore) is fed in from the charging room at the top of the furnace. This room keeps the charcoal dry whilst it is being fed into the furnace.

- The furnace itself is in a square stack, but is circular in form. A small round opening at the top (the neck) flares out down the length of the stack to allow the materials to expand as they are heated from a blast from the bellows. The stack suddenly narrows into a funnel, called the bosh. Finally, the a tall cylinder at the base, the hearth, is where the molten iron and slag gathers.

- The heat within the furnace is maintained by the bellows, which are contained within the bellows room and these are operated by a water wheel on the outside of the building.

- A counterweight room contains the counterweights that raise and drop the bellows. The bellows connect to the furnace via an pipe, c.3 inches in diameter, and a nozzle called a tuyère that are carried through a tuyère hole or blasting arch at about 1ft above the base of the furnace at the correct angle to give maximum impact.

- The area in the hearth below the tuyère where the liquid metal comes to rest is called the crucible.

- Molten slag, floating on top, and molten iron, below, pass through separate tapholes. The iron passes through an arch, called a casting arch, into the the casting room. This is where the iron hardens in clean and dry conditions.

Looking in detail at the Dyfi Furnace

When it was built in c.1755 the Dyfi Furnace appears to have consisted of a free-standing blast furnace, with other components added a little later. The completed complex consisted of the furnace building made of local shale from the Silurian period Llandovery series and grey-white mortar, the charcoal barn 20m away from the furnace and the head ironmaster’s house.

A superb cut-away image of the interior of the Dyfi Furnace, showing how all the components relate to one another, upstairs and down. The furnace is at far left with the bellows to its right and the couterwights beyond, at far right. Upstairs is the charging room where the iron ore, charcoal and limestone were poured in, and at the bottom you can see men urging the molten iron into the pig moulds in the casting house, of which only the foundations were found during excavation. The water wheel is on the other side of the far wall, powering the bellows. The chimney vents all the released gases. Source: Cadw signage at the site.

The charcoal store

The furnace building was split into the furnace stack itself (9.1m square at the base and 8m square at the eves, and 10m tall). The furnace stack was was circular on the inside, which can be clearly seen from the ground floor. The blowing house had a vaulted brick arch (the room measuring 5.1×7.7m). The cast house measured 7.05×7.10m). There was also a counterweight room and wheel pit, together with a wheel, to operate the bellows. Two lean-to structures were added to the building, one housing the water wheel and the other apparently used for storage.

Site plan from the excavation report. Source: Dinn, J. 1988, page 122

The bottom of the furnace, the bellows room and the counterweight room can all be seen from the lowest level of the site down a small flight of stairs to the right of the building as you approach from the car park.

The excavations revealed the original cast house walls, of which only 0.80cm remained. When you look in through the first arch at the furnace, you are standing where the cast house once was. Dinn says that “the variety of features in the casting area was much greater than that recorded at sites such as Bonawe and Duddon, and the casting pit much deeper, suggesting a wider range of activities than pig casting was envisaged.”

It is not known whether the bellows were leather or the more modern iron blowing tubes that were installed in at least one contemporary furnace at Duddon in Cumberland. Unfortunately there is nothing left to determine this.

The interior, circular design of the furnace.

The furnace, circular on the inside, but set within a square chimney, was probably composed of at least two layers of brick, separated by a fill of light rubble, earth or sand to allow for expansion of the furnace lining as it heated.

The rooms that would have contained the charging house were locked up, but this is where the iron ore (high quality Cumbrian haematite), the limestone and the charcoal would have been tipped into the furnace. A covered charging bridge also existed, leading into the charging room.

There are considerable similarties in the design to Craleckan in Argyll and Conwy in north Wales with overall similarities to both Duddon in Cumberland and Bonawe in Argyll, and it is possible that they were all designed by the same person.

Outside, the water was managed using a series of features, including at least one leat (a channel dug into the ground to direct water to where it is needed), a waterfall that was built up to give it extra power for turning the water wheel, and a tailrace to take the water away from the furnace. None of these features was excavated. The wheel and wheel pit at the site today both belong to the saw mill and are bigger than the ones for which fittings were recorded during the excavations, which were 3.60-5m, 7.5m and 7.9m diameter. The excavation report does not mention if the original water wheels used for the furnace were overshot or undershot designs.

Extensive use was made of arches throughout the building. The main components of the building are built of local shale and mortar, but some of the arches, notably the blowing arch and taphole entrance, were made of brick.

Pen and ink drawing of the Dyfi Furnace from c.1790180 by P.J. de Loutherbourg. National Library of Wales. Source: Dinn, J. 1988, p.120. The crack shown in this drawing is still clearly visible on the north wall today.

The furnace could not have operated without being able to interface with coastal carriers at Aberdovey. Cargoes destined for the Dyfi Furnace, and products produced by the furnace were carried by sea, but these ships were too large to navigate the Dovey river, so everything had to be trans-shipped via Aberdovey, which acted as an cargo handling hub between coasters and small river vessels. Materials and supplies arrived at Aberdovey by sea and were loaded onto river vessels. Pig iron manufactured at the Dyfi Furnace was in turn sent down the river to Aberdovey, where it was loaded onto seagoing ships and sent on its way. The relationship between Aberdovey and the small river ports that lined the River Dovey was completely symbiotic. Ore and ironstone shipments to the furnace are recorded from both Conwy and the River Dee, whilst the Aberdovey Custom House records shipments of iron ore from Ulverston in Cumbria. Backbarrow shipping ledgers from Ulverston record many deliveries to Dyfi Furnace.

One of the Cadw information sites at Dyfi Furnace showing coppicing and preparation of the stack for manufacturing charcoal

Information signs at the site say that the local woodlands were coppiced to make the wood go further. This simply involves cutting the wood back very close to the ground every few years so that it regrows on several new trunks from a single root. This wood was then converted to charcoal by baking it. Branches were stakced and covered with earth, and then a fire was set. Once it was burning, air was excluded from the stack and it was allowed to cook for several days. The resulting charcoal burned at higher temperatures than wood, an essential asset for charcoal blast furnaces. A single mature tree could provide sufficient fuel to manufacture two tons of iron. Records show that charcoal was also shipped into Aberdovey from Barmouth, and this is thought to be have been destined for the Dyfi furnace, to supplement its own supply. Pig iron was sent to Vernon and Kendall forges mainly in Cheshire and Staffordshire via Aberdovey but also to Barmouth. Other pig iron was sent to the local Glanfred forge on the River Leri in Ynyslas (SN643880), presumably transported by river vessel down the river Dovey and then up the Leri.

My understaning is that the furnace-master’s house has also been preserved, called Ty Furnace (translating as Furnace House), but I was unable to actually see that. It is, however, shown in both the drawings on this page.

Dovery Furnace. Etching by J.G. Wood, 1813, from his book The Principal Rivers of Wales. Source: National Library of Wales

The Dyfi Furnace was one of the last charcoal blast furnaces to be built in Britain, and is contemporary with some other well known charcoal blast furnaces including Bonawe (Argyll, Scotland), Conwy (north Wales) and Craleckan (Argyll, Scotland), all isolated areas that had good access to coastal trade routes. Richards suggests that very rural locations were selected because of their distance from Naval shipbuilding centres in the south and east of England, where shortages of shipbuilding timber were causing anxiety in the Admiralty, and competition for wood with charcoal-burning furnaces may have been suppressed.

Saw Mill

There is very little information about the sawmill. It was probably established at Dyfi Furnace at some point between 1810 and 1887, according to Dinn, although there was a period of disused after the furnace closed, marked by the collapse of the cast house roof. A refurbishment and reorganization of the furnace building seems to have taken place a little later.

An early sawmill showing two men creating planks with a straight whipsaw. Source: Cooney 1991

Sawmills were an innovation that simply did what the name implies. Before mechanization, sawing had been achieved by two men with a long whipsaw, one man on top of the wood being sawed, the other man below, each man pulling his end of the saw in turn. It was a highly skilled and physically demanding job, particularly for the man at the top of the saw. The sawmill replaced man power with water power. A water wheel was attached to the mechanism that did the sawing via a “pitman” (or connecting rod) that converted the circular motion of the wheel into the push-pull of the saw mechanism. How the wood was loaded and unloaded is not discussed in any of the publications that I have found to date. Given the lack of any additional structures described in the excavation reports it seems likely that loading the wood and removing it once processed were entirely manual, although mechanized systems were introduced at other sawmills. According to E.W. Cooney’s fascinating paper, although sawmills had been established much earlier in Europe, the sawmill was a relatively late phenomenon in Britain, the first ones established in the late 18th Century but not really taking off until the arrival of steam-powered sawmills in the mid 19th Century, and this appears to have been partly due to pressure from professional manual sawyers but also from doubts about the benefits of new technologies. Water power was gradually replaced by steam power, and during the 19th Century the number of water-powered sawmills declined very rapidly.

It was quite usual for a water mill that had formerly used for an entirely different task to be adapted for use as a sawmill, and often former corn mills were converted, so the re-use of a blast furnace as a sawmill was not surprising. The water wheel that remains today  is 9m (nearly 30ft) in diameter, but this may belong to a later phase than the initial conversion of the building to a saw mill and it may have been liberated from Ystrad Einion lead mine in the early 20th Century, which had a wheel of exactly the same size. It is an overshot water wheel manufactured by Williams and Metcalfe of the Rheidol Foundry, Aberystwith. The Cast House pit may have been used for tanning from the park produced at the sawmill, as happened at Bonawe. A period of disuse seems to have been followed by the demolition of the Cast House and adjacent building in around 1880, and again a sawmill appears to have been the intended use. Dinn says that it ceased to function in the 1920s.

is 9m (nearly 30ft) in diameter, but this may belong to a later phase than the initial conversion of the building to a saw mill and it may have been liberated from Ystrad Einion lead mine in the early 20th Century, which had a wheel of exactly the same size. It is an overshot water wheel manufactured by Williams and Metcalfe of the Rheidol Foundry, Aberystwith. The Cast House pit may have been used for tanning from the park produced at the sawmill, as happened at Bonawe. A period of disuse seems to have been followed by the demolition of the Cast House and adjacent building in around 1880, and again a sawmill appears to have been the intended use. Dinn says that it ceased to function in the 1920s.

The Dyfi water-powered sawmill was by now in a rather more populated area than the furnace had been. Samuel Lewis, writing in 1849, recorded that “the immediate neighborhood is well wooded and agreeable, and some respectable residences are scatted over the township,” which is “conveniently situated near smelting houses and refining mills.” He said that the river Dovey was navigable to the point where the river Einion met the Dovey for vessels up to 300 tons. Nearby Eglwysfach was a bigger settlement with an Anglican church, a Calvinist and a Wesleyan Methodist chapel and two Sunday Schools.

Dinn’s report states that the sawmill only stopped operating in around 1920, but he does not mention how it was powered at that time, and it is possible that it was still water-powered.

After the Sawmill

The main furnace buildings were adapted for uses as an agricultural store, and a flagged floor was laid down for this new role in the Blowing House. The Furnace stack was converted into a root vegetable store, with a slate floor. Subsequent use of the site was limited.

The Site today and visitor Information

The top level at Dyfi Furnace,. The charging room where the furnace was loaded with raw materials for the transformation into pig iron.

The journey from Aberdovey to Furnace took about 30 minutes. There is a decent sized carpark to the right of the road as you head south, immediately opposite the furnace itself .

When you have parked you just need to be careful (very careful) as you cross the busy A487.

Today the site is in beautiful condition thanks to renovations in 1977-8 and again in 1984. The site is on two levels, with a set of easy steps with a handrail from one level to the other. At the top of the steps you can see the top part of the builing’s structure and take a very short walk to the waterfall.

The interior is not accessible but open grills allow you to see all you need to inside the building at ground level. The interior of the charging house at the top is closed due to horseshoe bats roosting there in the summer months. The site is free to access and there are plenty of really excellent information boards to let you know what is happening at each part of the site. On each notice board there is also a puzzle for children to explore.

Should you fancy a bit of a walk, there are a number of options that lead up the Einion valley from the waterfall, which you can find in a number of walking guides, or you can check out the ViewRanger website where there’s a short walk or a much longer one. Alternatively, if you are in the mood for a different type of experience after your visit, you might take in the bird sanctuary at Ynys Hir, a short drive away, or the nature reserve at Ynyslas, a 15 minute drive away.

If you have any more information about the site and its history, it would be great to hear from you, so please let me know.

References

Primary references used in this post (all references cited above and below are listed in the website Bibliography):

First, many thanks to my father, William Byrnes, for writing the section “How a Blast Furnace Works.”

Cooney, E.W. 1991. Eighteenth Century Britain’s Missing Sawmills. A Blessing in Disguise? Construction History 7, 1991, p.29-46.

https://www.arct.cam.ac.uk/Downloads/chs/vol7/article2.pdf

Daff, T. 1973. Charcoal-Fired Blast Furnaces; Construction and Operation. BIAS Journal 6

Dinn, J. 1988. Dyfi Furnace excavations 1982-1987. Post-Medieval Archaeology 22:1, p.111-142

Eyre Evans, G. 1915. The Royal Mint, Aberystwyth. Transactions of the Cardiganshire Antiquarian Society, Vol 2 No 1, (1915) p.71 http://www.ceredigionhistoricalsociety.org/trans-2-mint.php

Goodwin, G. 1894. Myddleton, Hugh. Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 39. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Myddelton,_Hugh_(DNB00)

Lewis, S. 1849. A topographical history of Wales.https://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-dict/wales

Richard, A.J and Napier, J. 2005. A tale fo two rivers: Mawddach and Dyfi. Gwasg Garreg Gwalch.

Sandbach, P. 2017. Dyfi Furnace and Ystrad Einion 21st October 2016. Newsletter of the Cumbria Amenity Trust Mining History Society. February 2017, No.16,p. 17-21.

www.catmhs.org.uk/members/newsletter-126-february-2017

Walker, R.D. Iron Processing. Encylopedia Britannia. January 27, 2017 https://www.britannica.com/technology/iron-processing#ref622837

Walking towards Tywyn from Aberdovey you will come across a Second World War pillbox, an ugly concrete box with a small square hole in each side. It has subsided unevenly into a dip in the beach at the foot of the dunes, an incongruous contributor to the area’s heritage. It can be reached easily along the beach from Aberdovey. It’s a fairly short walk from the car park, a little way beyond the Trefeddian Hotel, which is visible through a dip in the sand dunes. If you prefer a short-cut there is a public footpath from a big lay-by on the A493 that takes you across the sand dunes and drops you very close to it. Not that it’s a tourist destination, but it is certainly a local landmark, and sitting in an unspoiled stretch of eternal pale yellow sands with the rich blue sea beyond, it has an emphatic presence all of its own. It is at grid reference SN59549635, at the end of the footpath known as The Crossing.

Walking towards Tywyn from Aberdovey you will come across a Second World War pillbox, an ugly concrete box with a small square hole in each side. It has subsided unevenly into a dip in the beach at the foot of the dunes, an incongruous contributor to the area’s heritage. It can be reached easily along the beach from Aberdovey. It’s a fairly short walk from the car park, a little way beyond the Trefeddian Hotel, which is visible through a dip in the sand dunes. If you prefer a short-cut there is a public footpath from a big lay-by on the A493 that takes you across the sand dunes and drops you very close to it. Not that it’s a tourist destination, but it is certainly a local landmark, and sitting in an unspoiled stretch of eternal pale yellow sands with the rich blue sea beyond, it has an emphatic presence all of its own. It is at grid reference SN59549635, at the end of the footpath known as The Crossing.

Pillboxes were part of a network of small defences that were put in place along the coastline, at road junctions and on canals to counter threats of Nazi attack on Britain. The network consisted of a number of measures including offshore minefields; beach and manned seafront obstacles like barbed wire and landing craft obstructions, pillboxes and minefields; and cliff-top and dune defences including pillboxes and anti-glider obstructions. The pillboxes, 28,000 of them, were sometimes round or hexagonal to avoid blind spots, but there were were seven different types in total (Types 22-28), with variants. The Aberdovey one is a Type 26 prefabricated square with an embrasure in each wall and a door, now slightly subsided into a slight dip in the sand, 3ft or so deep. Some pillboxes were brick- or stone-built but many, like this one, were made of concrete that was sufficiently thick to be bullet proof. My thanks to the Pillbox Study Group for this excerpt, which explains the thinking behind pillboxes and other defence structures that were put in place in WWII:

Pillboxes were part of a network of small defences that were put in place along the coastline, at road junctions and on canals to counter threats of Nazi attack on Britain. The network consisted of a number of measures including offshore minefields; beach and manned seafront obstacles like barbed wire and landing craft obstructions, pillboxes and minefields; and cliff-top and dune defences including pillboxes and anti-glider obstructions. The pillboxes, 28,000 of them, were sometimes round or hexagonal to avoid blind spots, but there were were seven different types in total (Types 22-28), with variants. The Aberdovey one is a Type 26 prefabricated square with an embrasure in each wall and a door, now slightly subsided into a slight dip in the sand, 3ft or so deep. Some pillboxes were brick- or stone-built but many, like this one, were made of concrete that was sufficiently thick to be bullet proof. My thanks to the Pillbox Study Group for this excerpt, which explains the thinking behind pillboxes and other defence structures that were put in place in WWII: